Exploring the ‘George Finlay table’

Esther Laver (University of Cambridge) volunteered for the BSA on our 2020 ‘Digitisation Project’, helping to inventory the collection. Here, she revisits the experience of opening up the ‘George Finlay table’ and cataloguing its contents for the very first time.

When I first came to the BSA as a student on the undergraduate course in 2019, I knew little of Finlay, prehistory, and the BSA’s collections. To me, ‘Finlay’ was a part of the furniture, one minutia out of the many which filled those three weeks; ‘prehistory’ was Schliemann and Mycenae; the history of the BSA was irrelevant to me. In 2020, the BSA’s Digitisation Project allowed me to tackle all these features of the BSA’s past, present, and future.

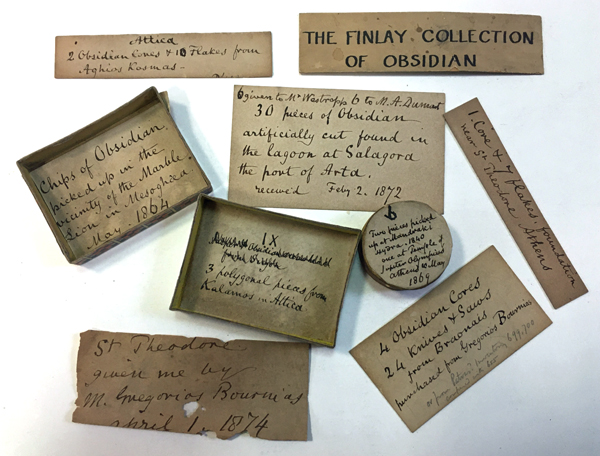

I spent my September as a volunteer at the BSA, working on the Digitisation Project – an undertaking long overdue to fully inventory and photograph all objects in the BSA collections, and one I am immensely proud and grateful to have been a part of. My first task was to catalogue a portion of the Lithics collection: the Finlay Cabinet, hidden away in a corner of the Museum during my previous visit. The Finlay Cabinet held its namesake’s collection of obsidian: hundreds of cores, blades, fragments, and flakes in four drawers, with a messy myriad labels. Like other parts of his collections which had found their way to the BSA, the obsidian collection corresponded to Finlay’s original catalogue (FIN/C.15).

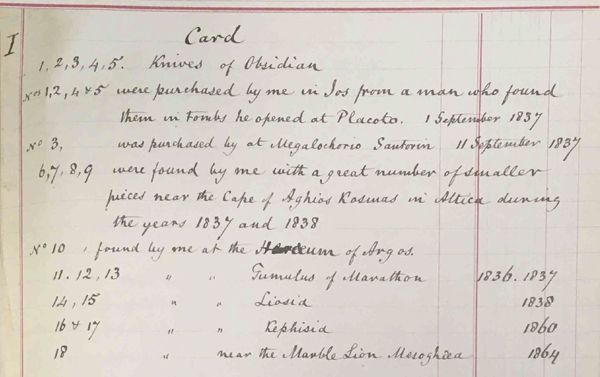

FIN/C.15, Card I: List of obsidian stone tools collected by George Finlay correspond to obsidian pieces mounted onto a piece of cardboard as a reference sheet.

Finlay died in 1875, eleven years before the BSA was founded. He had come to Greece in 1823 for the War of Independence, and afterwards settled in Athens. He travelled: around Greece, further abroad, and back to his native Scotland. He wrote a history of Greece up until his own time – A History of Greece: From Its Conquest by the Romans to the Present Time, BC 146 to AD 1864 – and was preoccupied with the society and politics of the incipient republic. After his death, his collections and papers were donated to various institutions – including the BSA, in 1899.

Finlay’s labels for his obsidian, still happily resident in the Cabinet, gave varying levels of detail on where, when, and how he had come into possession of the material: for instance, purchased from a man named Gregorios Bournias in Athens (MUS.L355-7), or found at the ‘tumulus’ at Marathon (MUS.L362-7). The labels spelled out Finlay’s travels, from Athens in 1869 to the Argive Heraion in 1832 to Corinth in 1872; even without his original catalogue or consulting Finlay’s own papers and books, I could trace the journeys of a man I knew little about. These pieces of rock were not only archaeological material, indicators of life and living; they were also the archaeological material of this man’s life: a snapshot of his travels in and around Greece, a glimpse into the mores of society under the new King Otto, and the fragmented beginnings of prehistoric archaeology.

The Finlay Cabinet introduced me to the Museum and the Digitisation Project. When it had been catalogued, an out-of-focus image of Finlay and the BSA began to come into view. Through the Project, we were building a history of the BSA through its collections, at the same time as preserving those collections, and making them accessible. Finlay was only a part of this – a part that had begun before the BSA itself. I next turned to the Finlay Table.

The Finlay Table brought the image of Finlay and the BSA further into focus. Half of the drawers in the Table had already been catalogued; the remaining five were an assortment of impressions, lithics, antlers, and a box of “charred food”. Not everything in this eclectic assemblage had been collected by Finlay; many of their labels had been written by others, such as Walter Heurtley, who had been assistant director of the BSA in 1923-1933.

Between Cabinet and Table, I had spent a couple of days cataloguing another drawer of the Lithics collection. The many hands of the labels there had perplexed and frustrated me; eventually, it transpired that Heurtley had ‘catalogued’ those lithics himself during his tenure: labels which initially appeared to have been signed by multiple people in the same hand were actually Heurtley’s own records of how, when, and from whom objects came into the BSA’s collections. Previous attempts to catalogue overlapped and interfered and ran together, each building on others as the collections grew and expanded, almost out of control.

Different people left things in the Table; they were from different places, too. (Almost) everything I had already catalogued in the Finlay Cabinet was from Greece. The Finlay Table, however, also held sherds, flint, blades, and bone which Finlay had collected from Switzerland. Finlay’s travels and writings had taken him to Switzerland, though most of the material I had dealt with was from Greece. Between his writings and the foreign objects before me, an ulterior motive and secondary dimension to Finlay’s collections began to emerge.

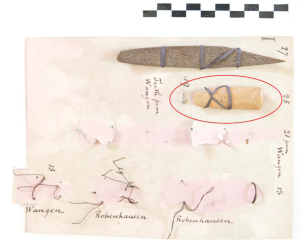

MUS.M136. Model of a lake village wooden handle to hold stone tool with antler haft.

In the final drawer (which also happened to hold two antlers) were three ceramic sherds (MUS.A729-31), collected in 1868, and accompanied by two of Finlay’s labels: “Pottery of – stone period – fished up with – Dr Keller – 7 aug 1868”; “Pottery of – Bronze period – fished up by Dr Keller – in my presence, Zurich – 8 aug 1868”. These labels corresponded to a contemporary eruption in interest in Greek prehistory, and an age before Homer and the Classical; the late 1860s, a time before Schliemann and Mycenae, Evans and Knossos, were preoccupied with the “three-age system” and “pre-Hellenic” civilisations. The array of obsidian and ancient memorabilia in Finlay’s collections were the products of his own search for a Greece pre-history. With the Table labels, we could pinpoint Finlay’s interests and research actualising before him – yet not in Greece, but in Switzerland!

For most, the Late Bronze Age palaces are their introduction to prehistory; for some, if they know anything about prehistory, it is only the palaces. But before that discovery came an older pursuit: for lake-dwellers, stone tools, a stone age. As the search for deep history began and gained momentum, the nineteenth century saw the formation and development of related disciplines, particularly palaeontology and geology. In European archaeology, Finlay and others made increasingly greater strides towards uncovering the pre-Bronze Age prehistoric past of Greece and wider Europe through their interests in and investigations of fossils and stone tools. In 1869, Finlay himself published a pamphlet in Greek entitled Observations on Prehistoric Archaeology in Switzerland and Greece, the original manuscript of which is in the BSA’s archive. In the 1870s, however, in the wake of Schliemann and Mycenae, international and academic curiosity turned elsewhere. It was not to be revisited until the mid-twentieth century; alongside this renewed interest in the Stone Age, Finlay’s work in the field of prehistory in its infancy has more recently begun to be given due recognition.

MUS.L523. Stone tooth attached to a piece of cardboard with brown ribbon along with six other pieces, five of which are missing. This piece is labelled “25” near a label “Teeth from Wangen” by Finlay in handwritten notes on the cardboard. “25” is also written by Finlay directly onto the piece in black ink. A light brown colour. Smooth surfaces and edges. Discolouration beneath the ribbon holding it to the cardboard.

Finlay’s collections at the BSA are proof of one unfulfilled trajectory of archaeology in Greece. Once catalogued and digitised, they can tell the story of his travels, his thoughts, and the times in which he lived; they widen our grasp of the emerging study of Greek and European prehistory. They form only a small part of the BSA’s vast collections, with many more stories to be told. The collections did not begin or end with Finlay, or with Heurtley, or with those of us who worked on the Digitisation Project; they continued and continue and find their roots in antiquity and today, in our research and reconstructions and confrontations with the many pasts of Greece.

Esther Laver

BSA Digitisation Project, August / September 2020

University of Cambridge