The Power of Archives: Through the Lens of the Mycenae Excavation Records

View of the Acropolis of Mycenae from the west (taken by author 13/07/2019)

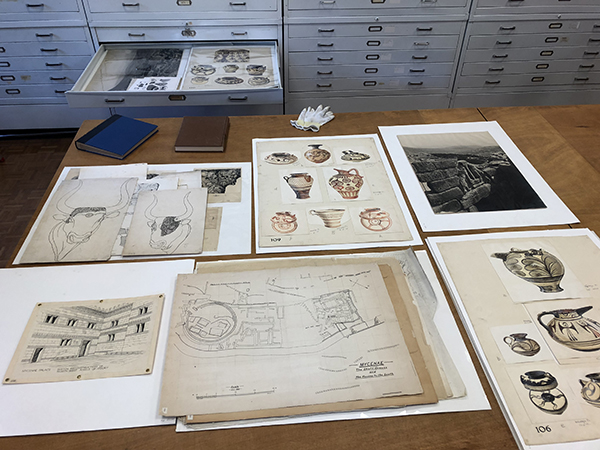

After my first time going through the Mycenae Excavation Records I had seen a mix of beautiful drawings of fragments, some designs of buildings I didn’t know, and a few photos of hills and rubble.

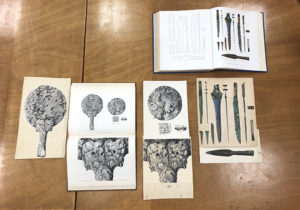

After my second time, I had “organized” the materials. I grouped fragments of pottery and frescos together, put all the drawings of buildings in a pile, and didn’t know what to do with the depictions of jewels, seals, weapons, tools, and figurines.

After my twelfth time, I had all of the drawings numbered, catalogued, and organized. Drawings of pots and sherds were now separate from fresco fragments, and I could identify the types and styles of each. The “drawings of buildings” were now Plans and Sections. Now, I not only knew the differences between them, but had also differentiated final drawings from preliminary ones, and knew the locations and importance of the buildings themselves. Jewels, seals, and plaques were now Small Finds and the workmanship and technique that had gone into creating these artifacts over 3000 years ago was appropriately awe inspiring.

This was the slow, but effective, process by which I came to know the Mycenae Excavation Records, one of the many collections amongst the BSA Excavations Records. It taught me not only the history, culture, and traditions of Mycenae, but more importantly, the immense value and importance of the archive in which these records are held.

Watercolour drawings of jewelry and other small finds from various tombs (from top to bottom: MYC 3/3/10 & 3/3/11; Mycenae Excavation Records)

As you may have guessed, I didn’t know much about Bronze Age archaeology upon arriving at the British School at Athens in May 2019. I had studied Ancient Greek translation in my undergrad so the extent of my Bronze Age knowledge came from translating a few books of the Iliad in my first two years. I had, however, studied my fair share of Archaic and Classical Greek history, and had developed the unfair opinion that previous ages were completely shrouded in myth and conjecture. When, for the second project of my internship, I was tasked with cataloguing the Mycenae Excavation Records of the School, I was excited to expand my knowledge but skeptical as to what level of detail would be available. After immersing myself in the research and cataloguing of the collection, I realized just how mistaken I had been.

I began by simply browsing through the materials to see what we had. They had been partially catalogued long before, although, not according to the current International Standard of Archive Description (ISAD-G). Less than half the records were included on the index cards that made up the old catalogue, and the descriptions that were present could be unhelpfully vague at times. Regardless, it was a start. After a few passes through the records I had identified those from the previous catalogue, those that had been left out, and had organized them all. With the help and advice of the BSA Archivist, I determined an organizational structure and could now begin the process of numbering, researching, and describing every item in the collection. This is where my real development began.

Reconstructed frescos and fragments found throughout Mycenae (clockwise from top left: MYC 3/2/35, 3/2/38, 3/2/36, 3/2/16; Mycenae Excavation Records)

In gathering information on the items I read hundreds of descriptions from various sources, learning the technical names of vases, their styles and designs, what differentiated them from others, and why this was vital to creating an accurate picture of their use and importance to the people who made them. I looked at site maps, topography, plans and sections of buildings, and all of their annotations, slowly bolstering my knowledge of the layout and function, both practical and symbolic, of palaces, houses, tombs, and cemeteries. I saw beautiful frescos bring both important religious events and daily activities of the people to life. I read descriptions of jewelry and the time intensive processes that were mastered to create it. Although I had initially read these descriptions to learn about the items themselves, I had inadvertently gained a functional knowledge of the religion, the culture, and the world of Mycenae.

Dromos and doorway of the Treasury of Atreus with my sister, Shannon, for scale (photo by author 13/07/2019)

Overlooking the House of the Oil Merchant from the Cyclopean Wall (photo by author 13/07/2019)

The extent of the knowledge which I had developed only truly became apparent to me when I was fortunate enough to visit Mycenae after a month of work. Although I stood in jaw-dropped amazement upon first seeing the true size of the Treasury of Atreus, I still knew the names of the various parts, the items found in them, and the histories of the site; both the realistic and Schliemann’s more fantastical. This experience was a reliable microcosm for much of my visit. I was constantly awed by the beauty and preservation of these sites in person, but the underlying knowledge I had developed in the archive remained. To the initial amusement, and likely ultimate annoyance of my younger sister who joined me for the trip, I spent the next few hours excitedly running from location to location, yelling out the names and histories of the various structures before arriving, then ranting through the theories as to why they were built, how they were used, and what the archaeologists found to determine that information.

View approaching the Lion Gate with the Great Ramp visible in the background (photo by author 13/07/2019)

Taking in the views of Grave Circle A, the Cyclopean Wall, and the Argolid valley (photo by Shannon Lawton 13/07/2019)

The reason I mention this development is not to highlight peoples’ ability to learn, nor to suggest that I am now an expert on the Bronze Age, Greek Culture, or even Mycenae – I am most certainly and unequivocally not. Instead, I believe that this development is a powerful argument for the importance of the collection itself and archives in general. By simply exploring the records of the collection I was able to go from knowing very little about a people and their culture, even doubting the existence of that knowledge, to having a solid understanding of their development throughout history.

The beautiful thing about working with the collection is it’s not some seminar where information was tediously fed to students in whatever way the professor deems relevant. On the contrary, the collection allows you to explore whatever you are interested in to whatever depth is necessary. You can go from pottery, to buildings, to grave goods, and back again all within the span of a few days or even hours. It allows you to look at items in new and interesting ways; to explore different theories, to break them down to their logical roots, and evaluate them from new perspectives.

Comparison of published drawings and original water colors from the collection. (left: MYC 3/4/10 and Wace, Mycenae: An Archaeological History and Guide (1949), Imgs. 55 & 56; right: MYC 4/11/1-2 and Wace, Chamber Tombs at Mycenae (1932), Pl. VII

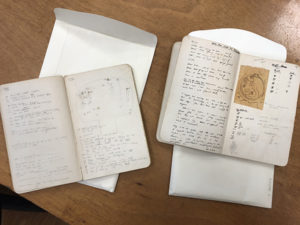

The collection also allows you to look at a history much more recent than that of the culture that was excavated. It gives you the ability to explore the equally important history of the culture performing the excavations. The most obvious sources of this history are field notebooks where the archaeologists themselves list their findings and record their preliminary thoughts and theories. These notebooks allow you to glimpse the items that may not have been glamorous enough for publication, but are still vital to creating an accurate image of the culture. They also take you to the very foundations of the archaeologist’s theories where one can truly evaluate their methodology and accuracy – a necessary step to challenge and further refine our understanding.

Winifred Lamb’s notebooks showing notes and preliminary sketches (left: MYC 1/2; right: MYC 1/1; Mycenae Excavation Records)

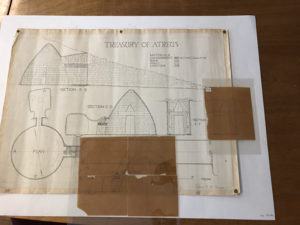

A less obvious source of this history can also be found in the preliminary sketches and drawings created by the artists. While they may not enhance our understanding of the objects themselves, they illuminate the creative process of such prolific artists as Piet de Jong or ones that may have been previously overlooked, like Phyllis Gomme (née Emmerson). For art historians or aspiring archaeological artists, the collection holds an entirely different form of wealth. Being able to watch such a talented artist develop a plan and section from a rough sketch with scribbled measurements, to a semi-final drawing, to a published illustration with annotations is certainly a rare and valuable experience.

Development of Treasury of Atreus sections drawn by Piet de Jong (final: MYC 2/1/30; preliminary: left MYC 2/2/01, right: MYC 2/2/02; Mycenae Excavation Records)

To me, this is what makes archives so deeply fascinating and valuable. Almost anyone from any discipline can find something interesting and critical to their field in a single collection, let alone an entire archive. Archaeologists, Anthropologists, Historians, Historiographers, Artists, Craftsmen, and Political Scientists are just a few professions that come to mind when thinking of who could benefit from the Mycenae Excavation Records alone. Making more archive collections available is therefore necessary if these benefits are ever to be discovered. The only way to truly know how profoundly archives can affect you is to explore for yourself.

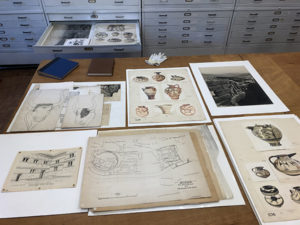

Assortment of Mycenae Excavation Records. (clockwise from top left: MYC 3/4/01, 3/4/02, 3/1/36, 4/09, 3/1/25, 2/1/07, 2/1/29; Mycenae Excavation Records

Although my work necessitated viewing all the materials and their histories, my experience was not inherently more informative than that of any future researcher simply wishing to expand their knowledge. Now that the collection is catalogued, anyone has the capability to review the extensive information, along with the respective citations, and learn as much as they need. The catalogue of the Mycenae Excavation Records will be available for review on the BSA’s Archive Page in the near future.

Tom Lawton

BSA Archive Intern, May-August 2019

Union College, New York, USA

University of Chicago, Illinois, USA

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.