Fragmented Archives: an Example of the Photographs of J.A. Spranger in the SPHS Collection

How are archives formed? I’ve noticed that archives are incomplete by nature – winnowed from their original “core” – a representative of the whole. Selection of what is preserved may be intentional or arbitrary. In some cases, collections have been split up and dispersed, fragments ending up in a variety of archives. Photographic collections present yet another layer of diffusion: photographs can be reproduced, creating the possibility of multiple versions in multiple formats occurring in a multitude of places. Yet, to help us reconstitute the whole, there are often “paper trails” providing us with clues to how these incomplete, fragmented archives came to be the way they now are.

As a collection of photographs, the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS) Photographic Library was formed in the late 19th century (see Archive Story: Rule II), continued to be added to, and used for lending or duplicated for purchase by the society’s members until the mid-20th century. During the decades it was in use, according to the marginalia in the photographic registers, some early images were replaced by newer ones and some simply went missing or were discontinued and removed. During its lifetime, the collection had been moved from location to location depending on where the headquarters of the SPHS was at the time and it can be assumed that the large collection of fragile glass negatives and lantern slides may have suffered attrition by breakage or simply by loss.

The diaspora of what remained of the original SPHS Photographic Library – negatives, prints, and lantern slides – happened in 2003 when the images were transferred to two institutions in Athens – the British School at Athens (BSA) and the Hellenic Literary and Historical Archive (MIET-ELIA). Prior to the dispersal, the majority of lantern slides were deemed unnecessary duplicates and are thought to have been destroyed. The BSA received thousands of negatives, a few hundred slides and prints on index cards. The BSA carefully chose images that had a close association to the BSA or were of topographical interest in areas the BSA was known to have worked – an intentional filtering. The remainder of the collection went to MIET-ELIA. At this point the material fossilised into distinct archives. In addition, original paper records (such as the SPHS photographic registers) and miscellaneous items (such as the William Stillman negatives) remained in London – either in the SPHS Administrative Office or in the Hellenic and Roman Library at University College London.

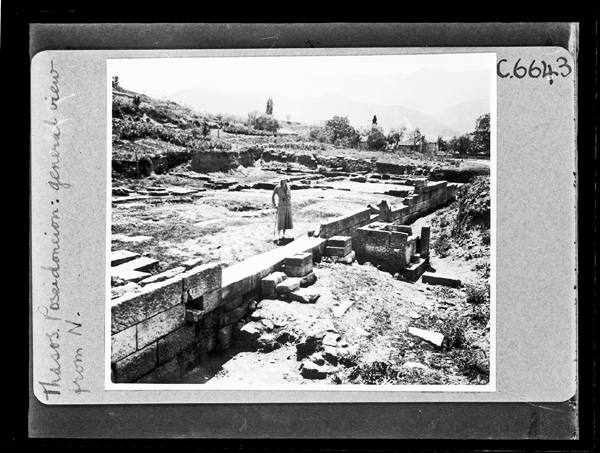

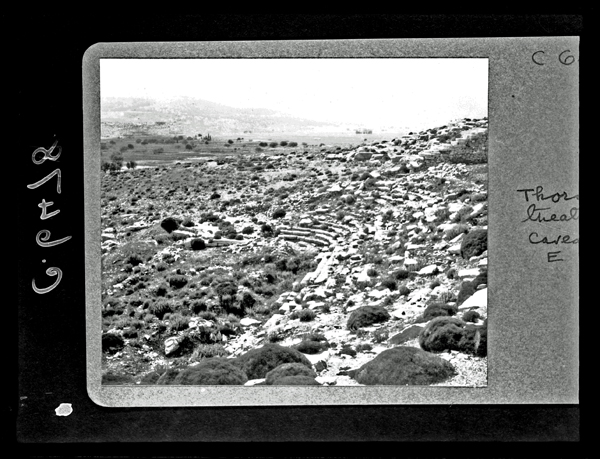

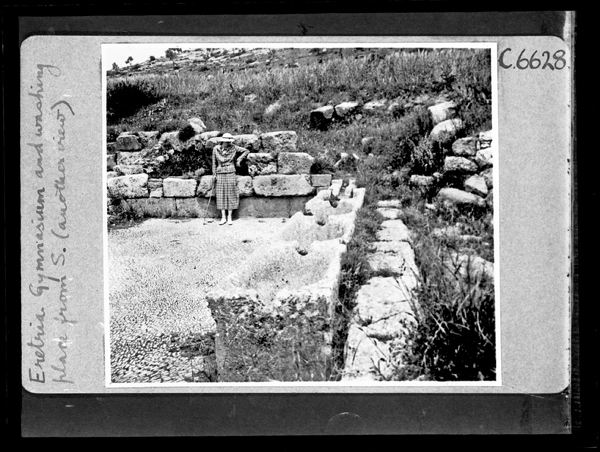

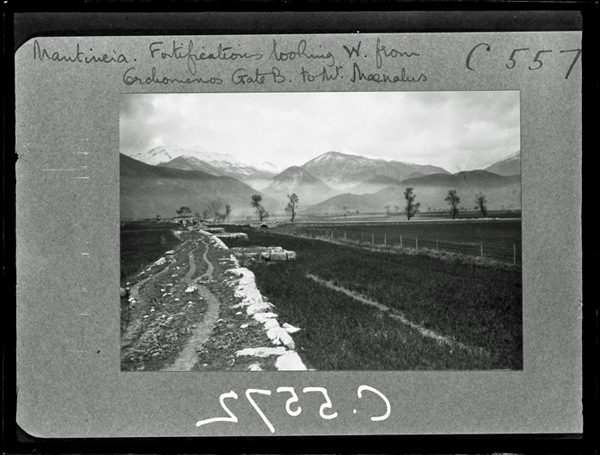

I’d like to take an example of a group of photographs within the SPHS collection, donated by J.A. Spranger, to illustrate the dispersal of material and how piecing together information from a variety of sources can help to fill out a a story. John Alfred Spranger (1889-1968), was born in Florence of a British family, educated in Britain, but spent most of life in Italy. He was a keen mountainteer, experienced topographer, trained mechanical engineer and photographer. His participation in the Italian Scientific Expedition to Karakorum 1913-14 as a topographer was thought to be the starting point in his fascination with documentary photography. In the early 1920s, he was an excavation photographer in Etruria and became a close friend to Harry Burton (who was noted for his photographic work at excavations in the Valley of the Kings). Spranger was also as an avid independent traveller to places in Italy, Albania, Greece, Canada, Iraq, and Egypt (where he visited Burton). Spranger’s archive is split between two Italian archives: the Centro di Documentazione Storico Etnografica (CDSE) based in the small town of Vaiano near Florence and the Photo-Archive of the Archaeological Museum of Florence which holds some photo albums of “archaeological subjects”.

During the interwar years, Spranger also made large donations of photographs to the SPHS, primarily depicting sites in Greece and surrounding areas (Southern Italy, Sicily, Istanbul and Asia Minor). There are 621 entries for images listed in the last two volumes of the SPHS photographic registers. However, the BSA SPHS collection has only 30 Spranger images despite having requested the entire set of Spranger images prior to the collection being transferred from the SPHS in London to the BSA. The discrepancy is larger than can be attributed to normal attrition that happens over time in the formation of archives. So, how can the difference in numbers be explained?

My first recourse was to examine the registers in more detail. The registers record data on negative size – small (size 1), medium (size 2) or large (size 3) – that roughly correspond to quarter plate, half plate or full plate negatives. Brief captions, the names of donors and columns to indicate the existence of prints and lantern slides are also recorded. In addition, the Spranger entries included his own cataloguing system by album and photograph number. Spranger’s images were recorded in four distinct groups, entered into the register as they came in to the SPHS photographic library, a possible indication that they were donated over a period of years. Groups 1 to 3 were primarily donations of prints with a few duplicated as slides and group 4 was a donation of slides with a few duplicated as prints. To confuse matters further, some of those donated in the last group were replacements for earlier donated images, although they were given new catalogue numbers.

The notion of multiple donations is confirmed by the slide accession lists published in the Journal of Hellenic Studies: group 1 in 1933, group 2 in 1935 and group 3 in 1936. The slide accession lists stopped being published after 1939. It is likely that the slides from Spranger’s last group may date the donation after 1939 since they do not appear in any published lists. Overall, these four groups of donations show that Spranger donated copies, not original media to the collection. It also provides us with a total of 745 objects (opposed to unique images) in the original collection in the form of prints, negatives and slides.

| Spranger Photograph Media Types by Group (SPHS registers) | |||||

| Group | 1: C5401-C5648 | 2: C6401-C6512 | 3: C6601-C6619 C6621-C6698 |

4: C7609-C7772 | Totals: |

| Prints | 248 | 112 | 97 | 44 | 501 |

| Slides | 22 | 12 | 6 | 164 | 204 |

| Negatives | 22 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 40 |

| Total Number of Objects: | 745 | ||||

A paper presented in 2019 by Nikos Koutsoumpos provided me with the final clue in resolving the disposition of Spranger’s donation to the SPHS. Koutsoumpos indicated that at least 362 Spranger photographs on SPHS index cards were held in the MIET-ELIA photographic collection. There are no prints of Spranger’s photographs in the BSA SPHS collection, only 30 quarter plate glass negatives from the first three donated groups – all of which the photographic register indicated had been duplicated as slides. The BSA negatives were likely produced as an intermediary stage to create slides from prints. Not surprisingly, all of these surviving negatives are copy negatives taken from small prints pasted onto the index cards – as you can see in the image of a negative below.

The number of Spranger photographs alone tells a partial story. However, by combining subject information from the BSA and MIET-ELIA archives along with the captions from the photographic registers, it is possible to assemble more pieces of the story. This information may shed light on Spranger’s perspectives on what he deemed relevant to donate to the SPHS – a decision that would fragment his own larger collection. We know from other sources that Spranger photographed other places (Egypt, Near East, Italy, etc). None of these photographs were deposited with the SPHS. Also, we can determine from the gaps in the sequence of his own album photo numbers that not all images from the albums are represented. The photographs in the SPHS collection were concentrated on locations in Greece, and in Sicily and Asia Minor – where there were Greek cultural remains.

| Spranger Images by General Location | ||

| General Area | Locations Represented | Totals |

| Attica | Athensº, Thoricos* , Rhamnous** º, Oropos Amphiareionº, Vougliagmeniº, Eleusisº, Sounion, Eleutheraeº, Aeginaº | 109 |

| Central Greece | Eretria* º, Delphi* º | 31 |

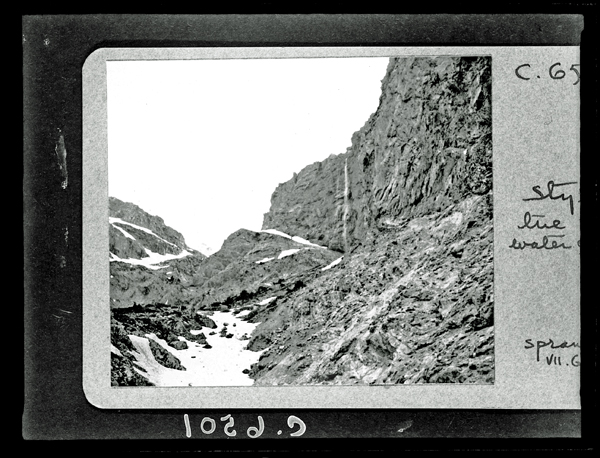

| Peloponnese | River Styx & Area*, Pylosº, Acrocorinthº, Corinthº, Bassaeº, Megalopolisº, Messeneº, Spartaº, Mantinea* º, Perachora* º | 50 |

| S. Aegean Islands | Rhodes* º, Thera* º, Delosº, Parosº, Melosº, Mykonos, Naxosº | 74 |

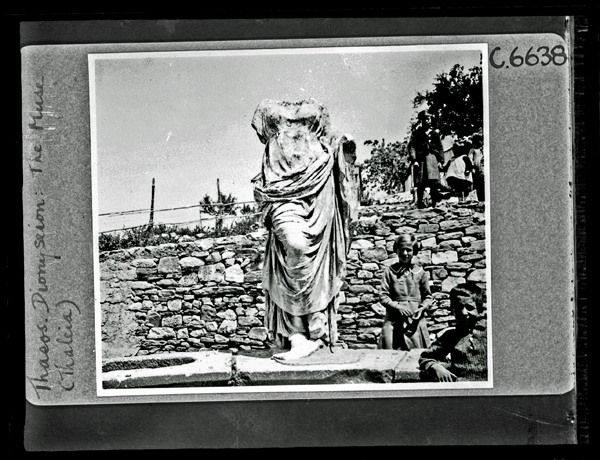

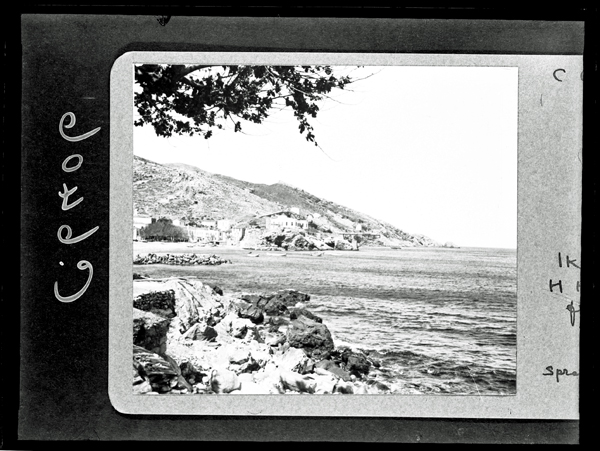

| N. Aegean Islands | Ikaria*, Thasos* º, Samothraceº, Lesvosº, Chiosº, Samosº | 104 |

| Ionian Islands | Kephalloniaº | 1 |

| Crete | Malia* º, Tylissos* º, Gourniaº, Priniasº, Knossosº, Nirou Khani Monasteryº, Gortynaº, Hagia Triadaº, Phaistosº, Praesosº | 113 |

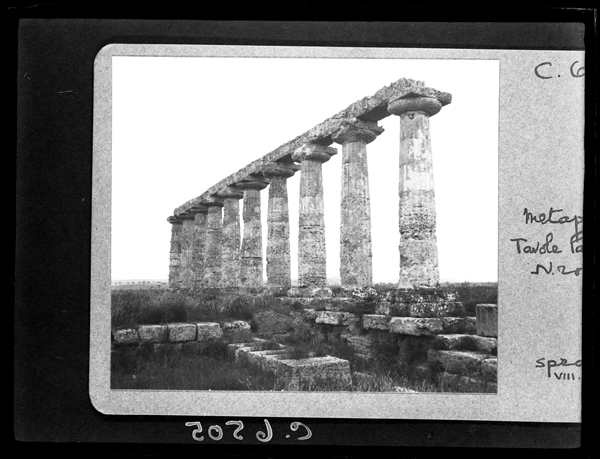

| Sicily & S. Italy | Metapontum*, Selinus** | 74 |

| Istanbul & Asia Minor | Priene* º, Constantinople*, Ephesusº, Troyº | 65 |

| Number of Images recorded in the Negative Register: | 621 | |

| From the first 3 groups of donations: * negatives in BSA SPHS Collection (to make slides); ** missing negatives/slides. From the 4th group of donations: º donated slides |

||

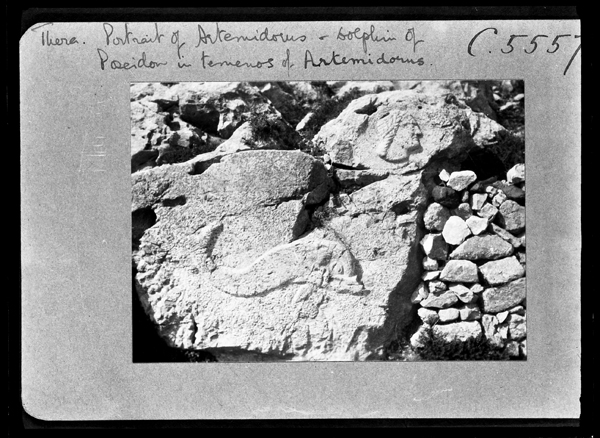

BSA SPHS 01/6411.C5557. Thera (ancient city): Portrait of Artemidorus and Dolphin of Posidon in temenos of Atemidoros

BSA SPHS 01/6409.C5500. Tylissos (Crete): Stone bath and raised water channel leading to cistern, from S

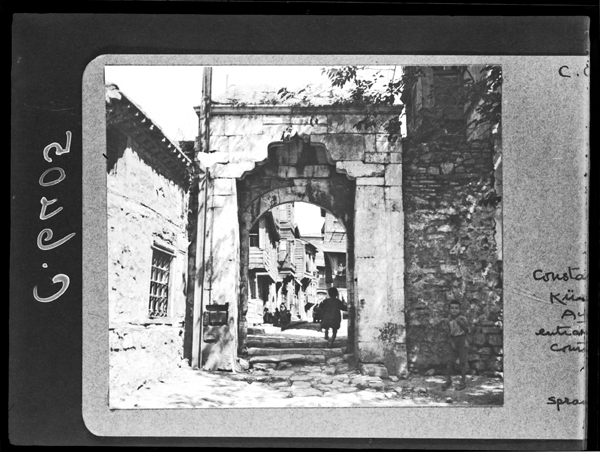

BSA SPHS 01/6569.C6405. Istanbul: Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (Küçük Ayasofia), entrance to courtyard

Spranger tended to concentrate on Classical to Medieval sites with the exception a small number of prehistoric sites – a few locations on Crete, plus Troy on the coast of Asia Minor. What is striking is the absence of the prehistoric icons of the Peloponnese – particularly Mycenae and Tiryns. Although Spranger photographed at Pylos and on the island of Thera, the Palace of Nestor (Pylos) and the prehistoric site of Akrotiri (Thera) had yet to be excavated by the time Spranger visited. The one photograph of Pylos is of the Palaeokastro and all 32 images from Thera are of the remains of the ancient city. Two locations – the island of Ikaria and the area around the River Styx (which has ancient connotations) – were primarily landscape shots without antiquities.

The lantern slides were the working part of the collection, catalogued and offered to members for loan or purchase, primarily used for teaching. Except for the Ionian Islands, all of the general areas are represented in duplicated slides from the first three donations, although not all specific locations – denoting sites the SPHS and its members thought were relevant. The duplicated slides from these earlier donations concentrated around fewer sites which were represented in the registers by larger numbers. All general areas and almost all of the specific locations are represented in slides in the fourth donation. It should also be noted that the slides from the fourth and last donated group represented a larger number of places, each with fewer entries in the register, and in some cases by only one image – Pylos, Eleusis, Gortyn, Samos, Naxos, Praesos, Chios, Eleutherae, and Kephallonia. It appears that the last donation was an attempt on Spranger’s part to present representative images of his travels, not necessarily images of specific relevance to the SPHS community.

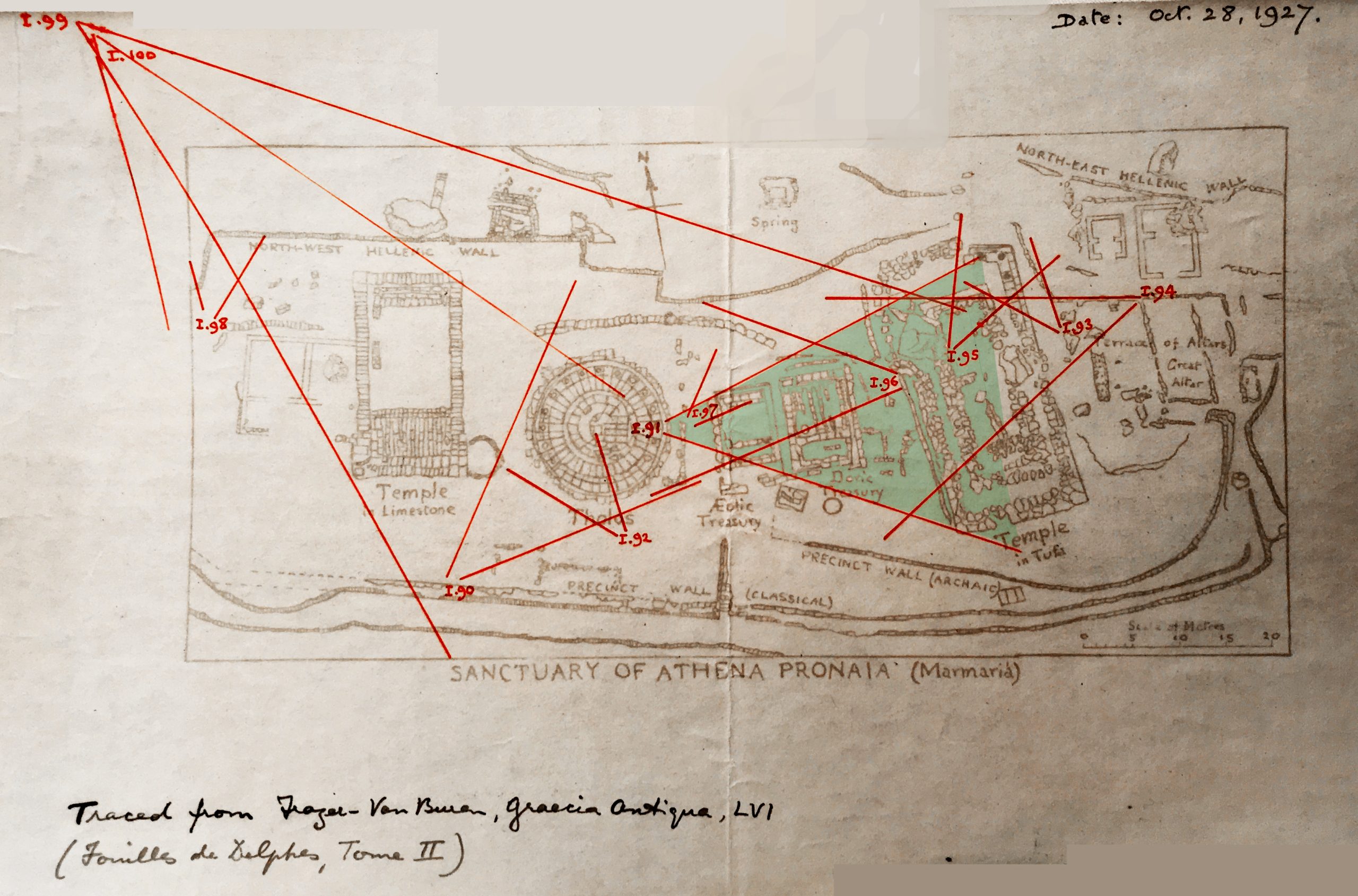

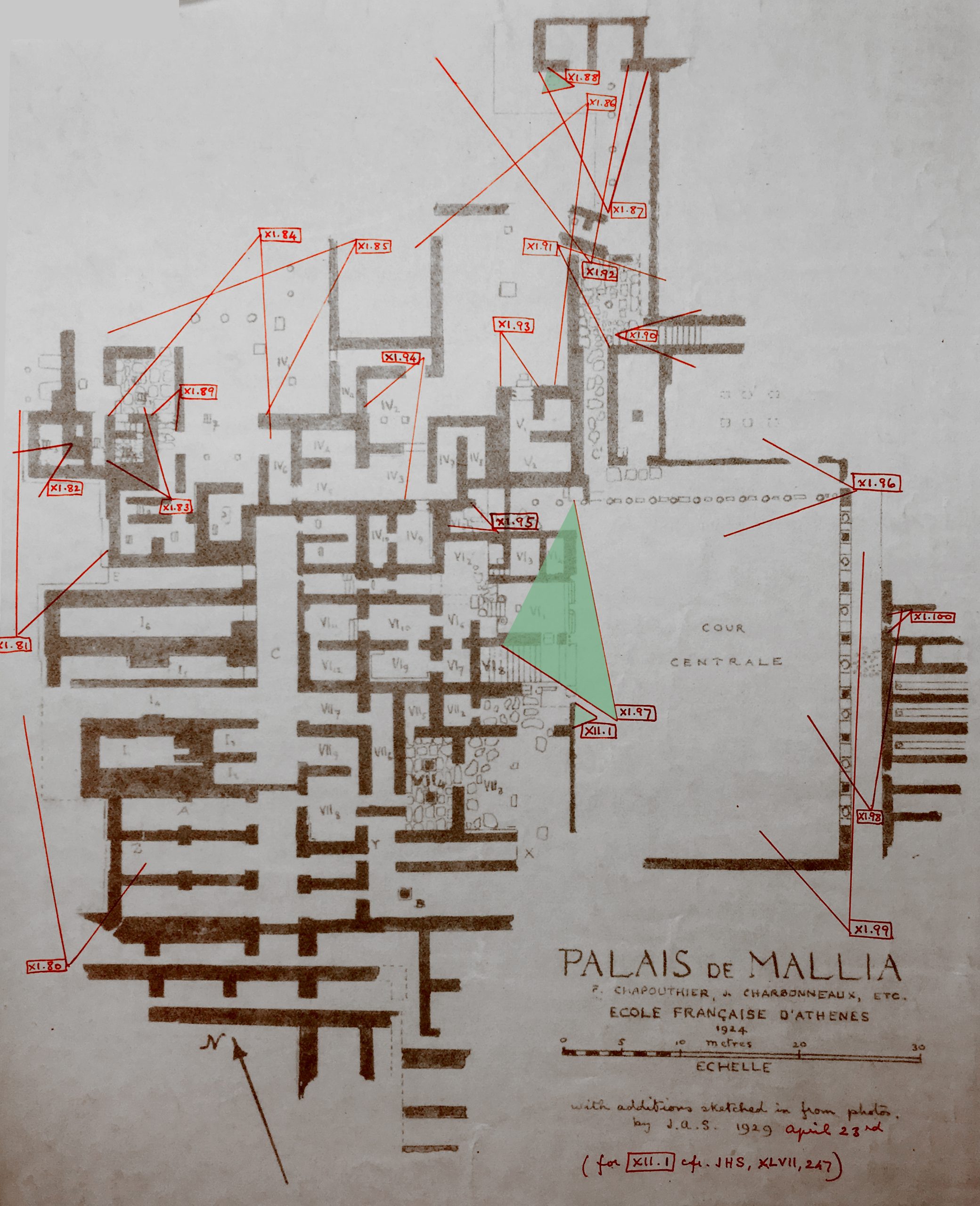

More information on Spranger’s photographs comes from another documentary source: Portfolio of plans giving the position of photographs and slides presented by J.A. Spranger, held by the Hellenic and Roman Library at the Institute of Classical Studies, London. The portfolio, obviously intended by Spranger to accompany his images, contains annotated plans marked with some of Spranger’s photographs and the angles of view as well as precise dates they were photographed. The numbers on the plans refer to his original album and photograph number. It shows the perspectives of the individual photographs – precision work, due to his topographic and engineering training. These plans are similar to the ones he drew for his other archaeological photographs outside Greece. Because of this precision, it is possible that Spranger may have had some knowledge of analogue photogrammetry, particularly given his background in surveying. The concept had been around for a while. In fact, the advantages of using photographs – specifically the methodology of photogrammetry – in map-making were outlined in a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society in 1891. Additionally, the phototheodolite – a combination of camera and theodolite – had also been in use since the latter part of the 19th century to measure orientation of angles, and was used in terrestrial surveying. However, it is unknown if Spranger used such an instrument although the accuracy of his drawn angles suggests he used some form of mapping technique.

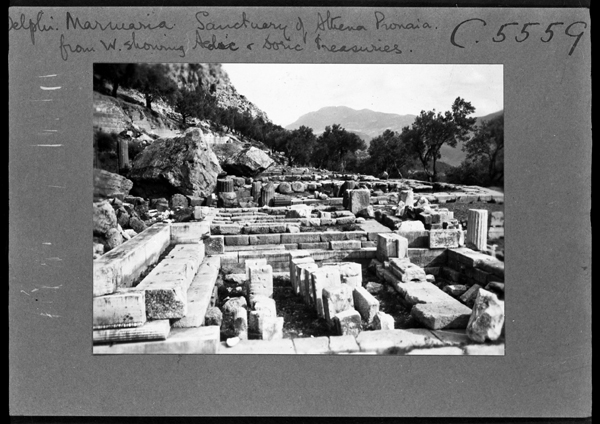

Delphi, Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia (Marmaria), Date 18 Oct. 1927. (Angle shaded to show the image I.91 shown below). Extract from the Portfolio of plans giving the position of photographs and slides presented by J.A. Spranger included with the kind permission of the Hellenic and Roman Library.

BSA SPHS 01/6412.C5559. Delphi: Marmaria Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia from W. showing Aeolic and Doric treasuries (Spranger I.91)

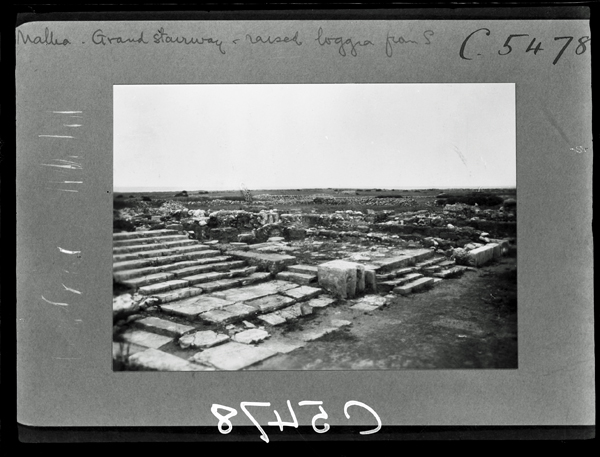

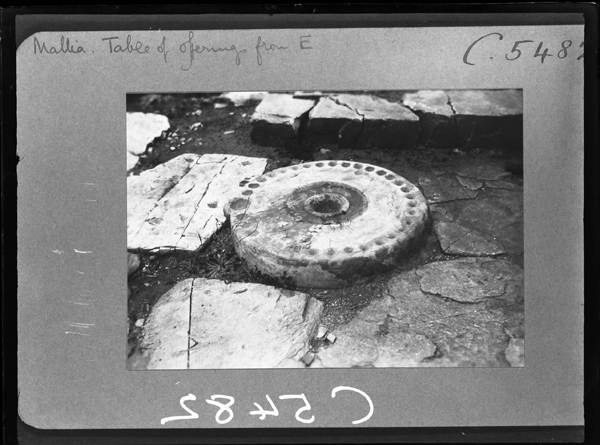

Palais de Malia, Date: 23 April 1929. (Angle shaded to show the images XI.88, XI.97 and XII.1 shown below). Extract from the Portfolio of plans giving the position of photographs and slides presented by J.A. Spranger included with the kind permission of the Hellenic and Roman Library.

These were all holiday photographs taken during the spring or early autumn months from the late 1920s through the 1930s. The large number of landscape shots from Ikaria which have no archaeological significance further confirms holiday snaps. There are also significant gaps in the sites represented to be a comprehensive list of key Greek archaeological sites. Some of the gaps may have been by choice – choosing images that Spranger felt were appropriate for the SPHS. Although, significant gaps may simply be because he did not travel to those locations – such as Epidaurus and Olympia, significant ancient sites in the Peloponnese to miss. It is unlikely that Spranger deliberately chose images of places that were under-represented in the SPHS Photographic Library given his donations of such images depicting Delphi, Limenas (Thasos), Perachora or Ephesus were all well represented in the SPHS Photographic Library. Yet, as an experienced excavation photographer and topographer as well as being a trained mechanical engineer, he took meticulous care to record and plot the views of a number of archaeological sites. By “de-fragmenting” the collection, combining information from a variety sources, we have a better view of the Spranger donation to the SPHS than if we simply told the story from 30 extant negatives from one archive. This story, of course, is only a part of the whole and should also be viewed within the larger picture of Spranger’s archives in Italy which hold original documents.

Deborah Harlan

British School at Athens

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Further Reading

Anastasio, S. & Arbeid, B. 2019. ‘Pioneering archaeological photography in John Alfred Spranger’s 1929-1936 photo reportages’, The Archaeopress Blog, 3 November. Available at: https://archaeopress.wordpress.com/2019/02/27/pioneering-archaeological-photography-in-john-alfred-sprangers-1929-1936-photo-reportages/ (Accessed: 1 June 2019).

Anastasio, S. & B. Arbeid, 2019. Egitto, Iraq ed Etruria nelle fotografe di John Alfred Spranger Viaggi e ricerche archeologiche (1929-1936). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology.

Anastasio, S. & Arbeid, B., 2016. ‘Archaeologia e fotografia negli album di John Alfred Spranger’, in Quaderni Friulani di Archeologia 26: 161-168.

Koutsoumpos, N. 2019. ‘A special individual: J.A. Spranger photographs Greece of the interwar period’, Photographic Encounters 2019 conference held 3-4 May in Chania, Crete. (downloaded from Academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/42287452/A_special_individual_J_A_Spranger_photographs_Greece_of_the_interwar_period)

Thomson, J. 1891. ‘Photography and Exploration’, Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography, 13(11): 669–675.