F.W. Hasluck and the Monasteries of Athos: Images from the Archive

In 1911, Frederick W. Hasluck, Student, Librarian and Assistant Director of the British School at Athens, travelled to Mount Athos. Here he systematically photographed the buildings on the peninsula, producing over 130 images of the Orthodox monastic architecture and topography of the Holy Mountain. As was his habit, he donated the negatives to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS). In 2003, the negatives came full circle when a portion of the SPHS image collection came to the BSA archives.

The story of those images of Mount Athos begins with a reference to Hasluck’s activities in the 1910/1911 BSA annual report: ‘[he] made a complete tour of the Monasteries making drawings and architectural studies.’ Shortly after this visit, Hasluck produced an article in the Annual of the British School at Athens entitled ‘The First English Traveller’s Account of Athos’ on early travellers’ accounts of the monasteries. The article used 6 of his own photographs as illustrations. That article was a precursor to a much longer monograph on the subject, a combination travel guide and history. That book, Mount Athos and Its Monasteries, however, only appeared posthumously in 1924. It was illustrated with 27 of his photographs (5 of which had appeared in his previous article) plus a number of his watercolour illustrations based on photographs. In the preface, his wife and literary executor, Margaret Hasluck, indicated that the manuscript had been virtually completed by 1912, but was put aside with her husband intending to revisit Athos after the Balkan War of 1912-13 in order to assess the changes wrought on the mountain. War and ill health prevented him from returning before his death in 1920.

Part One of Mount Athos and its Monasteries is a discussion of the history of the monastic system. The concluding chapter in this part lays out the architectural arrangement of a typical Orthodox monastery. The second half of the book is a guide for the modern traveller – intended as an itinerary – of the 20 monasteries.

Before visiting any of the Monasteries, the village of Karyes would have been Hasluck’s first port of call, as indeed for any visitor to the Holy Mountain, to present their documents. Karyes, named for the abundant hazel trees in the vicinity, is the administrative centre of Mount Athos where the Holy Assembly, comprising representatives of the various monasteries, meets on a regular basis. It is also the primary market town.

BSA SPHS 01/4153.8526: Distant view of the town of Karyes, the main market town and administrative centre

From Karyes, Hasluck began his travels around the peninsula. He would have encountered scenes such as the one below in his approach to the Pantocrator Monastery. Generally, the monasteries are enclosed, forming a four-sided court surrounded by walls.

Many of the monasteries have impressive entranceways, including a number of baldacchino porches, structures made in the form of a domed canopy, often employed in ecclesiastical architecture. Below is the west entrance to the Vatopedi Monastery showing its elaborate baldacchino porch.

Inside the court are ranges of buildings that make up the exterior walls which contain cells, work rooms, storerooms, kitchen and other offices. Hasluck likened this type of architectural plan to a khan (galleried inn), a walled town or fortress, defendable from pirate raids, but restricting the interior space.

BSA SPHS 01/4149.8522: Mount Athos: Range of early 19th century buildings in the S.E. corner of the court of the Xeropotamou Monastery

The refectory, called a trapeza, is sometimes built into a range or sometimes free standing. These structures are often placed next to the kitchen on one side and attached to the main church by the means of an open gallery on another. Hasluck mentions that the trapeza at the Monastery of Great Lavra (seen in the image below) is one of the oldest and finest examples of this type of structure, constructed by the Archbishop of Serres in 1512. Hasluck describes the interior with its “D” shaped marble tables, timber roof, 16th-century paintings, pulpit area in the apse-like space in the longest arm of the cross for reading scripture while dining, and the small rooms in front for the distribution of utensils and plates. He does not include a photograph in Athos and its Monasteries, but, instead, publishes a plan of the structure.

BSA SPHS 01/4574.9413: E. front of the refectory (trapeza) of the Monastery of Great Lavra and fig. 2 on p. 112 of Athos and its Monasteries

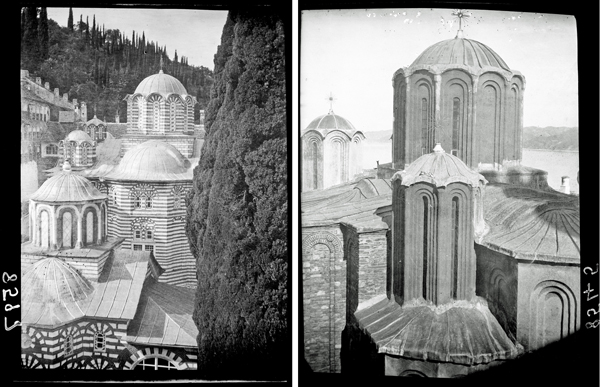

The centre court, however, is reserved for the most elaborate and significant building in the Monastery. The main church (called a katholikon) is located here, often taking up much of the interior space. Below we can see the 18th-century (old) katholikon and the taller 19th-century (new) katholikon in the centre court of the Bulgarian Zographou Monastery. The elongated domes of the 16th-century katholikon of the Moldavian Dochiariou Monastery are seen in the second image below. Architecture varies based on the period of construction and influences based on the origin of the order.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/4224.8597: The old (18th-century) Katholikon and new (19th-century) Katholikon of the Zographou Monastery. Right: BSA SPHS 01/4172.8545: Mount Athos: The apsidal and central elongated domes of the 16th-century Katholikon of the Dochiariou Monastery

Monastery courts often contain a freestanding well and fountain called a phiale. This structure is usually circular with 8 or more columns and a domed roof. The interior of the dome is often painted with scenes. In the centre is the well where water is drawn to bless the various rooms of the monastery on the first of every month and on the festival of the Baptism of Christ.

BSA SPHS 01/4204.8577: The 19th-century clock tower in the S.W. corner and the phiale of the Koutloumousiou Monastery

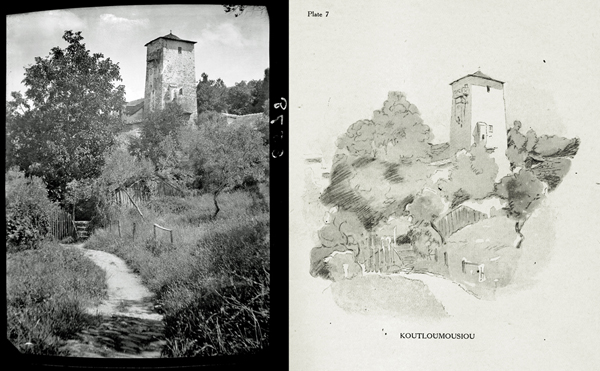

In the image above, in the court of Koutloumousiou Monastery, a clock tower dating to 1808 stands next to the phiale. Another, older tower in the same Monastery can also be seen in the image below from outside the Monastery along with Hasluck’s watercolour illustration in Athos and its Monasteries.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/4205.8578: Mount Athos: The 16th-century great tower of Koutloumousiou Monastery. Right: The Watercolour (Pl. 7) in Mount Athos and its Monasteries is based on the photograph

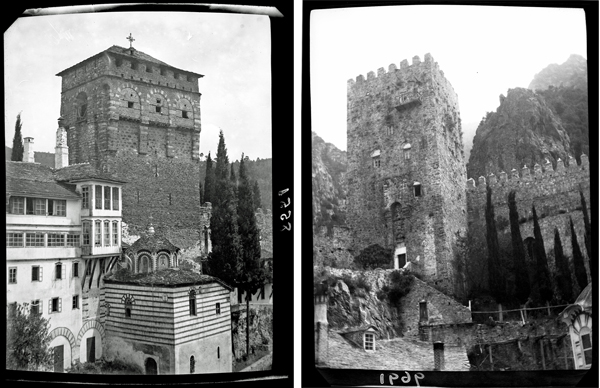

Towers are prominent and characteristic features in the Athos monasteries. They are usually defensive in nature and when built into the walls of the monastery, they overlook strategic points such as entrance gates or are positioned at the highest point. Often, the towers served as libraries or treasuries. The first tower below dates to the 12th century (restored in the 17th century) in the Hilander Monastery, the second to the 16th century in the Agiou Pavlou Monastery.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/4178.8551: The great tower (12th century, restored in the 17th century) of the Hilandar Monastery. Right: BSA SPHS 01/4745.9691: Mount Athos: The 16th-century great tower in the Agiou Pavlou Monastery

Other forms of defensive towers, called arsenals or port towers, are either adjacent to a Monastery, if situated along the coast, or located on the coast closest to its associated inland Monastery. They often include an arch at their lower level which serves as a boat house. Some arsenals are enclosed within their own fortresses. The one below dates to the 17th century, associated with the Ivéron Monastery.

BSA SPHS 01/4208.8581: The 17th-century arsenal tower and boathouse of the Ivéron Monastery from the sea

In addition to the Monasteries, Mount Athos contains other religious settlements. Kelli – meaning cell – describes an isolated house with an “elder” placed in charge where crops were grown and male domesticated animals kept. These are primarily agricultural communities entirely dependent upon their associated Monastery. Sketes, however, define a community made up of a loose collection of monks (ascetics, hermits, recluses). Many sketes are architecturally modelled on Monasteries – a court entered by a gate with a central church. Sketes are generally associated with Monasteries, but do not have a representative vote in the Holy Synod (Assembly). Below is the entrance to the Bulgarian Skete of Bogoroditsa, a dependant of the Russian St. Panteleimon Monastery.

BSA SPHS 01/4195.8568: The Skete of Bogoroditsa, a dependant of the St. Panteleimon Monastery (also known as the Russian or Rossikon Monastery)

Hasluck’s photographs from his 1911 study tour of Mount Athos provide a visual companion to his 1924 monograph, documenting his journey around the peninsula – such as along the cobbled coastal road and across the bridge to or from the Monastery of Great Lavra.

Deborah Harlan

Honorary Research Fellow

Department of Archaeology

Sheffield University

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

For Further Reading:

F.W. Hasluck, 1910/1911. ‘The First English Traveller’s Account of Athos’ Annual of the British School at Athens 17: 103-131.

F.W. Hasluck, 1924. Athos and its Monasteries. London: Kegan Paul.