Through the Female Lens: Women Travellers’ Photography and the BSA SPHS Collection

One of the benefits to cataloguing the large BSA-SPHS photographic collection is teasing out stories. The images tell the stories, but they were created by individuals who photographed and/or donated the images to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS). People have motivation. First, they determine what to photograph, then they choose which photographs to donate to the SPHS. Once they are in the SPHS collection, another selection process goes on within the Society to decide how to organise and decide which are to be duplicated as slides for use in teaching. By the 1920s (about 3 decades after the collection was formed) sets of images were also selected for pre-defined topics: some with accompanying pre-written lectures or annotated lists. These decisions affect the image’s visibility and, as a consequence during the life of the collection it attributes value to the image – or the reverse, it regulates the image to obscurity. The collection slowly ceased to function as a lending library shortly after WWII when new technologies in the form of 35mm slides began to take over. In 1967 the old photographic collection officially became inactive and was placed in storage. In the first decade of the 21st century, the collection was slated for disposal. It was at this time that the British School at Athens (BSA) acquired a portion of the collection. The BSA selected images based on donors’ association with the BSA or images of topographic interest, particularly in areas where the BSA had worked. All of these choices, from the initial click of the camera onward – contributed to the formation of the present collection.

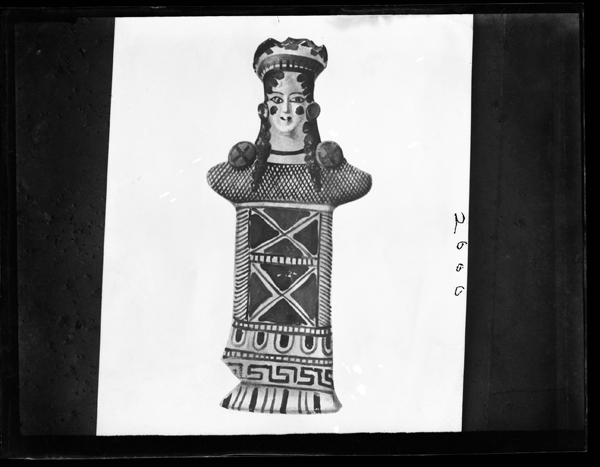

Taking into consideration how the BSA-SPHS dataset was formed, this Archive Story explores photography by women. While the majority of donors to this collection are men, women are represented. Many of the male donors had scholarly associations with the BSA and at least three women donors also had strong ties to the BSA: Jane Harrison, Eugene Strong (née Eugene Sellers), and Hilda Lorimer. Jane Harrison’s images, some of the earliest donated to the collection, were primarily copies of commercial images (see related Archive Stories: Rule II and The English Photographic Company). Two images, one a copy of a photograph taken by Wilhelm Dörpfeld, come from Eugene Strong, the first female BSA student who later became Assistant Director of our sister institution, the British School at Rome. Hilda Lorimer’s contribution in the BSA-SPHS collection was limited to one image – a copy negative of a photograph showing a drawing of a figurine from the archaeological site of Rhitsona. Since nearly all of the limited number of images donated by Harrison, Strong and Lorimer were copied as slides and made available to SPHS members, it is likely that what these three women chose to deposit (or were asked to contribute) was based on contemporary academic ideology – that is, what would be expected in a collection of teaching images reflecting Hellenic culture.

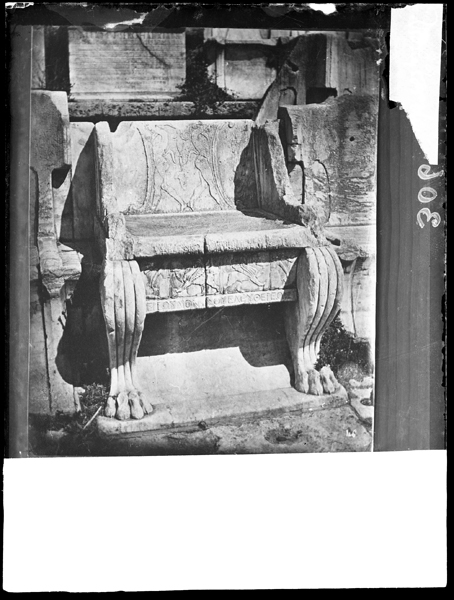

BSA SPHS 01/0039.0306. Athens Acropolis: Chair in the Theatre of Dionysus (English Photographic Company image donated by Jane Harrison no later than 1897).

BSA SPHS 01/0192.1305. Eretria: Theatre excavations (donated by Eugenie Strong, photographed by Wilhelm Dörpfeld ca. 1891)

BSA SPHS 01/0541.2000. Rhitsona (Mycalessus): Drawing of Female terracotta figurine (donated by Hilda Lorimer ca. 1907)

The remaining women in our collection tended to be members of the SPHS. John Penoyre, long-term secretary of the SPHS (1902-1936), was known to have expanded the membership and encouraged teachers and younger members to join. It is perhaps in this context that more women engaged with the Society in the early part of the 20th century. Most were unmarried, carrying the title of Miss, and many were likely school teachers/head mistresses listed with addresses at schools, and it is likely that some had independent means. Some of the women donors were also members of the Hellenic Travellers’ Club which had started primarily as a vehicle to provide teachers with a first-hand experience of the Hellenic world (see Archive Story: Argonauts Abroad). It is not surprising that most of the images from women donors in the SPHS photographic collection appeared to come from touring. John Urry in his book, The Tourist Gaze, characterises women travelling to Greece in the late 19th and early 20th century as educated and having the independence to allow travel. This profile appears to fit female members of the SPHS and donors to the photographic collection.

I used the following criteria to select images by women in this study: only photographs from women who gave more than a handful of images – preferably in the form of original negatives, that were catalogued together in the negative register, and taken at more than one place. Original negatives increases the likelihood that the donors were also the photographers. There is a chance that they were taken during the course of a single tour if donated at one time. The larger number of negatives also maximizes the possibility of wider geographical coverage and provides more variability in subject matter. Subsequently the women who donated images to the SPHS from the earliest cruises of Hellenic Travellers’ Club from 1901 to 1906 were ruled out as their contributions tended to number one or two images each. However, four women did meet the criteria: Miss Gorse, Miss Skeat, Miss Janet Lowe, and Miss Rutherford.

| Name of Donor | Number of Negatives | Duplicated as Slides | Negative Type | Number of Places |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miss Gorse | 9 | 6 | original film | 3 |

| Miss Skeat | 12 | 0 | 7 original film; 5 glass copy negatives | 3 |

| Miss Janet Lowe | 40 | 19 | 39 original film; 1 duplicate film | 13 |

| Miss Rutherford | 25 | 25 | original film | 12 |

These women are not well-known, making it a challenge to research their backgrounds and their interactions with the SPHS, all pieces of information that are helpful in understanding motivation in capturing of the image and selection for donation. In order to research links to the SPHS, I went first to the membership lists which were published in the Front Matter of the SPHS publication, The Journal of Hellenic Studies (JHS), comprehensively until 1931 when the format changed and only those elected that year were listed. Similarly, donations to the photographic collection are listed until 1933 in the Proceedings of the Society, also published annually in the JHS. All but Miss Gorse were members of the SPHS and/or listed as donors to the photographic library. Miss Margaret F. Skeat was a school mistress and scholar of French literature who became an SPHS member in 1926. Not much is known about Miss Janet Lowe, but she is said to have donated her images to the SPHS in 1927. Miss Helen Rutherford is listed as a member in 1930 with a Scottish address, but she donated images some years earlier in 1927.

We also do not know how many more images were taken during these touring events, but we can extrapolate motivation for donation based on the subject matter of the photographs that ended up in the SPHS collection. Two of the women have quite small collections – from 9 to 11 – making assumptions speculative. Miss Gorse’s collection of nine photographs are mostly of Delos, but one each from Delphi and the island of Ithaca. Her negatives are annotated on their borders with her last name plus a number. This form of marginal annotation and the the locations depicted are similar to many produced by the Hellenic Travellers’ Club, suggesting she may have been part of a later Club cruise. Miss Skeat’s collection of 12 images can be broken down to the 7 original film negatives that show scenes of archaeological monuments in the Argolid and Athens. The remaining 5 negatives are glass copy negatives which may originate from commercial images.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/4470.9182, Cave of Cynthus at Delos (Miss Gorse). Right: BSA SPHS 01/6238.C4127. Tiryns: entrance to covered passageway (Miss Skeat)

The two other women, Miss Lowe and Miss Rutherford have larger collections, both of which consist of original film negatives. Miss Lowe’s images are in two groups, each in a different negative format, that may reflect two separate tours – and possibly using different cameras. The first set of negatives are a slightly larger size and depict Delphi, Athens, Eleusis, Marathon, Phyle, Asine, Epidaurus and Tiryns. The second group of smaller negatives are catalogued later in the negative register and depict Mt. Olympus, Pharsala (Thessaly), Monemvasía and Knossos. Miss Rutherford’s collection shows the Ionian islands of Corfu and Ithaca, areas near ancient Stratos and Missolonghi in Western Greece, Meteora in Thessaly, ancient Delphi, Thebes and Athens.

The dates of these women’s images vary, but most can be dated in the first few decades of the 20th century. Terminus dates in which the images were produced are based on dates of donation to the SPHS or dates they were duplicated in slide format and added to published accessions lists. Dates can also generally be confirmed and refined by details in slide captions and clues in the images. The earliest listed in the negative register are those from Miss Gorse who probably toured Greece in the first decade of the 20th century, likely prior to the outbreak of WWI in 1914. Miss Rutherford, Miss Skeat and Miss Lowe fall into the interwar years. Although Miss Rutherford’s donation to the collection is reported in the 1927 JHS Proceedings, most of her images are accessioned in the 1925 slide catalogue. In addition, a tantalising parenthetical note in the caption of the catalogue for Miss Rutherford’s image of dancing, fustanella garbed soldiers of the Royal Guard states (temp. King George), is most likely a reference to King George II of Greece who became king in 1922 after the assassination of his father (King Constantine I) and abdicated with the declaration of the Second Republic in 1924. Therefore, it is possible that Miss Rutherford took her photographs on a tour conducted between 1922 and 1924. We also know Miss Skeat’s and the first group of Miss Lowe’s earlier group of negatives were catalogued in the 1927 accession of lantern slides, giving us a terminus date for these. A small figure of a women wearing 1920s style clothing in one of Miss Skeat’s photographs confirms a general date of the 1920s. The second group of Miss Lowe’s negatives in a smaller format date no earlier than 1931 since an image in this group shows the House of the High Priest at Knossos that was excavated at that time, one of the last buildings Evans investigated.

BSA SPHS 01/7762.C3245. Athens: Soldiers of the Royal Guard (temp. King George) dancing (Miss Helen Rutherford)

In his classic book, Ways of Seeing, John Berger tells us that our impressions of images are culturally learned, so an image will speak (i.e. send a visual message) differently to different individuals. There is also a matter of historic perceptions, often divergent from our own, when dealing with older photographic archives. In other words, the process of interpreting what Miss Lowe, Miss Gorse, Miss Rutherford and Miss Skeat saw when they composed and photographed views is complex, dependant on understanding cultural and social ideas of the past. However, the subject matter of these women’s photographs may provide a clue to the visual message the photographers intended.

Martha Klironomos in Women Writing Greece analysed British women’s travel writing the late 19th and early 20th century and has categorised these women authors into two polar opposite categories: archaeological-topographical and sociological-anthropological. The first group focuses on the legacy of Greece’s past, diminishing the present. The second includes discussions of contemporary Greek life that range from descriptions of romanticised folk displaying residual characteristics of the glories of their ancient past to a degraded “other” as orientalised subjects. Although photographs are more intangibly encoded than the written word, it is possible to look at our photographs and determine if this analysis holds up.

Both Miss Gorse and Miss Janet Lowe appear to fall into the first category of archaeological-topographical observations. For the most part, they restrict themselves to antiquities, often in empty landscapes. For example, Miss Gorse shows no individuals in her view towards Rheneia through the columns of a Roman house at Delos. Although most of Miss Lowe’s images are stark images of antiquities, some of her images show people, but safely from a distance at well-populated sites such as the Athenian Acropolis in her image of the Erectheum.

Miss Skeat and Miss Rutherford, on the other hand, might fall into the sociological-anthropological category. It is clear that both Miss Skeat and Miss Ruterford intentionally photographed or collected specific ethnographic subjects with no antiquities in view. Yet, they also photographed ancient monuments devoid of or mitigating modern life such as in the images above showing Miss Skeat’s photograph of Tiryns with visitors disappearing down the passage and Miss Rutherford’s view of the temple at Stratos. The 5 glass negatives donated by Miss Skeat were most likely acquired by her from commercial sources and consist of scenes of domestic activity and pottery production: ancient and modern storage jars side-by-side, a drawing of an outdoor baking oven, a travelling Cretan potter at work, a modern pot market at Chalkis in Euboea and a modern pottery workshop. Miss Rutherford appears to have been interested in people she encountered – some engaged in activities, and others simply posed. Both sought to capture the present they encountered, the “otherness” of the people particularly identified by native costume, and reflected activities with past practice.

BSA SPHS 01/7749.C3232. Ploughing scene around Lake Amvrakia near the village of Rivio. (Miss Helen Rutherford)

So, it does not seem that women photographers can be divided clearly into the categories of archaeological-topographical and sociological-anthropological. Nor can it be said that women, as a gender, tended to photograph contemporary people and activities. They were also interested in the ancient monuments in their pristine – non-modern – setting. And, as we have seen in a previous Archive Story: Relics of the Past, women were not the only ones contributing to sociological-anthropological observations. Many male scholars during study trips or tours would also capture scenes of modern life.

According to Elizabeth Edwards, another way of understanding how these images were viewed is by looking at how the photographs were grouped and categorised to create historical ‘ways of seeing’. In other words, the collection management strategies within the institution of the SPHS were significant in assigning secondary meaning to the images. The fact that the majority of the images from these women (with the exception of Miss Skeat) were duplicated into slide format for the lending library attests to the value placed on them and their appeal to SPHS members for use in teaching. The images selected for slides were categorised under the following headings in the SPHS slide catalogues: Topography & Excavation organised by geographic location, Sculpture, Architecture and Miscellanea – the latter containing the sub-category Modern Greek Life. The images that were not selected to be converted into slide format tended to be duplicate views of well-known monuments that were already available in the collection .

All of Miss Rutherford’s 25 images appear in the 1925 slide catalogue. All but two were placed in the Topography & Excavation category. The two left out were placed in Miscellanea, Modern Greek Life: the group of shepherds at Stratos and the Royal Guards in foustanella in Athens (shown above). I find it interesting that her other images of modern Greek life are placed in Topography & Excavation. Some do not contain ancient monuments or their settings, the usual reason for placing images in this category. They do, however, show modern life in modern topography: such as the Saraktsani straw huts near Missolonghi, the ploughing scene on the fertile ground around Lake Amvrakia (close to the village of Rivio) shown above, and the Pélekas women from Corfu in traditional costume.

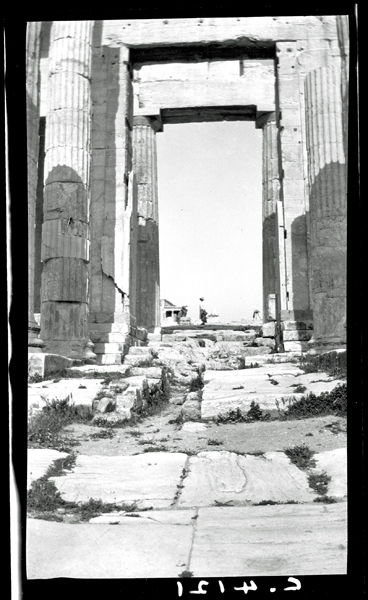

An image of the Propylaea in Miss Lowe’s collection was also used in two pre-written lectures with set slides: Ancient Athens written by Stanley Casson in 1924, and The Acropolis of Athens written by Arthur Hamilton Smith in 1933. Both authors used Miss Lowe’s image to illustrate the use of Ionic and Doric architecture combined in one monument. Like the pre-written lectures with slides, annotated slide lists were also created around a specific subject such as Modern Greek Country Life compiled around 1932 which contain a number of images from Miss Rutherford’s collection – including those originally classified as Topography & Excavation in the SPHS slide accession list.

Travel photography by women, like its textual counterpart, offers the potential to observe how women interpreted and interacted with Hellenism through the lens of their cameras. The subsequent categorising and grouping of images by the SPHS (often forcing them into specific categories) also provide us with insights into how the Hellenic world was viewed in late 19th and early 20th century. This process of interpretation is on-going and even now these images will acquire another layer of meaning when our modern eye looks at and interprets these historic images.

Deborah Harlan

British School at Athens

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Further Reading:

Berger, J. 1972. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books.

Edwards, E. 2016 ‘Institutions and the Production of “Photographs”’ Fotomuseum blog, https://www.fotomuseum.ch/en/explore/still-searching/series/29333_institutions_and_the_production_of_photographs

Edwards, E. 2017. ‘Location, location: a polemic on photographs and institutional practices’ The Science Museum Group Journal 7, http://dx.doi.org/10.15180/170709

Harlan, D. 2018 ‘More Than Armchair Travellers’ ARGO: A Hellenic Review 8: 19-21.

Klironomos, M. 2008, ‘British Women Travellers to Greece, 1880-1930’, pp. 135-157 in Women Writing Greece: Essays on Hellenism, Orientalism and Travel edited by Vassiliki Kolocotroni and Efterpi Mitsi, Rodopi: Amsterdam.

Urry, J. 1990. The Tourist Gaze: Leisure and Travel in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage Publications.