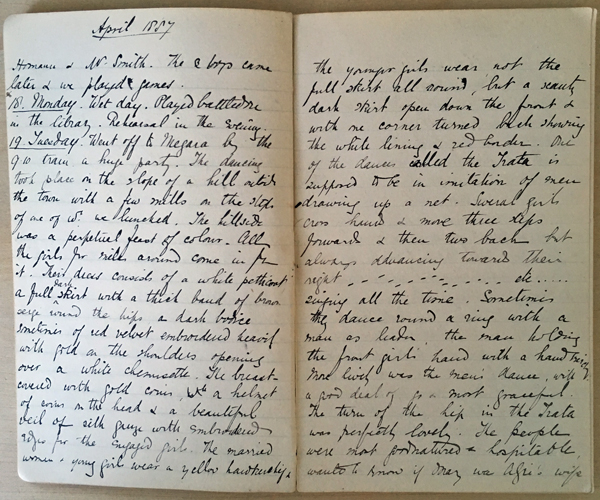

Emily Penrose’s Diary: British School at Athens in 1887

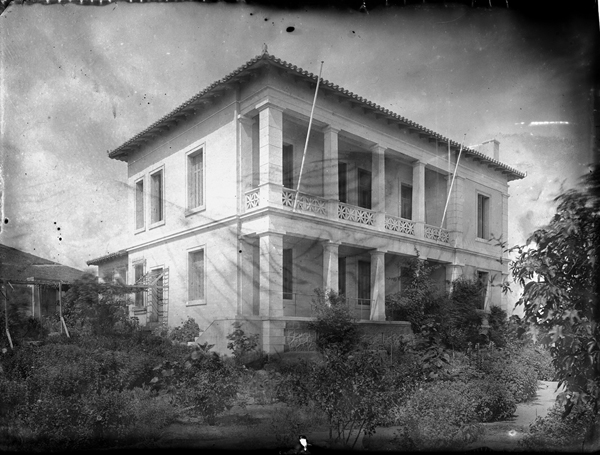

In the various histories of the British School at Athens, there is not much information about the first year of its operation. We do know that the first director was Francis C. Penrose who was also the architect of the first building on the property in Athens (now known as the Upper House). Penrose was resident in Athens from November 1886 to November 1887. Annual reports and official histories mention the first students (E.A. Gardner and D.G. Hogarth) and the various academic and archaeological activities, but none offers an insight into what daily life was like during that first year.

BSA BRF WI.E-40 The Upper House at the BSA ca. 1887-8. One of the earliest photographs of the Upper House from the Byzantine Research Fund Collection, BSA Archives.

Recently, the BSA acquired a diary of Emily Penrose, the eldest daughter of Francis Penrose, which fills that gap. During that first year, Francis Penrose resided in the house he designed along with his wife (Harriette) and three daughters – Emily, Alice and Mary. Emily was 28 years old when she begins to pen her daily entries from March to December 1887, turning 29 on Sunday 18th of September when she enjoyed her birthday by sketching in the King’s Garden (National Gardens). The diary ends with a few intermittent entries in 1888.

Emily’s prose in the diary is often succinct in describing her days such as the entry for Sunday the 31st of July: ‘Dined at Kephissia. Hotel very full’. But, at other times, she digresses into long discourses. People, places, books, music, curious Greek customs and holidays and comments on contemporary archaeological activity and concepts crop up throughout the diary. One of the first events she chronicles in the diary is the ceremony to lay the foundation stone of what would be the first building of the American School of Classical Studies immediately adjacent to the British School. She often remarked that there was a congenial relationship between the foreign schools in Athens (at the time, the French, German, American and British). Along with her family, she was a guest at a soirée at the Schliemanns attended by a ‘good number of English & Americans, German & a Danish contingent’. She went to public lectures, particularly those delivered by her father on the Acropolis, and read Ernst Curtius’ work in the American School library. She engaged with both E.A. Gardner and D.G. Hogarth, the first two BSA students, and regularly went on jaunts to the Acropolis and the Olympieion (which she affectionately refers to as ‘Zeus’ or ‘The Columns’) with American School students.

One of the Greek customs Emily experienced is described in her diary for Saturday the 19th of April when they go to Megara. Here they experienced the Tráta, a traditional commemorative dance performed in Megara on the Tuesday following Orthodox Easter. It should also be noted that Greece was still following the Julian calendar at this time, only adopting the Gregorian calendar (which Emily uses) in 1923. Emily even goes so far as to sketch a diagram of the foot movements of this intricate dance which you can see in the page illustrated below and captured in a photograph about a decade later by John Baker-Penroye.

BSA SPHS 01/1802.4514 Easter dances at Megara by John Baker-Penoyre ca. 1897. From the BSA SPHS Image collection.

Emily was also introduced to many distinguished visitors who came through Athens during the year. For example, Alexander Murray from the British Museum and his wife visited the Penroses, which prompted Emily to read his History of Greek Sculpture. On Monday 23rd of May she accompanied the visiting British artist George Frederick Watts and his wife to the Central Museum (National Archaeological Museum) where Watts explained his ‘theory of curves’ in regard to the composition of sculpture, although from her accounts it is not clear that she was convinced.

Social life in Athens also included eating ices at Solon’s, a fashionable café on Constitution (Syntagma) Square. Calls were made on Sir Horace and Lady Rumbold (British Ambassador to Greece) and other notable British residents in Athens. Tennis parties were organised with members of the American School on the tennis court newly constructed between the two schools. During the hot months, pleasure trips were taken to bathe in the sea at Phaleron where family friends, the Dicksons, resided. Emily was learning Modern Greek from Mr Dickson and her sister Alice would later marry his son, Arthur.

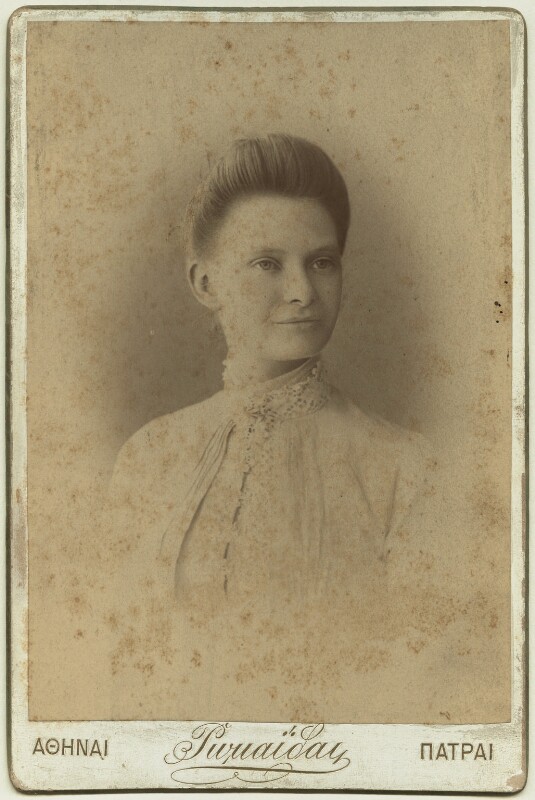

On Monday the 15th of August, Emily remarks that photographs were taken of her and her two sisters by Rhomaides. The Rhomaides (or Romaïdes) brothers Konstantinos and Aristotelis, originally from Bucharest, were photographers established in Patras and Athens. According to the Murray’s Handbook for Travellers in Greece (1884), the studio of the Romaïdes Fréres was located on the rue d’ Hermés (Odos Ermou). They were famous for portrait photography. Remarkably, the National Portrait Gallery in London has this photographic portrait.

In spite of the social whirl, Emily regularly visited various museums, investigated the casts at Martinelli’s workshop on the rue de Patissia (Odos Patission) and made the most of any opportunity to view art and antiquities. One private collection in Athens she visited was that of Constantin Carapanos which she describes in detail.

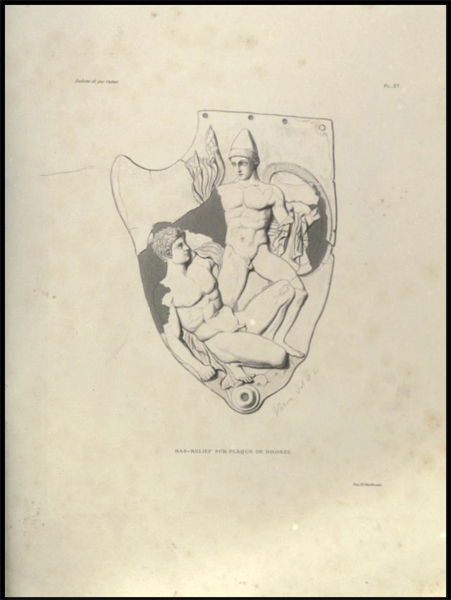

He excavated at Dodona at his own expense & wrote “Dodone et ses ruines.” The collection consists chiefly of ex voto offerings & inscriptions. The most artistic is a cheekpiece of a helmet in repoussé representing the fight of Lynceus & Pollux. There are three plaques of the struggle of Hercules & Apollo for the Delphic tripod. A very curious male siren, an archaistic Jupiter with the thunderbolt, a very ancient & beautiful Athena, a Bacchante & many other human figures & animals. Some of the inscriptions are of the highest interest. One is the dedication by Pyrrhus of some of the Roman arms with some of the arms themselves. Many are quotations asked of the oracle inscribed in thin bronze plaques & rolled up. One is a sort of palimpsest, some large letters AP written over some close small ones. Many of the inscriptions are picked like a child pricks out shapes on paper with a pin.

Carapanos, C. 1873. Dodone et ses ruines vol. II. Pl. XV: “Pollux terrassant Lyncée (géniastère [jugulaire] de casque votif)”

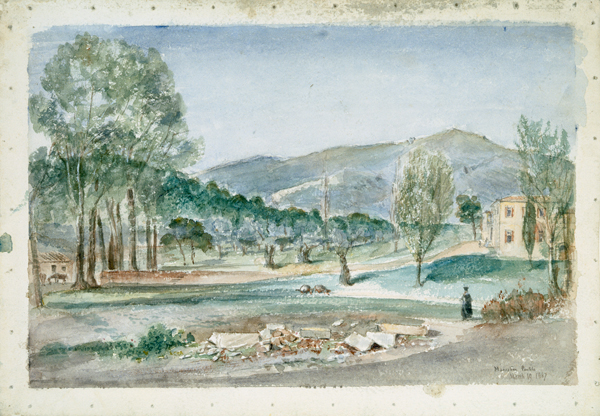

Excursions were also recorded. On Saturday the 19th of March 1887 during a trip to Mt Penteli with her sisters and various friends, she mentions exploring the brigand’s cave – the Cave of Penteli, also known as Davelis Cave after the 19th century brigand who was thought to have used the cave as a hideout. During their ride back down the mountain, they stopped just above the Monastery for a picnic. In the BSA Art Collection are Penrose watercolours, a bequest made by Alice Dickson (nee Penrose) and her niece, Marcia Penrose (daughter of Emily’s brother Frank) in 1938. They were all originally thought to be by Francis Penrose, but given the description in her diary, it is likely that Emily, who was trained as an artist by her father, painted the one captioned Monastery Penteli March 19, 1887. The artwork is impressionistic and includes people and animals unlike the more architecturally detailed watercolours painted by her father.

BSA ART P.01.0019: Watercolour captioned “Monastery Penteli March 19, 1887”. Probably painted by Emily Penrose.

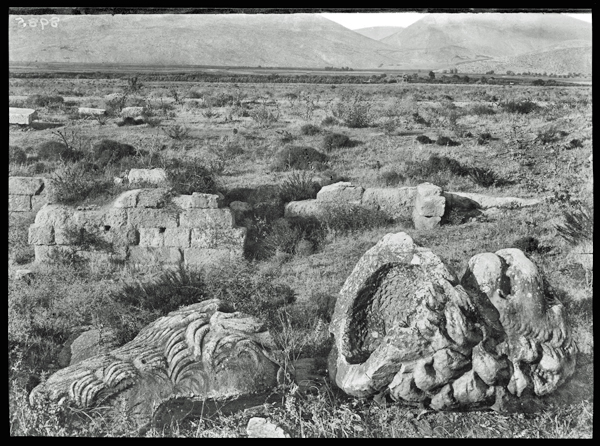

At 7:30am on Wednesday the 27th of April 1887 Emily and companions found themselves on the train to Corinth where they would sail to Itea before spending several days travelling, one of the longest trips she took. The first stop was Delphi where she is surprisingly brief in her description. The route back to Athens overland (riding on mules) was described in more detail. They went through Arachova, past the ancient sites of Daulis and Chaeronea where the ‘lion was all in pieces’. Their way led them to Levadheia and Thebes and past the site of Plataea. Emily ends her narrative by saying: ‘gradually nearer to our old friends Pentelicus & Hymettus & at Eleusis we came to old familiar ground. We were extremely sorry that our lovely holiday was over’.

BSA SPHS 01/4366.8985 An English Photographic Company image of the lion of Chaeronea “all in pieces”, perhaps a similar scene to the one Emily saw. Restoration of the lion happened in 1902, giving a terminus ante quem for the image. From the BSA SPHS Image collection.

The last part of the diary is filled with her descriptions of sights in Italy during the family’s long trip back to Britain from Athens where they were met off the boat by her brother, Frank. Last of all are descriptions of exams and entry into Somerville College (Oxford) where she would become the first woman to gain a first in Greats (Classics). Unfortunately, the diary ends there, but Emily wrote history in other ways: by advancing in her academic career and in 1907 becoming the Principal of Somerville, after holding similar positions at Bedford College and Royal Holloway. She played an instrumental part in gaining women full admission into Oxford University in 1920, allowing them to be awarded degrees for the first time. She was given numerous honorary degrees for academic achievements and, in 1927, she was made a DBE, becoming Dame Emily Penrose. Her 1887 diary is a snapshot of her life at the very beginning of what was to become a distinguished career and provides a glimpse of what life was like at the BSA during its first year.

Deborah Harlan

Honorary Research Fellow

Department of Archaeology

Sheffield University

Emily Penrose Personal Papers collection is now available on the BSA’s Digital Collections, described on the Collection page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Further Reading:

Adams, P. 2004. ‘Penrose, Dame Emily (1858–1942)’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. OUP: Oxford.

Gill, D. 2011. Shifting the Soil of Greece: The Early Years of the British School at Athens (1886-1919), Institute of Classical Studies: London.

John Murray 1894. Handbook for Travellers in Greece Including the Ionian Islands, Continental Greece, the Peloponnesus, the Islands of the Aegean, Crete, Albania, Thessaly, and Macedonia (5th ed.). London.

Macmillan, G.A. 1911. ‘A Short History of the British School at Athens, 1886-1911’ Annual of the British School at Athens 17: ix-xxxviii

Waterhouse, H. 1986. The British School at Athens: The First Hundred Years. British School at Athens Suppl. vol. 19.