First Adventures in Revolutionary Greece: Fiction or reality, and does it matter?

In my previous Archive Story, Philhellenism redux- Finlay rises, I sought to shed some light on how George Finlay, and some others like him, decided to join the Greek revolution. In doing so, I drew on a note that Finlay wrote about himself and sent to C.C. Felton in the early 1860s. Indeed, as I argued in that note, human motivation is always difficult for the historian to grasp, and it is always helpful when these ‘actors’ offer, to those like me who come later asking questions, their own versions of events or their life-course. But to what extent can we rely on these personal accounts to answer our historical questions? Are we to take them at face value? Was George Finlay of the 1860s true to George Finlay of the 1820s? Besides, events such as revolutions are usually deeply dramatic and transformative events. They transform lives (bandits, or pirates become revolutionaries and then respectful statesmen); they transform space (countries are born, as in the case of Greece, others are lost); they transform words (the word revolution acquired a new meaning with the advent of the French Revolution, the word Σύνταγμα, i.e. Constitution, entered the Greek vocabulary); they transform objects (consider a national flag, or the foustanella that acquired the symbolism as a national costume which continues today). In that sense, accounts of the time have to be taken with a grain of salt and read critically, and against the historical record. They also have to be read with an eye for the rhetorical trope they employ and, probably more crucially, for the time of their writing.

Interestingly enough, Finlay himself seems to have been aware of all this. All good writers and, in particular, historians usually do. Indeed, if one reads one of his early writings on the Greek revolution and his first days in Greece, she/he is left wondering whether this is a piece of fiction or something drawn from Finlay’s actual experience. Certainly, the story it tells is so anecdotal and written in such a way that it reads like fiction. It contains a lot of traveling, changes of fortune, a robbery, some assassinations, attempts at assassination, a trial and some executions. At the same time, the author presents it as a first-hand account of his first months in Greece. Interesting times, to say the least. But let’s take things from the beginning…

The article is called ‘An adventure during the Greek Revolution’ and was published in the Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in November 1842 (vol. 52, no. 325, pp. 668-73). A copy can be found in Finlay’s collection at the BSA, within a volume (FIN/GF/E/38) that contains Finlay’s letters and printed articles (with some handwritten addenda and corrigenda). As my colleague, 1821 Archive Project Assistant Felicity Crowe, showed in her last Archive Story, O! Sycophant!, Finlay’s papers are full of annotations. But, interestingly enough, this even goes for his own printed articles. Indeed, he seems to have been taking notes and correcting even himself—a grumpy old man, maybe, as Felicity wrote, although not sure he had to be old to be grumpy.

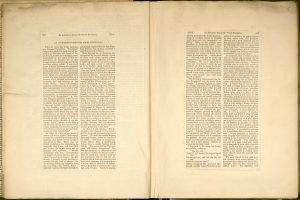

The first two pages of George Finlay’s copy of the article published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, FIN/GF/E/38

Now, back to Finlay’s ‘Adventure’…which according to him began before the Greek Revolution. The story actually starts with some interesting observations on the semantics of the revolution and on the social groups that showed a strong interest in it: ‘The Greek insurrection excited a good deal of attention at the time’ writes Finlay, ‘and many of the professors, as well as the students, were enthusiastic in the cause of the regeneration of Greece, for so the struggle between the Greeks and the Turks was then always called.’ Immediately then one is confronted with the saga of the Greek Revival that associated ancient Greece with Western civilization and the Greek Revolution with the chance of repaying that age-old debt now that the Greek subjects of the Ottomans had broken their bonds with the latter. It was to such calls that the international volunteers responded.

But this notion of ‘regeneration’ was much more widespread at the time and did not concern only Greece. In fact, one common feature of the revolts across the Mediterranean in the 1820s was the reference to past (and fallen) greatness—one that the revolts sought to regenerate. In the case of Spain and Portugal- that harked back to their imperial past. Italians and Greeks harked further back in time, to the great days of Rome and Greece (but also Egyptians to Egypt etc.). Indeed, the nineteenth century saw these histories of past greatness probed and scrutinized – sometimes with the aid of advanced British, French, and German scholarship. No wonder then, as Finlay points out, among the first to respond to this regeneration calls were students and other young educated men in Western Europe.

Finlay was studying in Germany (in Göttingen), so it is German universities, in particular, he has in mind here. He immediately responds with acerbic remarks about these German students who first went to Greece and came back telling their stories: ‘They had invariably lost every spark of enthusiasm, and uttered dire lamentations over the ingratitude of the Greek race’, as they [the Germans] had ‘(…) absurd expectations of becoming heroes in six months, or rich men in six weeks (…). For Finlay that was no surprise, as a ‘German who goes abroad to make his fortune is always far more impatient and insatiable than any other adventurer.’ Thus, for Finlay, the Philhellenes, at least the early ones, were adventurers – a term that Lord Byron actually used to designate that motley crew of foreigner volunteers that he met from the moment he set foot on the revolutionary Greek mainland. As Roderick Beaton has argued, Byron’s account highlights the many divisions within this motley group of volunteers, the tide of which swelled during 1822. Although most of them were willing to fight, few were trained soldiers or officers—most were merchants, students, cobblers, tailors, cart-repairers, butchers, doctors, clerks, and domestic servants. It would be later on, in 1826, when the future of revolution hung in the balance, that an equal size of volunteers, very different in nature this time, would come to help the Greeks.

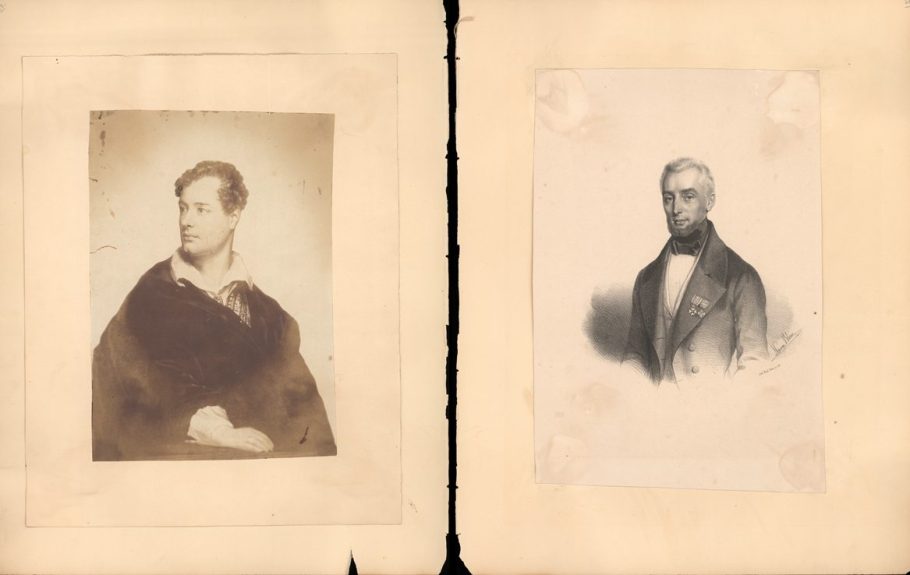

Lord Byron (left) and George Finlay (right), FIN/GF/20 (p. 83-84)

But Finlay was different, or, at least, that is what he believed. ‘The fancy struck me’ he says, ‘that the Greek Revolution would afford any one, who could venture to live in the tumult, an interesting view of history as it is represented in the reflection of historian’s mind’. This is an important point, as Finlay seems to be saying that the Greek revolution drew the historian out of him. More crucial is probably the self-perception it provides. Writing this piece in 1842, Finlay seems to be thinking of himself as a historian long before he started writing actually history.

The interesting points continue, because what does a historian do, according to Finlay, when he is interested in a topic? First, he acquires ‘some knowledge of the language and the habits of the people.’ Then he visits the place and lives with the people that inhabit it. Do we have here a historical ethnographer avant la lettre? This seems to be the case. Although, we will have time to look into this in more detail in the future, suffice it to say here, that in fact, Finlay would hold to this vision of the historian’s craft for years to come. And no matter how one sees his historical accounts, it is undeniable that Finlay remained one of the keenest observers of all things Greek and in particular of Greek customs and habits throughout his life. His voluminous collection at the BSA testifies to that. Maybe this is why he tried somewhat incessantly to stand in an ambiguous position in Greece, as a sort of a ‘participant observer’ who was ‘in-between’ Greek culture and his own. Indeed, although so present in Greek public life, he remained to an extent a foreigner—an ‘Englishman’ (even though he was a Scot).

Manuscript letter of Ephorate of Athens Archaeological Society to George Finlay (27 March 1861) thanking him for antiquities presented to the Society’s museum, FIN/GF/A/20 (p. 91-92)

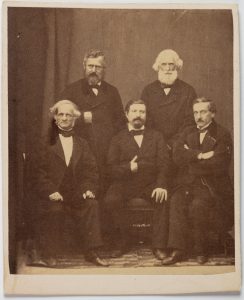

George Finlay (back right), with a group of men in Athens (among whom is Alexandros Rizos Rangavis (front left), FIN/GF/A/20/1

Back to 1823. That he came to Greece with an eye for the ethnographic detail should not surprise us. This was the era of the great scientific expeditions in the Eastern Mediterranean (French and Russian); the period when the region at large became integrated in the large processes of modernity. And as we know, knowledge production was a crucial aspect of this integration. That this knowledge was a product and an imperative of imperial expansion is also something we know in depth. That is not to say of course that Finlay came as some sort an imperial agent. But it is to say that this ethnographic interest and ‘gaze’ was primarily generated in those counties that occupied the higher echelons in the civilizational standard of the era – unexpectedly these were the imperial powers of the era.

Surely, Finlay would hold a critical attitude towards empire. But he preserved this ethnographic ‘gaze’ on the Eastern Mediterranean until the end of his life, as evidenced by his accounts and journals on his travels in Greece, Anatolia, the Middle East and so on and so forth. Interestingly enough, in the article, Finlay tells us that this interest was well established in 1823 before he joined the Greek Revolution. But could it be that this interest was the outcome of his revolutionary experience? That it was the unanswered questions that the revolution generated in the young student’s mind, as well as his anxiety to answer them, that directed him to this ethnographic ‘gaze’? Ethnography may have had imperial roots, but it could also lead its practitioners to raise scathing questions about empire.

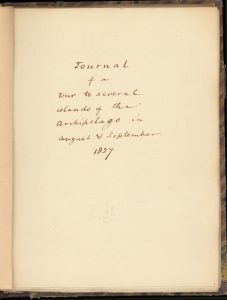

First page of, ‘Journal of a tour to several islands of the archipelago in August and September 1837’, FIN/GF/A/10

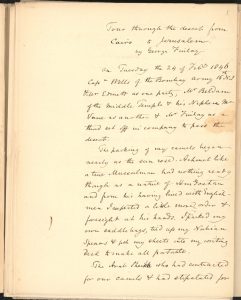

First page of, ‘Cairo to Jerusalem. Jerusalem to Dead Sea and Beyrout’, FIN/GF/A/11/2

Besides, ethnography, just like all good stories need good characters and good settings. Finlay’s stories usually have both. An important character in this ‘adventure’ of his was a certain Alecco, ‘a Greek at the University [of Göttingen]’, who was ‘silent, and his manners repulsive’. Finlay and the expatriate Greek start together the journey to Italy. They pass from Munich which ‘King Ludwig had not covered it [yet] with gilding and glory – nor had Lord Palmerston enriched its liberals with the peculation afforded by loans to Greece.’ In Venice Finlay meets ‘Caradja and Cantacuzene’ (two princes both related to the Mavrokordatos circle, the first more compared to the latter). Here, Finlay writes a quotation for the ages, as the two princes were ‘quarrelling bitterly concerning their respective pretensions to the sovereignty of the state which was to arise out of the Greek Revolution. I left them as they had almost resolved to sign a partition treaty: somebody advised to settle their quarrel in Greece by aiding the people, but both the princes agreed that Prince Soutzos would then overreach them both, for nobody can succeed, quoth the princes, who comes on the field too early in a revolution. I have since heard that these princes, Caradja, Soutzos, and Cantacuzene, all came too late, and did too little, to become great man in the land’.

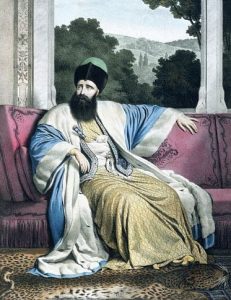

Michael Soutos (image public domain: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Soutzos)

The way to Greece for the two men was not very surprising: Rome, Naples, Bari, Otranto, where they embarked for Corfu. Due to some misfortunes, that he never specifed, Alecco asks Finlay to accompany him to Greece as his servant. Finlay agrees, noting that, in such conditions, master and servant lived under the same conditions. But they did not in any way become friends, as they did not ‘relish for one another’s wit’. But, they also never ‘had a difference of opinion or dispute’. In Greece, Finlay employed a soldier named Dimitri. In a way Dimitri, with whom Finlay ‘grew attached’, is the opposite of Alecco. ‘No gayer, braver, or more active man, ever breathed’, Finlay remarks. Could it be that Finlay describes here two ideal types of the Greek character as he saw them? Finlay did use such dichotomies in his writings—again something unsurprising for the age (if not for today).

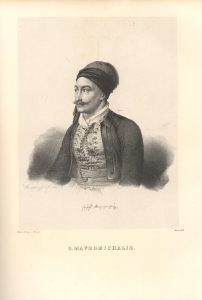

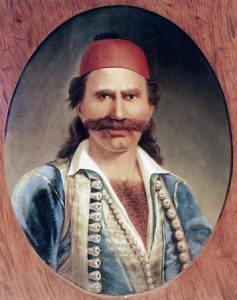

When he arrived in Argos, Finlay met a young Englishman called Abney. He stayed with Abney’s regiment, but, as he says, not as a soldier, but rather as ‘one who saw, observed, nor shunned the busy scenes of life, But mingled not; and ‘mid the din, the stir, Lived as a separate spirit’ –so, yet again, the observer. Soon he would stop being an observer and become prey. The cause was a portrait that Abney trusted to Finlay. The latter was to deliver the portrait, extremely value to Abney, to someone in Smyrna in order for it to reach London. In the next few days, both men were wounded in what initially appeared as an attack by Turks. But, it was quickly revealed, this was an attack by robbers who were after Abney’s portrait. After Abney succumbs to his wounds, Finlay is left with the task of executing his friends’ last wish. In trying to facilitate this, Finlay moves to Nafplion – in a house that not only Alecco finds but also insists that Finlay move in immediately, before Dimitri had time to accompany him. On Finlay’s first night there, the portrait is stolen. The next day Dimitri joins Finlay only to be sent away in pursuit of the portrait based on a lead that Alecco suggested. In the meantime, Alecco invites Finlay to dinner and also recommends a new and small Turkish bath for Finlay to visit, instead of the one he usually frequented. There the plot thickens, as Finlay writes, ‘the bath-keeper found an opportunity of seizing me by the throat, while I saw a woman enter with a dagger and a large towel.’…but he manages to escape. ‘The first person’, he meets, as he ‘rushed naked and bleeding into the street was George Mavromichalis’. This is the Mavromichalis who was going to be President of Greece at some point, and one of those who will be executed for the assassination of Kapodistrias in 1831. Having ‘always a kind and gallant heart’, Mavromichalis would lead a thorough investigation on the matter, only to reveal that ‘Alecco had planned the whole business.’ But Alecco had powerful friends. In the absence of Mavromichali from the city, the two assassins were swiftly condemned to death and immediately executed the next day. Alecco was trying to leave no traces of his actions and in so doing to bypass the due process of law. But what is crucial to highlight in this story is that, according to Finlay, there was a due process of law even amidst a rather messy affair as a revolution always is. Despite having these powerful friends, Alecco could only use them in trying to hide evidence and, in fact, witnesses.

Lithograph portrait of George Mavromichalis, FIN/A/20 (p. 27)

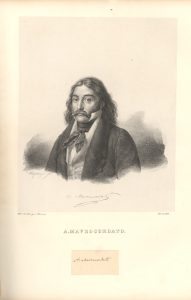

But there is more to this point, because it should act as a reminder that the conventional dichotomies that historians have used in order to explain the course of the revolution, and, in particular, that between traditional and modernising forces, lack interpretative force. Alecco, the educated student from Göttingen is the culprit in this story. And the one who turns to corruption. Mavromichalis, otherwise related to traditional political culture, is the one holding to the rule of law. But then the crucial question for Finlay is, in the face of abuse, how is justice to be served? For this, both he and Dimitri turn to Odysseas Androutsos, the warlord of Eastern Sterea also conventionally related to traditional culture.

Odysseas Androutsos (image public domain: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Odysseas_Androutsos)

After intercepting Alecco’s correspondence with Omer Vrioni, Finlay and Dimitri reveal his treason to Odysseas, who condemns Alecco to death ‘in a very summary manner’ and has him executed. And, as Finlay says, ‘a satire, I suppose, both on the classic and romantic schools of thought, for Odysseus detested equally Maurokordatos and Colettis’. Fiction, a testimony, or something in-between, what the Greeks call μυθιστορία? I think that, through this story, Finlay is commenting, in his own way, on the political history of the revolution. One that he sees as beginning in 1821 but continuing to the day of writing this article (1842). In Finlay’s understanding, during the revolution different ideas about justice and its administration were expressed. Limiting these ideas to a contrast between traditional and modern/progressive forces seems, if we follow Finlay, to be missing the point. Because Finlay seems to be telling us that what is just, does not always equal with what is right. And that justice could be served (for better or for worse) when respectable local people are involved. Last but not least, Finlay is also probably telling us that the revolution had not exactly ended at the time Finlay wrote and pubished the article. Indeed, in 1842 and for many years after that, two persons dominated Greek politics (apart from King Otto): Mavrocordatos and Colettis.

Lithograph portrait of Alexandros Mavrocordatos, FIN/GF/A/20 (p. 19)

Coloured lithograph portrait Ioannis Collettis (Adam Friedel, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr Michalis Sotiropoulos

The 1821 Fellow in Modern Greek Studies

British School at Athens

For more information on this BSA research project, visit the dedicated webpage, Unpublished Archives of British Philhellenism.

V