Shooting the Past: Making Connections in the BSA Photographic Archives

Stephen Poliakoff’s 1999 TV drama, Shooting the Past tells a story of an extraordinary photographic library whose goal is to preserve the past through its vast archive. The library holds over ten million photographs, categorised in numerous collections. Crisis comes when an American company buys the building which houses the enormous library. The company intends to destroy most of the photographs and split up the remainder. To save their library, the eccentric staff of curators attempt to persuade the company of the value of keeping the library intact by researching and telling life stories of ordinary people stitched together from photographs across multiple collections using the entire library. Their ploy doesn’t work out exactly as planned and I won’t spoil the ending of the story by telling you what happened. The main point, for me, was the method of how the photographic curators compiled their stories of people’s pasts by finding connections across disparate collections.

Finding connections across collections is something I’ve encountered in the BSA photographic archive. The story starts with a collection that I have been working on for many years – the old photographic collection of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS). This collection was assembled from the last two decades of the 19th century until the middle of the 20th from donations of negatives and prints by members, scholars and travellers to Hellenic lands. In fact, one of the Hellenic Society’s original mandates when it formed in 1879 was to collect visual material – drawings, facsimiles, plans and photographs – to create a reference collection. Ultimately, in 1892 a lending library of lantern slides (duplicated from the negatives) was formed. The Society also began selling duplicate slides and prints to members and other institutions. Part of this negative and slide collection came to the BSA in 2003 and I resumed studying it here in 2015. The remainder of the SPHS collection went to the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archives (since 2009 part of the National Bank of Greece’s Cultural Foundation, MIET-ELIA) in 2003.

The SPHS images that came to the BSA were selected by identifying donors who had connections with the BSA and images of topographical interest, particularly in areas where the BSA was known to have explored. The BSA-SPHS collection now contains approximately 6,500 glass and film negatives with over 400 glass lantern slides and nearly 250 small prints attached to index cards and a similar number of larger prints. The collection is also metadata rich, allowing for the identification of people, places and often dates. Because of the historic connections between the BSA and the Hellenic Society, many of the BSA’s early archaeological excavations are documented in the collection – Phylakopi, Praisos, Palaikastro, Sparta, Mycenae – to name a few. Early study tours of BSA members such as D.G. Hogarth, R.M. Dawkins, F.W. Hasluck, A.J.B. Wace, W.R. Halliday, A.M. Woodward and J. Baker-Penorye are also represented.

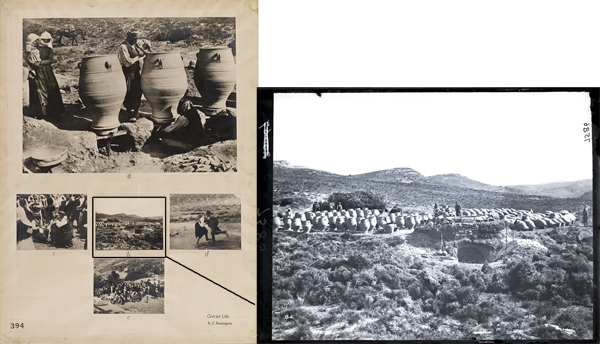

The exchange of photographs in the compilation of institutional photographic collections was common practice in the 19th and early 20th century. It comes as no surprise, given this practice and the close ties between the two organizations, that copies of images from the SPHS photographic collection can be found embedded in other BSA archives. For example, the BSA 1936 Exhibition collection. The 1936 Exhibition at Burlington House in London displayed panels illustrating the activities of the first fifty years of BSA. A number of these panels are contained in the BSA archive and some display images culled from the original SPHS collection, donated to the Hellenic Society by the same BSA students and scholars whose work was represented. An example of a BSA-SPHS image that appears in the 1936 Exhibition is one of a Potter’s camp with kilns in the Pediada district, Crete, b on panel 394. It was photographed between 1901 and 1905 by R.C. Bosanquet (BSA director 1899-1906) who died the year before the exhibition. The panel – in the category of Modern Greek Life – shows images taken by Bosanquet when he was working in Crete of scenes of festivals at Praisos (dancing) and Palaiokastro (wrestling and storytelling), which appear in the BSA-SPHS collection and one that is missing from the collection (SPHS 7594), possibly destroyed at some point in the past, that shows a Cretan potter in the Pediada at work.

Left: 1936 Exhibition panel number 394, Cretan Life. Right: BSA SPHS 01/4993.7586, Pediada Potter’s Camp

Copies of BSA-SPHS images are also found within the approximately 1,000 photographs of the BSA’s archive of the Byzantine Research and Publication Fund (BRF). Robert Weir Schultz and Sidney H. Barnsley, architects trained in the Arts and Crafts tradition, who arrived in Athens on travelling scholarships to study Byzantine monuments between 1888 and 1890 were instrumental in creating the BRF in 1908 which, ever since, has been associated with the BSA. The BRF Archive was compiled between 1888 and 1949 to document the art and architecture of Byzantine & Frankish remains throughout the Byzantine world. An example of an image in both the BSA-SPHS collection and the BRF is the 1908 image by F.W. Hasluck on a study tour in Trebizond (Pontus) of the Byzantine Ayia Sophia church, later in 1584 converted to the Ayasofya mosque.

Ayia Sophia Church in Trebizond (BSA SPHS 01/1083.2901 and BRF/02/02/04/005)

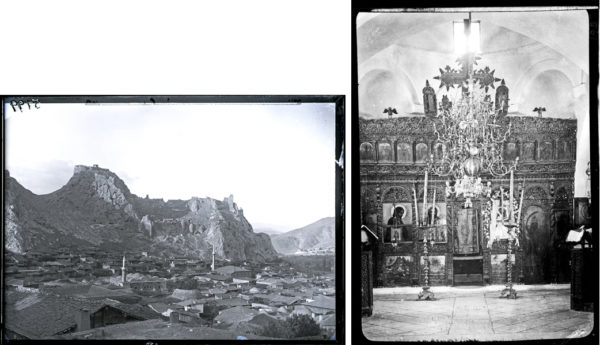

Some BSA-SPHS images appear in both the BRF and the BSA 1936 Exhibition collections. One such image is the view of Tokat (Pontus) with its Byzantine castle on the hill above. This image was donated to the Hellenic Society collection by D.G. Hogarth and J.A.R. Munro, photographed in 1891 when they explored parts of Anatolia. Another is the church screen of Panagia Portaritissa on Astypalaea, photographed by A.J.B. Wace in 1906 when he was touring the Sporades and Dodecanese.

Examples of Images that appear in the BRF, SPHS and 1936 Exhibition collections. Left: Tokat on the Iris river with Byzantine kastro on hill. BSA SPHS 01/2206.5799, BRF/02/02/04/002 and 1936 Exhibition panel 333d. Right: Screen of Panagia Portaritissa (Astypalaea). BSA SPHS 01/1043.2861, BRF/02/01/16/013 and 1936 Exhibition panel 397b

More subtle connections can also be found between the BSA-SPHS collection and collections gifted to the BSA by individuals. The collection I have in mind here consists of photographic prints given to the BSA by Miss Margaret Scott in 1961. In a letter to the BSA, Miss Scott indicates they were from a schoolmasters’ tour of the Aegean around about 1910 or 1912. On the surface, they appear to be totally unrelated to the BSA-SPHS collection. However, I was recently able to document photographs in the BSA-SPHS collection taken by a group calling themselves the Argonaut Photographic Club on schoolmaster’s tours organised by the Hellenic Travellers Club (see: ‘More than Armchair Travellers’ ARGO 8 (2018) 19-21). Most of these Argonaut Camera Club images date no earlier than 1901 and no later than 1904 with a smaller group taken around 1906.

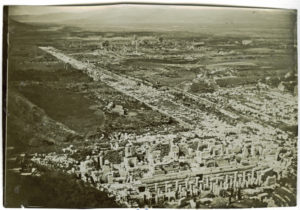

When I started looking at Miss Scott’s photographs, it was clear that names of some of the Argonaut Camera Club donors were marked on the back of the prints. Comparing Miss Scott’s images and those in the BSA-SPHS collection, I noticed that a small number of prints were exact copies. For example, one of Miss Scott’s prints is simply marked with a penciled notation Kensington 7 on the back. This is an exact copy of an image from the BSA-SPHS collection, with 7 Kensington written on the negative border and captioned in the negative register as Corinth: Acropolis, well at foot, donated by T. Kensington. After careful study of the Argonaut Camera Club photographs, I was able to determine that it had been taken by Theodore Kensington between 1901 and 1904.

Left: Kensington 7. Margaret B. Scott Collection: MBS 01/Misc. 11.26. Right: Corinth: Acropolis, well at foot. BSA SPHS 01/2104.5576.

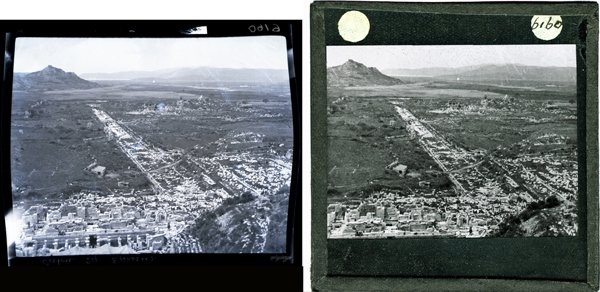

Another set of prints in Miss Scott’s collection are remarkably similar to the BSA-SPHS Hellenic Travellers Club images. Although not exact duplicates, they were most likely taken on the same tours. One example is a print in Miss Scott’s collection, loosely pasted on A3 paper, and simply captioned Ephesus. It is possible, however, to discern the number 28 written on the back of the print.

Ephesus. Margaret B. Scott Collection: MBS 01/Mount 2.61.1

An almost exact image is from the 1906 Hellenic Travellers Club cruise by Dr Richard Caton of a view from the theatre at Ephesus, marked as Caton 29 Ephesus on the border of the negative. It seems likely that these were both originally photographed by Caton. They appear to be sequential frames, Caton having moved his stance slightly between 28 and 29 to capture the scene at a slightly different angle.

View from theatre at Ephesus. Left: Negative, BSA SPHS 01/4905.6160. Right: Slide, BSA SPHS 03/2301.6160.

Coincidently, the Caton 29 image is also duplicated as a lantern slide in the BSA-SPHS collection and is cropped slightly top and bottom from the image in the negative. It can also be found in another collection, the Ashmolean Lantern Slide Teaching Collection, catalogue number XB76 as “Asia Minor: Ephesus, general view”. The collection is now housed at the Institute of Archaeology, Oxford University and is part of the HEIR Project, resource number 39101.

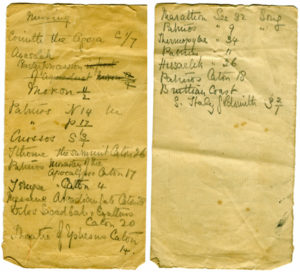

Other photographs show scenes with greater changes in perspective. For example, a print with ‘dug-out’ pencilled on the reverse in Miss Scott’s collection is like the BSA-SPHS image of a dug-out (boat) at Tsagezi near the delta of Penios, photographed by Herbert Awdry between 1903 and 1904. Both show common elements in the background: the same horses, one or two of the same people and a pole leaning against the back wall in the exact same position.

Left: ‘dug out’. Margaret B. Scott Collection: MBS 01/Misc. 12.27. Right: ‘dug-out’ boat at Tsagezi near the delta of Penios. BSA SPHS 01/2113.5585

Since the original BSA-SPHS negatives are dated mainly between 1901 and 1904, but no later than 1906, I began to wonder if Miss Scott mis-remembered the date of her tour since she was uncertain. Her letter clearly states one trip, so the possibility that the collection represents multiple tours of different dates is unlikely. A speculative possibility, on the other hand, would be that photographic prints from previous tours were made available to travellers as mementos, much like postcards. Duplication would be possible during a cruise given the advertised onboard darkroom available for passengers’ use.

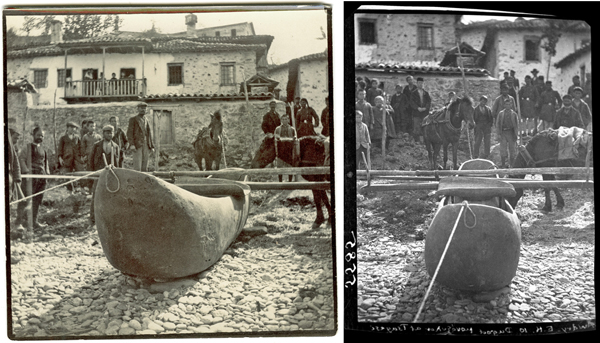

Regardless of the dates of the images, it is clear that some form of photo exchange was going on – or Miss Scott would not have had other photographers’ images in her collection. Another tantalising clue to photo exchange in Miss Scott’s collection is a small note written on both sides, entitled Missing, possibly images that were once in her possession. This note lists places followed by abbreviations that most likely refer to photographers and negative numbers. Moxon, Caton, Lee and Goldsmith are on the list and these people also appear as donors in the BSA-SPHS collection via the Argonaut Camera Club.

Margaret B. Scott Collection: varia

Two of the photographs listed on the Missing note also appear in the BSA-SPHS collection. The photograph called Ithome the summit with Caton 26 exists in the BSA-SPHS collection and is, indeed, an image of the summit of Ithome which also appears as an image in the Byzantine Research Fund. Similarly, Caton 20 is an image in the BSA-SPHS collection of the sacred lake at Delos by Caton.

Caton 26: Ithome. BSA SPHS 01/4885.4281 and BRF/02/01/15/014.

This phenomenon of photo exchange within these BSA photo archives certainly occurred on an institutional level. Both the BSA itself and individuals closely associated with it used the SPHS photographic collection as an archive for images compiled while carrying out their work. This was not the sole raison d’être of the SPHS photographic collection, but it fell within their larger remit. In turn, the BSA as well as other groups used the SPHS collection as a library to pick and choose images for specific purposes. The organisational committee of the 1936 Exhibition selected images to illustrate 50 years of BSA activity. Although the BRF acquired images directly from individuals, it is likely to have used the SPHS to augment its own growing visual collection of Byzantine remains. Yet, other external organisations like the Ashmolean Museum also acquired SPHS images for their own collections. It is also probable that photo exchange happened on a purely personal level– connected indirectly to the original SPHS photographic collection through the mediation of the Hellenic Travellers’ Club.

In Shooting the Past, the photographic curators sought to demonstrate the value of preserving the past by finding connections across disparate collections to tell life stories of ordinary people through time. However, understanding interconnectedness demonstrates there was more going on than simply preserving the past in snap-shots of history embedded in visual data. It sheds light on social practices of the time such as the need to archive visual material and the custom of photographic exchange. It also demonstrates an aspect of how collections once functioned as repositories of visual material. In other words, it adds to the collections’ own life stories.

Deborah Harlan

Honorary Research Fellow

Department of Archaeology

Sheffield University

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.