Petrie @ BSA

Mr. Petrie, too, came from Egypt to join us for a time, and his valuable work on the Mycenae discoveries will soon appear in the Hellenic Journal.

The quote above appears in the British School at Athens (BSA) Annual Report by the Director, E.A. Gardner, for the academic session 1890-1891. In this Annual Report, Gardner wrote extensively on the year’s excavation season at Megalopolis, the academic activities of the current crop of students, and the list of BSA public lectures given in Athens. He concluded his report with a list of visitors to the BSA, tacking on the sentence quoted above at the very end. It is easily overlooked among the reporting of the BSA’s activities.

But, if we take a closer look at Petrie’ visit, it will prove to be rather more significant than at first glance among the BSA activities of 1890-1891. The article alluded to by Gardner appeared in The Journal of Hellenic Studies (JHS) in 1891, later in the same year that Petrie visited the BSA. It was entitled ‘Notes on the Antiquities of Mykenae’. In this article, he examined objects from 6 graves of Grave Circle A excavated by Schliemann.

Petrie’s work on linking objects found at Mycenae and in Egypt developed ideas he had formed earlier after finding Aegean pottery in his 1889-90 excavations at the Egyptian sites of Kahun and Gurob. He realised then that the absolute chronology of Egypt, based on its historical records, would help build a relative chronology for the Aegean. He first presented his thoughts on the subject in an article published in the 1890 JHS (‘The Egyptian Bases of Greek History’). Although, according to Jacke Phillips in her 2006 article on Petrie and Aegean chronology, scholars – many of whom were classicists – viewed Petrie’s deductions with suspicion. This spurred Petrie to visit Greece to study Mycenae excavation material first-hand. Entries in his diary provide a fuller picture of this visit than E.A. Gardner’s one sentence in the BSA’s Annual Report. He begins with the following:

April 24th. Piraeus by 9. Drove up. Called on Gardners. Lunched there. With Gardner over Mykenaean collection +c in aft. Moved to Grand Hotel. (Petrie, Journal III: 23, quoted in Phillips 2006: 145)

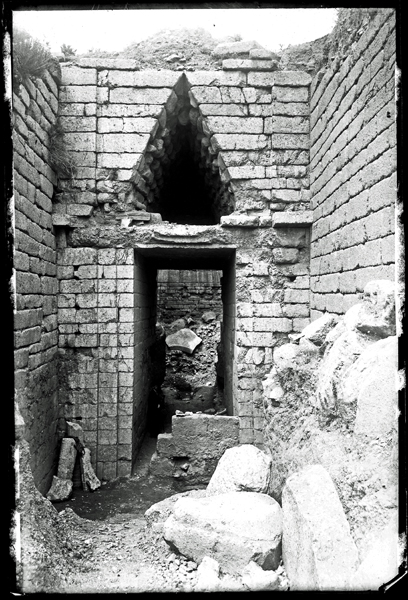

The ‘Mykenaean’ collection he mentions came from both Schliemann’s and Tsountas’ more recent excavations. Petrie indicated that the material was housed in the Polytekhnion, which probably refers to the Collection of Fictile Vases in the Museum of the Archaeological Society housed at that time in the Polytechnic next to the Central Museum (now the National Archaeological Museum). The ‘+c’, shorthand for etc., no doubt referred to other material he was shown in the afternoon (‘aft’), including a ‘fine Egyptian collection’. The Grand refers to a hotel popular with foreign travellers which was located on Syntagma Square, mentioned in both Baedeker Guides and Murray’s Handbooks for Travellers to Greece. Further entries in his Journal give more details of this 19-day stay in Greece. During that time, he toured the Argolid including the sites of Mycenae and Tiryns with his friend, Walter Leaf, who happened to be Treasurer of the BSA. Leaf must have taken his photograph of ‘Mrs Schliemann’s Treasury’ (later named the Tomb of Clytemnestra) during this tour.

BSA SPHS 01/0368.1680: Mycenae, “Mrs. Schliemann’s Treasury” showing the latest excavations (W.L. Enlargement No.13)

Returning to Athens after his short tour with Leaf, Petrie moved in with the Gardners at the BSA. At the time the only building on the premises was the one now known as the Upper House. The house did duty as the Director’s residence, the BSA library and a hostel for a limited number of students or visitors. Here Petrie used the library to write his 1891 JHS article based on his observations which substantiated his earlier chronological claims, but now on the basis of material from Mycenae itself, not from Egypt. According to Petrie’s Journal, Gardner had read the article before sending it off to the JHS and referred to it as Petrie’s ‘heresy’ and indicated that Petrie had done more in a week to clear up the matter of Mycenaean chronology, from an Egyptian basis, than others had done in years.

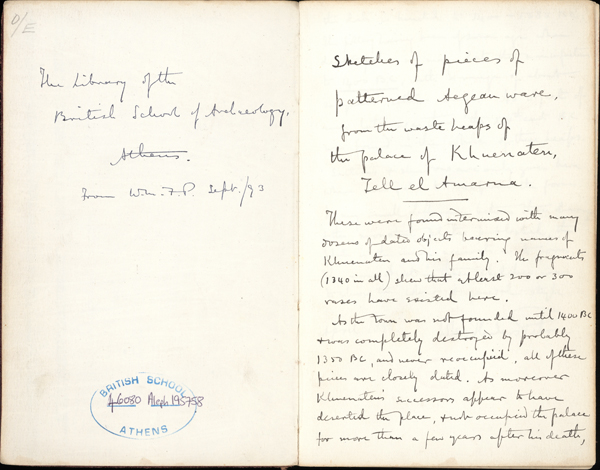

A year after his visit to the BSA and his examination of Mycenaean material in Athens, Petrie returned to Egypt to excavate Tell el Amarna, the capital city of Akhenaten, or (as Petrie refers to him) Khuenaten. During the 1892 excavation season, Petrie found more Aegean pottery. A sample of this Aegean pottery was drawn as watercolours that Petrie pasted into a notebook. That notebook with a handwritten preface dated to April 1892, was presented by Petrie to the BSA as a gift in September 1893. In the following year, his publication Tell el Amarna appeared.

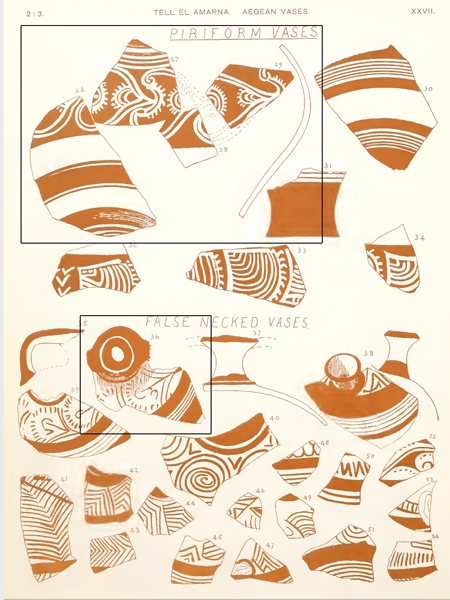

A quote from Petrie’s Tell el Amarna makes clear the significance he attached to the connection between Greece and Egypt: ‘The Aegean pottery is however more important, as there is no indication that it was ever made in Egypt; and its presence therefore shews the coeval civilization of the Aegean countries with which it is always associated’. In the publication he categorises Aegean pottery primarily in terms of shapes, but also decoration: pyxides, bowls, piriform shapes, false-necked vases, conchoidal patterns, and thick matt-faced pottery. He adds on Cypriote and ‘Phoenician’ shapes to the list of ‘Aegean’ imports.

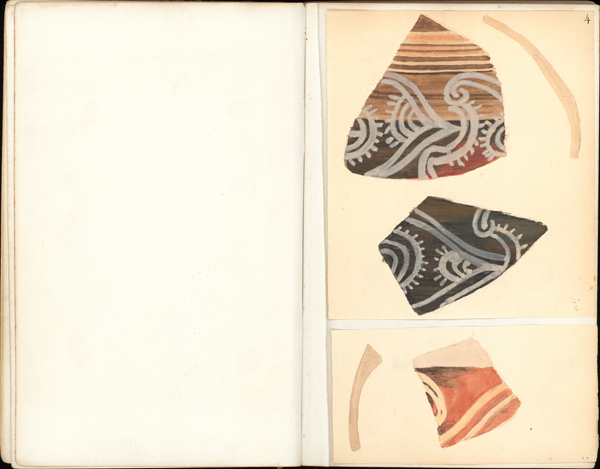

The table of contents in the BSA Petrie notebook match these categories, indicating that the watercolours of sherds are a representative sample of the Aegean pottery he found at Tell el Amarna. The majority of the watercolours in the notebook match monochrome illustrations shown in the five plates of Aegean pottery in Petrie’s Tell el Amarna publication. In his written preface to the notebook, Petrie (who must already have been planning publication) remarks that the monochrome plates in the publication are a more accurate representation of shape, but the watercolours in the notebook provide more sense of colour and style.

Plate from Petrie’s 1894 publication, Tell el Amarna, highlighting some examples of sherds drawn in the BSA Petrie notebook

WMFP 1/1 p. 4. Watercolour of sherds from a ‘piriform vase’. Corresponds to Petrie 1894: pl. XXVII.27 to 29

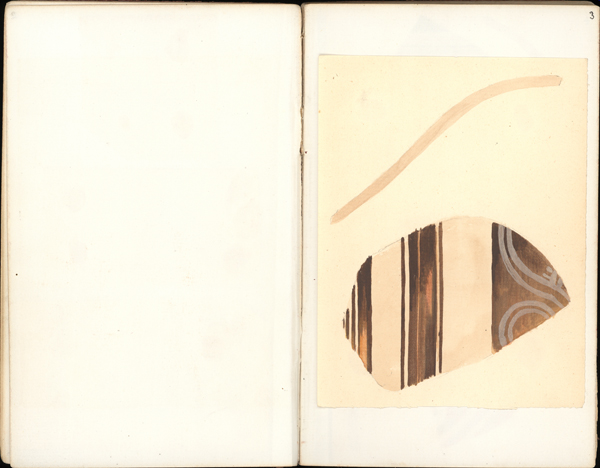

WMFP 1/1 p. 3. Watercolour of sherds from a ‘piriform vase’. Corresponds to Petrie 1894: pl. XXVII.26

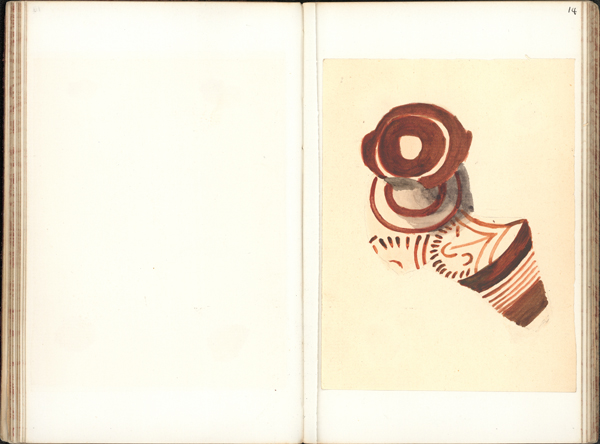

WMFP 1/1 p. 14. Watercolour of a sherd from ‘false necked vases’. Corresponds to Petrie 1894: pl. XXVII.36

William M. Flinders Petrie is best known as a pioneering Egyptian archaeologist who transformed the practice of archaeology in Egypt with his precise excavation techniques, particularly his close attention to pottery seriation and its significance as a chronological indicator. It is clear that he also played a part in the development of Aegean prehistory, particularly in building its chronology, although not without initial resistance among classical scholars and much later fine-tuning of the absolute chronological sequence.

The notebook is now available on the BSA’s website via the Digital Collections.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Deborah Harlan

Honorary Research Fellow

Department of Archaeology

Sheffield University

Further Reading:

Petrie, F.M. 1890. ‘The Egyptian Bases of Greek History’ JHS 11: 271-277.

Petrie, F.M. 1891. Illahun, Kahun and Gurob: 1889-1890. London: David Nutt.

Petrie, F.M. 1891. ‘Notes on the Antiquities of Mykenae’, JHS 12: 199-205.

Petrie, F.M. 1894. Tell el Amarna. London: Methuen

Phillips, J. 2006. ‘Petrie, the “Outsider Looking On”’, pp. 143-157 in Darcque, P., Fotiadis, M. and Polychronopoulou, O. eds, Mythos: la préhistoire égéenne du XIXe au XXIe siècle après J.-C.: actes de la table ronde internationale d’Athènes (21-23 novembre 2002). Paris: École Française d’Athènes.