Branding Mycenae: Now and Then Images from Social Media to the BSA SPHS Archive

Nearly two million people visit the Peloponnese for tourism every year. In between exploring the beaches, the olive groves, and the stunning mountain hikes, many of us will take in an archaeological site or two: and of the rich cultural menu offered by the Peloponnese, ancient Mycenae, seated majestically on its rocky outcrop, is arguably the most iconic. Naturally, many of these people capture their experiences in photographs.

Undergraduate students and tutors on the BSA Undergraduate Course ‘The Archaeology and Topography of Greece’, August 2019.

Understandably, Mycenae is well featured on Instagram, the sixth most used social media platform and the most popular channel dedicated to sharing photographs. Searching for photographs tagged at ‘Mycenae’ brings up literally thousands of results in seconds, but we can filter through this plethora of photos by looking at what Instagram chooses as its ‘top posts’ — those photographs which have received the greatest number of ‘likes’ from other users. Forty-three photographs tagged as having been taken at Mycenae can be classed as ‘top post’ photos, and these demonstrate not only which parts of the site or subjects the photographers thought were most important, but also the sorts images that were best received by the users of Instagram.

Of these 43 photographs taken at Mycenae, 28 are portraits, 5 are group photos, while 10 depict un-peopled places. The larger number of portrait and group shots is no surprise, as Instagram in its current iteration is generally used as a platform for selfies and filtered images of people. In a few cases, the concept of place is completely irrelevant, as backgrounds behind portrait subjects are blurred to the extent that one cannot identify any features of the landscape. In these cases, the fact that the photos are tagged as located at Mycenae seems rather irrelevant.

In 12 images, though, archaeological material does appear alongside the main portrait focus (see table below). In all cases, a figure occupies the main field of the photo, and archaeological material can be seen in the background. In some senses, archaeology serves as a ‘prop’ to the ‘main’ focus of the photograph. Moreover, accompanying text does not relate to archaeological material, nor in many cases to the portrait subject. The comments attached to such photographs are generally unrelated lines of poetry, artistic statements, or philosophical musings unrelated to the photograph. The combination of art and archaeology is intended to ‘elevate’ the image: the photographers are interested in archaeological material only as general cultural symbol rather than as an entity of specific historic interest.

| Place | No. |

|---|---|

| Lion Gate | 4 |

| Treasury of Atreus | 3 |

| Grave Circle A | 2 |

| Cistern | 1 |

| Palace | 1 |

| Tomb of Clytemnestra | 1 |

But what about place? The five most frequently used geotags used in these ‘top posts’ locate the place generally (‘Mycenae’, ‘Mycenae, Greece’), while the others relate more closely to specific places within the archaeological site (‘Mycenae Lion Gate’, ‘Treasury of Atreus, Mycenae’, ‘Grave Circle A, Mycenae’). However, the frequency with which these tags are used does not necessarily reflect on a close engagement by photographs with these specific places. Five photographs geotagged ‘Mycenae Lion Gate’ are in fact mis-identified and show the cistern, Tomb of Clytemnestra, or Grave Circle A; ‘Grave Circle A’ is tagged for 8 photographs that show general landscape shots or close-up portraits; and one photograph labelled ‘Treasury of Atreus’ illustrates a nearby beach.

On the other hand, a general pattern does emerge. Whether the main focus of an image is an archaeological view, or whether archaeological material only appears in the background of a portrait or group shot, three parts of the site in particular are consistently popular to photograph: namely, the Lion Gate, Treasury of Atreus, and Grave Circle A (notably also places that have their own geotags). Of the 10 non-portrait photographs, five (all correctly geotagged) depict these three locations (three Treasury of Atreus, one each Grave Circle and Lion Gate) as their main focus. The other five non-portrait photographs focus on landscapes, or animals. Furthermore, the captions of these five ‘archaeological’ photos engage closely with the subject matter, offering a date, physical description, or interpretation.

The Treasury of Atreus, Lion Gate, and Grave Circle A all represent Mycenae for our photographers in ways that other parts of the site do not. This is not actually that surprising. These are easily accessible parts of the archaeological site and the state of preservation here is such that there is a lot for the visitor to see. However, is there something more at work here that makes them visual symbols of the site?

To answer this question, we looked through older images of Mycenae from the BSA SPHS collection. Thirty-nine images were chosen as our dataset. These were images presented to the SPHS by individual travellers or acquired by the SPHS from commercial sets, dating from the last decade of the 19th century to the first few decades of the 20th century. Our selection process excluded any photographs that formed part of the excavation archives in the 1920s or were specific archaeological or architectural studies donated by the BSA to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS). The majority of our dataset were converted to slides and made available for lending or purchase through the SPHS photographic library. Like the social media photographs analysed above, they were taken by visitors to the site and made publicly available.

| Category | No. | Slide |

|---|---|---|

| General View | 2 | 1 |

| Monuments (total) | 34 | 21 |

| Lion Gate | 7 | 4 |

| Treasury of Atreus | 7 | 3 |

| Grave Circle A | 7 | 7 |

| Palace Area | 3 | 1 |

| Postern | 3 | 2 |

| Genii Tholos Tomb | 2 | 0 |

| Lion Tomb | 2 | 1 |

| Tomb of Clytemnestra | 2 | 2 |

| Polygonal Wall | 1 | 1 |

| Objects | 3 | 2 |

Most are of specific monuments with a few general views and images of objects (two of niello decorated blades and one of a gold mask). It should be noted that the limited number of objects may be a result of the BSA’s archive selection process from the original SPHS collection which prioritised place (topographical or monument views) – the focus of our study. Of the Mycenae monuments, the three which were most frequent are the Lion Gate, the Treasury of Atreus and Grave Circle A. The Grave Circle remains significant in the list of available slides while the Lion Gate and the Treasury of Atreus still outnumber the other monuments. Unlike the Instagram photographs, these places are generally un-peopled. A focus on monuments was perhaps due to the nature of the SPHS collection as a repository for Hellenic Studies and not as personal photo collections.

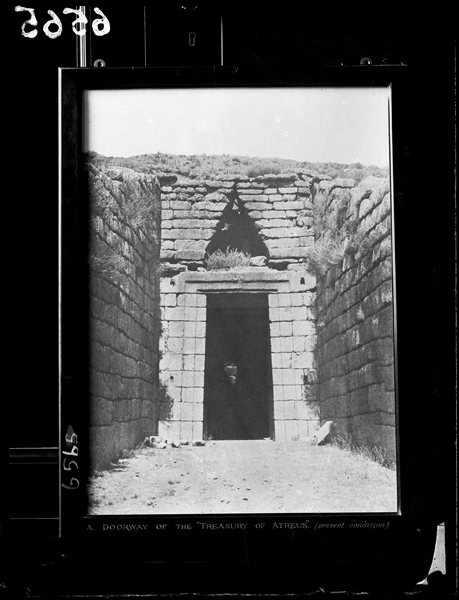

BSA SPHS 01/2416.6565. Captioned “Doorway of the ‘Treasury of Atreus’ (present condition)”, acquired by the SPHS, dated no later than 1906.

BSA SPHS 01/2311.6193. Captioned “Mycenae: tomb” taken by Mr R. O. de Gex ca. 1906, possibly as part of a Hellenic Travellers Club cruise

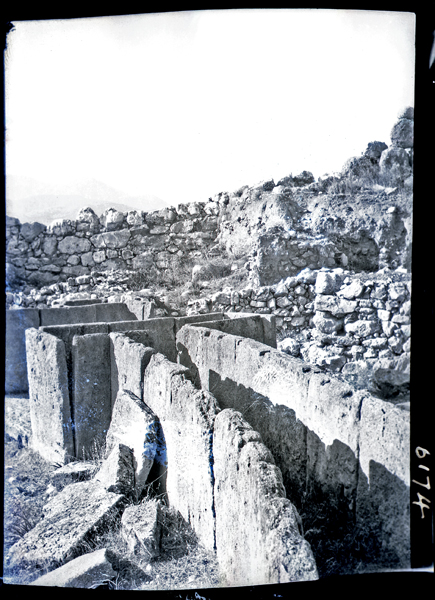

Images from our dataset also appeared in slide sets that were listed at the end of the 1913 SPHS Slide Catalogue. These sets were designed to ‘form a guide’ for lecturers wishing to select images on specific topics. Set VI, ‘Prehellenic Age’, included fourteen images of Mycenae, four of which were monuments and the remainder (10) were objects found at the site, largely the spectacular finds from Schliemann’s excavations of the shaft graves. The four monument slides showed only three monuments: Lion Gate (SPHS 4600), Shaft Graves or Grave Circle A (SPHS 6174) and the Treasury of Atreus (SPHS 2563 and as restored, SPHS 2060). The BSA SPHS Collection has the Lion Gate and Grave Circle image in its collection. Not all of the images from the original SPHS collection survived as many were fragile glass negatives.

BSA SPHS 01/1848.4600. Taken by John Baker-Penroye no later than 1904, Captioned “Mycenae: Lion Gate”

BSA SPHS 01/2306.6174. Taken by Lionel James as part of a Hellenic Travellers Club tour, probably in 1906 and captioned: “Mycenae: shaft grave circle, entrance to”.

The slide sets became even more important after World War I with an intensified drive on the part of the SPHS to promote Hellenic Studies. This was a direct result of a decision in Oxford and Cambridge to remove ‘Compulsory Greek’ from their curriculum, demoting Greek from its previous privileged position. In 1920, the SPHS revived the old slide sets and added new ones, publishing the lists in the 1921 Journal of Hellenic Studies (JHS). In 1923, as a result of demand from the users of the sets, they were transformed from simple lists of slides to either annotated lists or complete illustrated lectures written by experts for delivery in schools and public venues.

The first annotated slide set for the Prehllenic Age was by E.J. Forsdyke and was later updated by F.H. Stubbings in 1939. Forsdyke’s list does not survive, but we have the list assembled by Stubbings. He provides no specific SPHS slide numbers, but from the descriptions, they generally match the slides in the original 1913 list, unaffected by the BSA Mycenae excavations of 1920-23. There were 14 slides listed for Mycenae, five of which show specific monuments: Lion Gate (1), Shaft Graves (2) and Treasury of Atreus (2). All others – apart from one general view of the citadel – are objects mainly from the shaft graves.

The introduction to the List of Sets in the 1923 JHS stated that they were ‘carefully selected’ and designed to bring the ‘most striking and characteristic features of the ancient world before a general audience.’ It is no wonder that the Lion Gate, Grave Circle A and the Treasury of Atreus, as striking or characteristic features of Mycenae, became icons of the site. They continued to be site icons as a quick internet search of vintage postcards and travel posters of Mycenae can attest. Even current postcards and the Greek postcard stamps of Mycenae (issued in 2019) tend to highlight these three monuments. For our present-day Instagram photographers, reinforcement of these symbols through time may have played an unconscious part in the choice of place, regardless of their archaeological significance, as the monuments had long been and continue to be essential to the ‘brand’ of Mycenae in the public imagination.

Michael Loy

Assistant Director

British School at Athens

Deborah Harlan

Honorary Research Fellow

Department of Archaeology

Sheffield University

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.