Exploring Conscious and Unconscious Decisions in the BSA Map Collection

Library Science recognises that knowledge organisation systems, grouping related materials together, impose particular views of the world. Conscious and unconscious decisions play a part in how these organisational systems are created. In Part I of this Library Story, I explore how the BSA Map Collection was organised and the implications of that for its use. Part II focuses on how the maps themselves demonstrate another act of conscious and unconscious decision-making. Mark Monmonier’s classic 1991 study, How to Lie with Maps reveals that mapmakers consciously or unconsciously made decisions on what to depict in geographical space, telling one of many possible stories. Keeping this caveat in mind, I explore how some of the historical maps tell stories of modern Greek history.

Part I: The Knowledge Organisation System

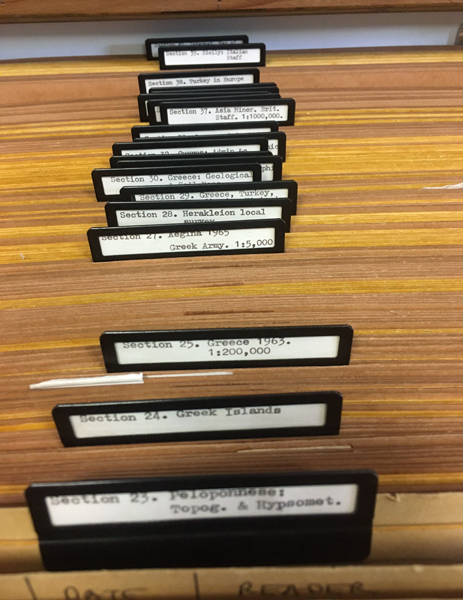

In 1952 the Assistant Director, John Boardman, rearranged the BSA map collection. We do not know how the collection, accumulated since the institution was founded in 1886, was organised prior to this time. In addition, many of the older maps – the Rare Map Collection – were not integrated with the others and not included in the organisational scheme. For the most part, the physical organisation of the maps still follows the categories or “Sections” Boardman devised, even after some minor re-organisation in the 1990s when vertical map cabinets had been installed. More maps were acquired since Boardman’s time which appear to have been slotted into his original scheme or were tacked onto the end, as in the case of the large set of 1969-1977 Hellenic Army maps. Although this organisation was a conscious decision on Boardman’s part, it indicates an unconscious point of view. Much can be learned about how the BSA Map collection was viewed and used in the second half of the 20th century simply by looking at how it had been arranged.

British staff maps from WWII, which had been presented to the BSA shortly after the war ended (sections 1-8), mid-19th century British Admiralty charts (sections 9-12), and the 1901-1919 British Intelligence maps of Turkey (sections 13-16) were grouped separately at the beginning. The other categories appeared disorganised at first glance. However, after studying them, it became clear that the majority of these Sections were organised roughly by geographic location – Athens and Attica, Peloponnese, Northern Greece, the Islands, Cyprus, Asia Minor, etc. Within these Sections were a mixture of maps with different dates and some maps in series were kept together if they all fell within the specific geographical location defined by the Section. There was also a smaller group of maps classified by historical or by geoscientific themes.

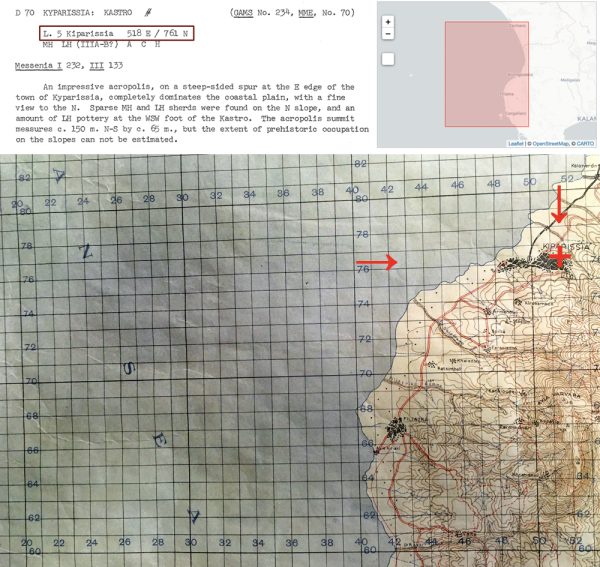

It seems that geographic location was the primary concern in Boardman’s categorization, an organisation system that facilitated archaeological work. Keeping the British WWII staff maps up front was also significant. Before the last decades of the 20th century with the availability of detailed Greek army maps and the introduction of GPS, British staff maps were considered the best means to locate sites. For example, British staff map coordinates in the form of E and N grid references were used by Hope Simpson in his gazetteers, by David French in his study of material from Central Greece and Macedonia, and by Hugh Sackett in organising the BSA sherd study collection when he was Assistant Director (1962-1963).

Gazetteer entry from Hope Simpson & Dickinson (1979) with map coordinates highlighted, Section 7, No. 18. 1:100,000 Greece Sheet L.5 Kiparissia: coverage in Digital Collections, and detail of site location on the map.

Analysing this organisation system shows how maps were considered tools of the archaeologist’s trade. The emphasis was on geographic location and the ability to locate archaeological sites within the landscape. The geological maps were also considered to be useful for determining the source of raw materials used in ancient structures or in the production of artefacts, particularly pottery. In fact, a larger collection of geological maps is held by the BSA’s Fitch Laboratory (established after Boardman’s time as Assistant Director) with this type of scientific research in mind. It should be noted that many of the older maps preserve obsolete place-names and toponyms which are also helpful in locating places where names have changed.

Part II: How to Lie with Maps

With the advent of digital cataloguing it became possible to categorise items in multiple ways while still retaining the original physical organisation of the material. While sorting maps in the BSA collection and integrating the Rare Maps, I organised them virtually by issuing agency and date, and by keeping specific series together (a pdf of this classification is available on the BSA Library web-page). Ordering the maps this way allows us to see them in historical context. A few aspects of early Greek history (from 1826 to 1923) are discussed below through maps (and their stories) in the BSA collection.

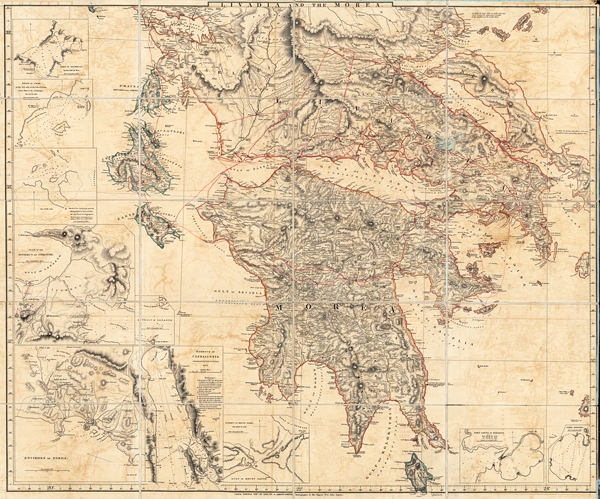

In the BSA’s George Finlay collection there are a number of maps, many dating to the early decades of the 19th century. Finlay was a Scottish Philhellene and historian of the Greek War of Independence, a keen observer and recorder. One of his maps dates to 1826, probably a replacement sheet for a section he lost from an original 1819 set (Greece and Adjacent Countries with Modern and Antient Names) by the British map publishing company founded by Aaron Arrowsmith, noted geographer, cartographer and hydrographer. Arrowsmith established himself as one of the premier British map makers in the late 18th century, producing maps of many places across the globe. His sons and later his nephew continued the company into the 19th century, producing maps, atlases and geographical texts. Because of the vast range of the maps and atlases the company produced, it is likely that Arrowsmith’s maps were created in the traditional way by using the most recent cartographic data available from a variety of sources, and adding routes and place-names culled from travellers’ reports. In effect, this was a standard commercial map that Finlay purchased, initially the 1819 edition, with an updated version in 1826. What makes the map below unique are the annotations, possibly added by Finlay himself, to show his travel routes, marked by red and yellow lines. It is interesting to note that Finlay’s routes include little “spurs” off the main routes that lead to sites of archaeological interest – such as the “ruins” (Mycenae) en route from Argos to Corinth. Generally, however, these alterations to the original map demonstrate the great distances covered and extensive number of places he visited: Peloponnese (Morea), Ionian Islands and across the Gulf of Corinth (Gulf of Lepanto) into Central Greece (Livadia), reminding us that Finlay was an eyewitness to many events of the war.

Rare Map Collection D 3.1: Greece and Adjacent Countries with Modern and Antient Names by A. Arrowsmith: Livadia and the Morea (Finlay Collection)

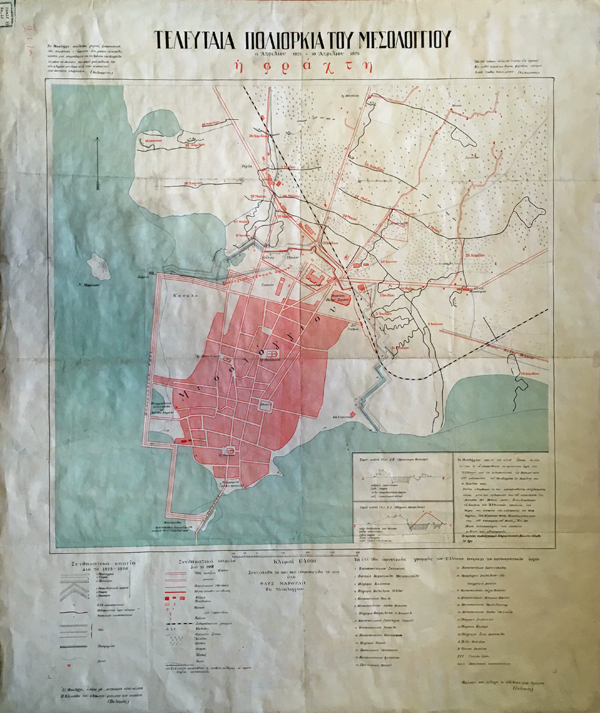

One of Finlay’s travel points, shown in the map above, was Messolonghi, perhaps as a jumping off point en route to Zakynthos (Zante) or Cephalonia. Messolonghi was a significant place in the War of Independence, not least as the first place in Western Greece to join the uprising in 1822 or as the place of Lord Byron’s death in 1824, but primarily for the last or third siege of the city by Ottoman forces. This last siege of Messolonghi lasted from April 1825 to April 1826, resulting in starvation and spread of disease, and ending with a disastrous attempt to flee the city – the famous exodos – leading to slavery or death. Although militarily a defeat, the sacrifice became a focus of Western sympathy and eventual practical support for the Greek cause. The map below was produced in 1926 at the centenary of the siege. The mapmakers marked the fortifications (ή φράχτη / “the fence”) and the Ottoman lines of approach superimposed on the current plan of the city, a reminder that the past is part of the present. This map is a piece of commemorative memorabilia, a prompt to sustain collective memory of an event, particularly significant if that event is no longer within living memory.

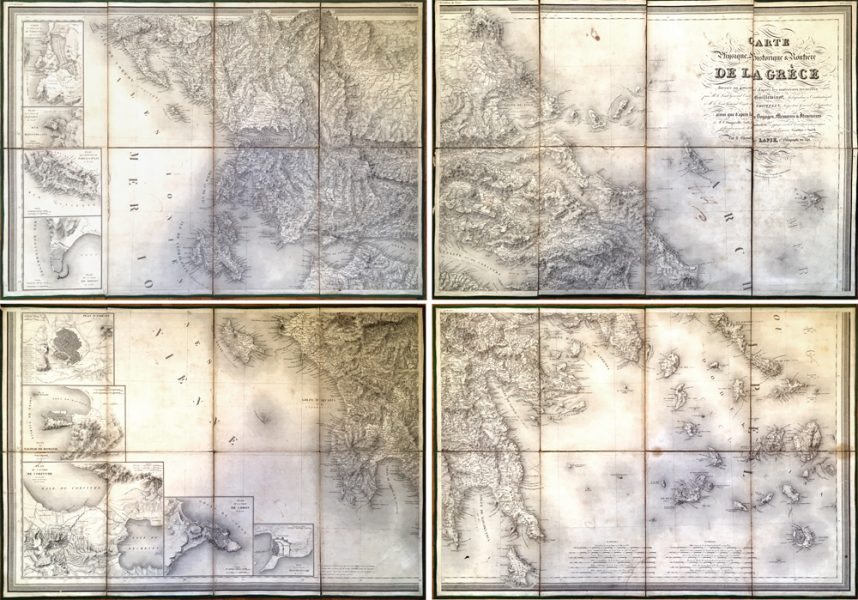

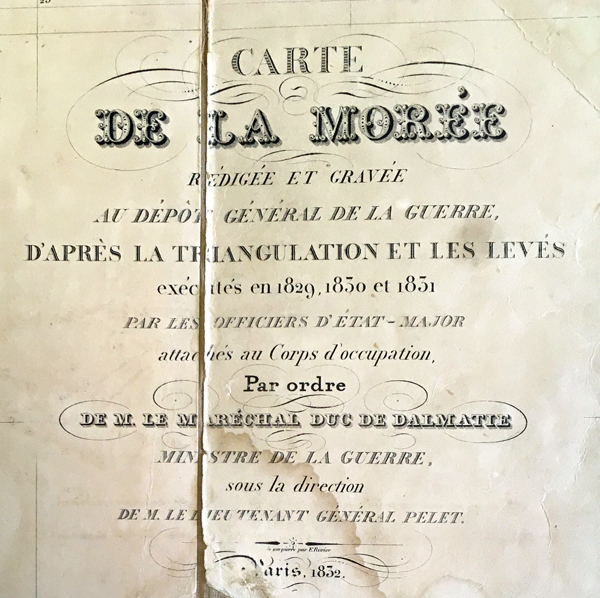

French maps were used by Greek forces during the War of Independence, including those by Pierre Lapie. Lapie produced maps in 1822 and again in 1826 which were created in the traditional method by using travellers’ reports and point-positioning of latitude and longitude. Illustrated below are the four sheets that make up his 1826 Carte de la Grèce which shows less area than the original 1822 map of southeast Europe, focusing more on the need for cartographic support during the war, as indicated by Livieratos (see Mapping Greece in the 19th Century). However, it was the first Governor of the modern nation of Greece, Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, who – as part of his administrative concerns in organising a new state – initiated systematic mapping of relevant territories (see Livieratos 2009, 2011, 2021 and Ploutoglou et al. 2011). At Kapodistrias’ invitation, the French Army and their chief cartographer, Jean Pierre Eugène Félicien Peytier, produced the Carte de la Morée from 1828 to 1831 (published in Paris in 1832) as part of the scientific mission Expédition de Morée. This was the first scientific mapping of the area based on geodetic cartography (i.e. survey that allowed for the earth’s curvature). Unlike Lapie’s map, the coverage of the Carte de la Morée is restricted to the Peloponnese (Morée or Morea). The French military, again under the guidance of Peytier, would not extend their geodetic cartography to match the coverage of Lapie’s map until 1852 with the publication of their twenty-sheet series, Carte de la Grèce.

According to George Finlay in his History of the Greek Revolution, Kapodistrias’ handling of government was held in contempt by so many factions that it led to his assassination in 1831. The following year, at the London Conference of 1832, the Great Powers (Britain, France and Russia) established the first Regency of Greece and offered the throne to Otto, second son of King Ludwig of Bavaria. That same year, before Otto set foot on Greek soil, the publisher Johann Georg Cotta in the Bavarian city of Munich produced the Charte von dem Koenigreiche Griechenland, Map of the Kingdom of Greece, perhaps unconsciously stamping it with a pride that the new Kingdom hailed from Bavaria. The BSA Map Collection holds an 1834 edition of this map with the border of the new Kingdom marked by a blue line. Its sub-title is in smaller print: nebst Theilen der angraenzenden Laender des Osmannischen Reiches in Europa und Asien nach den neuesten Grenzbestimmungen herausgegeben which translates as “together with parts of the bordering countries of the Ottoman Empire in Europe and Asia according to the latest border regulations”, implying that the borders are not immutable.

Section 29, No. 11: 1834 Charte von dem Königreiche Griechenland, Bavarian map of the Kingdom of Greece

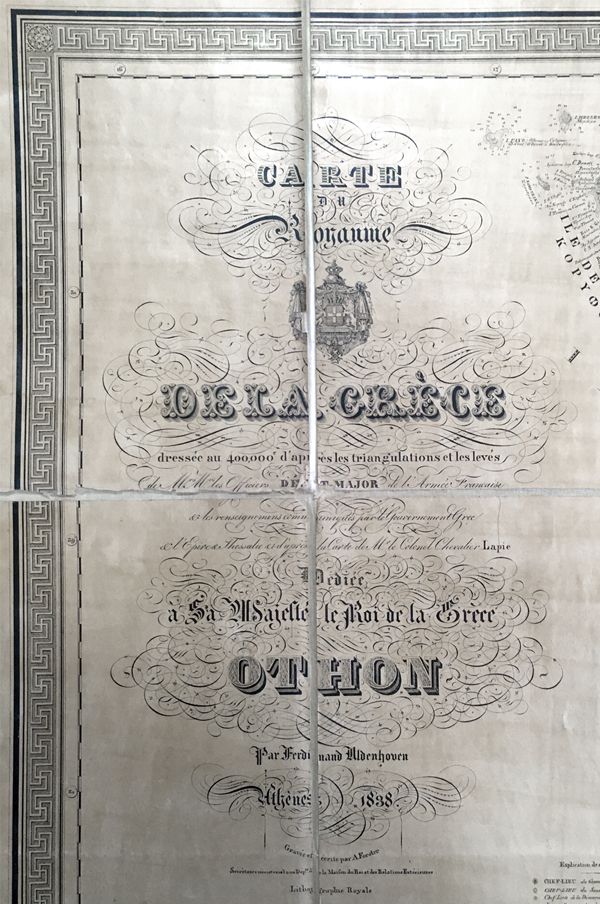

A few years later, in 1838, the German mapmaker, Ferdinand Aldenhoven created a similar map which he based on maps by Lapie, the French military, and the British traveller and cartographer Col. William Leake. Aldenhoven dedicated his map to King Otto and prominently displayed the Hellenised version of the King’s name and his crest on the map (in both French and Greek titles). Aldenhoven also stressed the Royal link by publishing it in the Royal lithographic printing house in Athens and by using the word Royaume in the French title and ΒΑΣΙΛΕΙΟΥ in the Greek title. In addition, the map is of grand proportions, probably designed as a wall hanging, and contains a decorative Greek key pattern border and elegant calligraphy in the titles – all designed to aggrandize it. Like the 1834 Cotta map above, the coverage of Aldenhoven’s map showed areas outside of the current territory of Greece – Crete, Thessaly Epirus, Macedonia, the Ionian Islands and the coast of Asia Minor. The depiction of these areas, no doubt, reflects the aspiration to expand the initial territory of the kingdom, explained by Livieratos (see Mapping Greece in the 19th Century). It is no coincidence that the term Megali Idea or the “Great Idea” first appeared during Otto’s reign in the 1840s, recognising a pre-existing irredentist vision to liberate areas dominated by Greek-speaking populations from Ottoman rule, in effect restoring the territorial extent of the Byzantine Empire.

Rare Map Collection D 2: The French title on the Aldenhoven 1838 map Carte Royaume de la Grèce (Finlay collection)

Skipping forward some decades, the map below dates to 1896, just one year before the Greco-Turkish war of 1897. It shows Greek territory extended in the north due the annexation of Thessaly, one of the concessions of the Berlin Congress of 1881, although the larger issue of borders remained unresolved. In the upper right corner are the portraits of the Royal family – King George I and his wife Queen Olga above, with Crown Prince Constantine and his wife Sofia below – perhaps reflecting an esteem held for the family. It was Constantine who led the forces in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, the first time that the Greek military was put to the test against the Ottoman Empire in a declared war since the War of Independence.

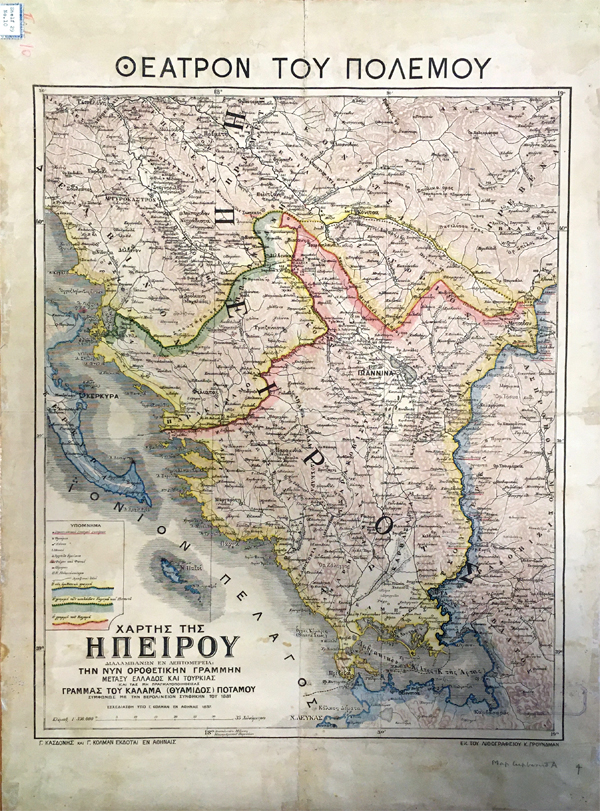

Initially the primary concern during the war of 1897 was support for the uprising in Crete, but when Greek forces were unsuccessful in annexing the island, they made an ill-fated attempt to confront occupying Ottoman forces in Thessaly and Epirus. The war lasted a little over a month and resulted in Greece ceding some territory along its northern border and agreeing to monetary reparations. Another consequence was the loss of confidence in the Greek army and the Royal house. The Greek map below dates to 1897 and shows Epirus from the current Greek-Ottoman border (blue) at Arta to “unrealised” territories north beyond Ioannina along the Kalamas River (pink) and the Kalamas valley to the Pindus (green) “according to the Berlin Treaty of 1881” as mentioned in the map’s title. The entire area is simply labelled ΗΠΕΙΡΟΣ (Epirus) and only mentions Greece and Turkey in small print in the title. This seems to be a martial expression of the unresolved border issues of 1881.

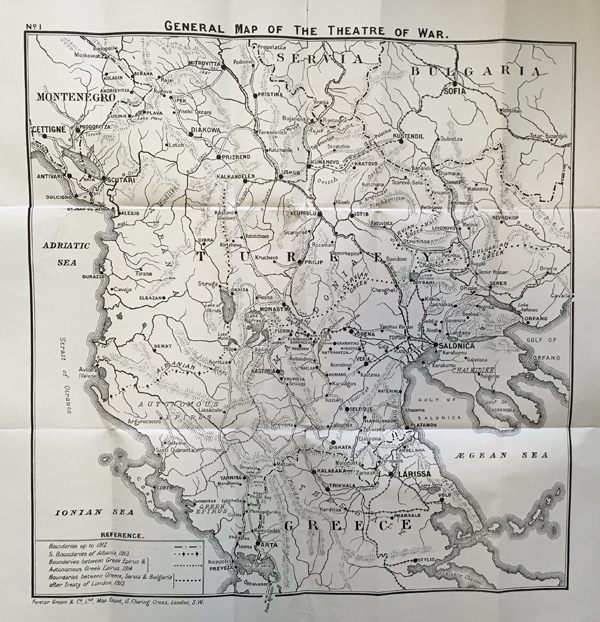

The First Balkan War (1912-1913) reversed the 1897 defeat. It saw the Balkan League (Serbia, Greece, Romania and Bulgaria) defeat the Ottoman Empire with Greece gaining territory in Epirus, Southern Albania, Macedonia and many of the islands along the coast of Asia Minor. The second Balkan war was a dispute between Bulgaria and the remainder of the League on the division of Macedonia. The map below was designed for the British audience which was observing the growing instability in the Balkans and was concerned with the international ramifications – which ultimately led to WWI. It was published in 1914 by Stanford, a well-known map publisher based in London. Although the map mimics the 1897 Epirus Theatre of War map, this one specifically marks the location of Turkey and Greece and dispassionately illustrates the facts of the boundary lines in 1912 and the new ones in 1913/1914.

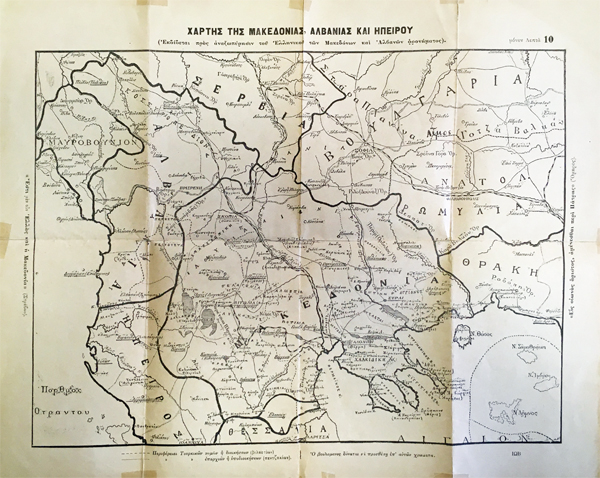

The undated Greek map below probably dates to a time prior to the Balkan Wars since the dotted and dashed lines on the map refer to divisions of Ottoman territories (Vilayets and Sanjaks) which extend into Epirus and Macedonia. On the reverse of the map is a pencilled notation, “Greek propaganda map”, probably written at some time after the map came to the BSA. The quotes from ancient authors along the left and right borders reveal the map’s intent. The left side reads “«Ἔστι μὲν οὖν Ἑλλὰς καὶ ἡ Μακεδονία» (Στράβων)” from Strabo’s Geography, Book VII where the Loeb translation has “Macedonia, of course, is part of Greece”. The right side is from Homer, “«Εἶς οἰωνὸς ἄριστος, ἀμύνεσθαι περί Πάτρης» (Ὄμηρος),” Iliad XII, which translates as “This is the best omen, to fight for your country”, ironically spoken by the Trojan Hector. It clearly points to Greek territorial claims and a patriotic justification to fight for the land. Interestingly, the notation at the bottom of the map instructs Members of Parliament to add colours to the map.

The ideology of the expansion of the Greek state embodied in the Megali Idea, according to Livieratos was “fuelled by growing ethnographic ideas and relevant mappings” (Mapping Greece in the 19th Century). The prominent German cartographer, Heinrich Kiepert, produced an ethnographic map of the Balkans in 1882 based on the distribution of languages. What it shows is the dominance of Greek (blue) over the southern peninsula, Crete and the majority of the islands. Cross-hatching is used to show an admixture of Albanian (green) and Greek just to the northwest and Turkish (pink) and Greek to the northeast – extending to Istanbul (Constantinople). Further north there are more homogenous Slavic, Bulgarian and Romanian speaking areas.

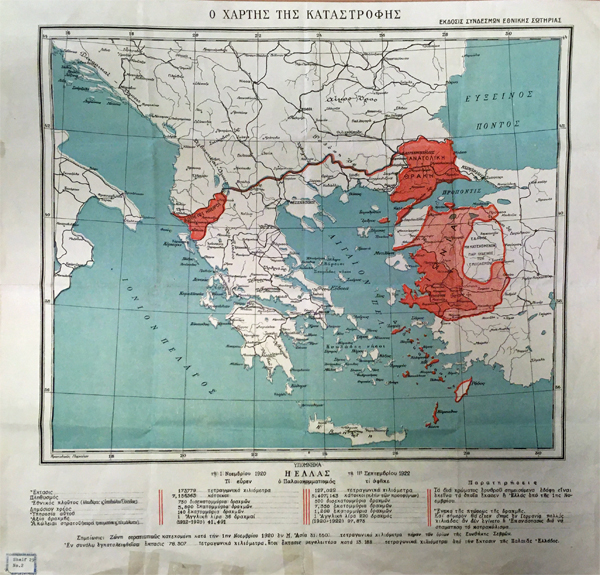

The ultimate expression of the Megali Idea was the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922. It was a clash between Greece and the Turkish National Movement (under the command of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk) in the wake of the post-WWI partitioning of the Ottoman Empire. The aim was to restore Greater Greece on both sides of the Aegean and return Constantinople to Greek hands. The Greek forces made incursions in Thrace, Epirus (southern Albania) and into Anatolia (starting from Smyrna, modern İzmir). With the intervention of Italy, France and Britain, hostilities ended with the Armistice of Mudanya in October of 1922. The 1922 event was known in Greece as the Καταστροφή (Catastrophe). Greece lost much of the territorial gains it made as shown in the Greek map below. The map does not show the human suffering and atrocities committed. Instead, it focuses on more measurable statistics. The text below the map simply lists numerical data in columns for 1920 and 1922: territory in square kilometres, population (excluding refugees in 1922), national wealth, public debt, (cost of) servicing the debt, the value of the drachma and military losses.

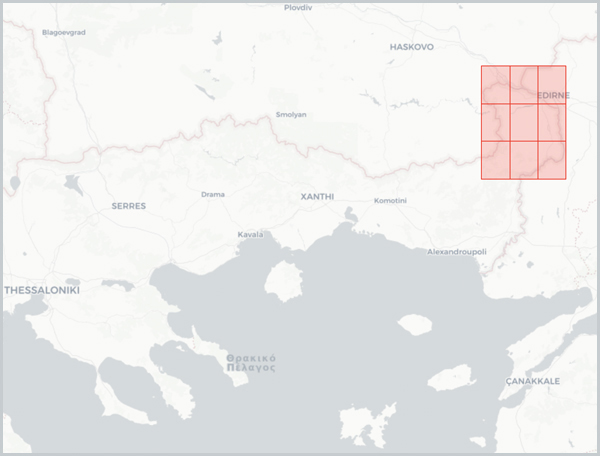

The Treaty of Lausanne officially settled the territorial conflicts, resulting in the population exchange and the massive influx of refugees into Greece. Another consequence was establishing the border in Thrace, the division of the old Ottoman Vilayet of Adrianople (modern Edirne). The treaty was signed in July 1923 and came into effect the following year. As a response, and as a way of defining and controlling territory, the Greek military geographical service (Χαρτογραφική Υπηρεσία Στρατού, later changed to Γεωγραφική Υπηρεσία Στρατού) surveyed an area which marked the boundaries between Eastern and Western Thrace along the Maritsa (Evros) river. The map series produced has nine conjoining sheets covering the Evros area, a section of land north of Alexandroupoli with Turkey to its east and Bulgaria to its west. The series is stamped with “έκδοσις εμπιστευτικός” (confidential edition), standard on Greek military maps. Significantly, the series dates to March 1923, at least four months before the treaty was signed.

Section 22, No. 6 to No. 14: Adrianople 1923 map series distribution shown on BSA Digital Collections

Presented here are only a few possible map stories. There are more stories to explore in the collection such as that of British Imperialism and hydrography in the Mediterranean based on the 19th century British Admiralty charts (Sections 9-12). The set of field maps of the Macedonian front (Section 21) tell the story of active WWI engagements. The maps clandestinely produced by British intelligence service from 1901 to 1919 (Sections 13-16) tell of British military information gathering in the Ottoman Empire before, during and immediately after WWI. Many of the 19th-century Austrian staff maps and the early Greek army maps elucidate the history of military cartography in Greece. The 1934 map series of the Survey of Egypt (Section 40, Nos 1-4) and the 1931 Carte Internazionale dell’ Impero Romano: Roma (Section 40, No. 5) coupled with the pamphlets of the International Map of the Roman Empire (Rare Map Collection C 32 – C 34) tell the story of the ambitious project, initiated prior to WWII, to chart the fullest extent of the ancient Roman world (Tabula Imperii Romani). More maps, charts and historical atlases that concentrate on ancient sites and territories reflect the reception of the ancient world in the 19th and 20th centuries. And aspects of tourism research are revealed in commercial tourist maps. In other words, teasing out conscious and unconscious decisions show us there are multiple ways of seeing and multiple stories to tell.

Deborah Harlan

British School at Athens

The BSA Map Collection is catalogued on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

A pdf of the BSA Map Collection is available on the BSA Library web-page.

Click here for more BSA Library Stories.

Further Reading:

Finlay, G. (1861) History of the Greek Revolution. 2 vol. Edinburgh: Blackwood and Sons

French, D. (1967) Index of Prehistoric Sites in Central Macedonia and Catalogue of Sherd Materials in the University of Thessaloniki. Unpublished manuscript.

French, David H. (1972) Notes on prehistoric pottery groups from central Greece. Unpublished manuscript.

Hope Simpson, R. (1965) A gazetteer and atlas of Mycenaean sites. London: Institute of Classical Studies.

Hope Simpson, R. and Dickinson, O.T.P.K. (1979) A Gazetteer of Aegean Civilisation in the Bronze Age, Vol. I: The Mainland and Islands. Göteborg: Paul Aströms Forlag.

Livieratos, E. (2009) Χαρτογραφικές περιπέτειες της Ελλάδας 1821-1919. Athens: ΕΛΙΑ-ΜΙΕΤ.

[For a brief synopsis, see the web-site: Mapping Greece in the 19th Century.]

Livieratos, E. (2011) ‘A New View on the French Cartographic Mapping Footprints in the Early Life of the New Greek State (1827-1834)’, in the 25th Annual International Cartographic Conference, Paris.

Livieratos, E. (2021) ‘Geospatial challenges of the Revolution: the visions, the lands, Kapodistrias’ utopia, the borders, the French cartographers and the subsequent chronic confusions of the state (until today?)’, in. the ‘1st Forum of Diplomacy’ Conference, Kalamata.

Monmonier, M. (1991) How to Lie with Maps, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ploutoglou, N. et al. (2011) ‘Two Emblematic French Maps of Peloponnese (Morée): Lapie’s 1826 vs the 1832 (Éxpedition Scientifique). A Digital Comparison with Respect to Map-Geometry and Toponymy’, in the 25th Annual International Cartographic Conference, Paris.