Creating order: first steps in the archival arrangement of the Mervyn R. Popham Personal Papers

Hello! I’m Kate Wilson, a MARM (Masters of Archives and Records Management) student from the University of Liverpool. In January this year, I came over to the British School at Athens as part of a 2-week placement to learn about description and arrangement within an archive. I had the pleasure of working on the personal collection of Mervyn R. Popham, British archaeologist and Assistant Director of the British School at Athens from 1963-1970. It was an uncatalogued collection which I was let loose with and, in the time available, I aimed to create some order within the chaos under the guidance of the BSA Archivist, Amalia Kakissis.

My primary focus for the first week was to work out the scope of the personal collection and create a loose system that the items and files can be catalogued into. During the second week, I began physically arranging the boxes and organising them into logical groupings whilst building up my finding aid. As I was working in a limited time frame, my priority was ensuring that the next person to work on this collection had a clear foundation to work from.

I did my undergraduate in history and my background is focused on social history, so unfortunately, I have a limited understanding of archaeology. To try and understand the content of the collection as much as possible, I wanted to learn more about Mervyn so I could piece together his papers which all focused one way or another on his love for archaeology. Unfortunately, as he passed away in 2000, most of this information was from his obituary. Born in 1927, orphaned by 1943, he was a passionate student of classics and a founding member of the archaeology society at Exeter School. Following his national service with the Royal Navy from 1946-8, Mervyn read classics at St Andrews and graduated in 1952. Joining the Colonial Service in 1953, he was posted in Cyprus where he photographed objects, visited excavation sites, and conducted research on White Slip pottery which became definitive. Mervyn’s time in Greece was intertwined with the British School at Athens. In the years 1961-3 he was a Senior Student, then followed Hugh Sackett as its Assistant Director from 1963-70. Throughout the 1960s, Popham mastered Late Minoan pottery and wrote extensive articles, monographs, and reviews. Dating the destruction of the Minoan Palace of Knossos would become one of his key research focuses throughout his career, alongside various excavations which merited important finds relating to tombs, metalwork, and burials at Lefkandi and the Unexplored Mansion at Knossos. Following his death in 2000, Mervyn’s collection of personal papers were donated to the British School at Athens by Mervyn’s brother, who over saw his estate, and his close collaborator and friend, Hugh Sackett.

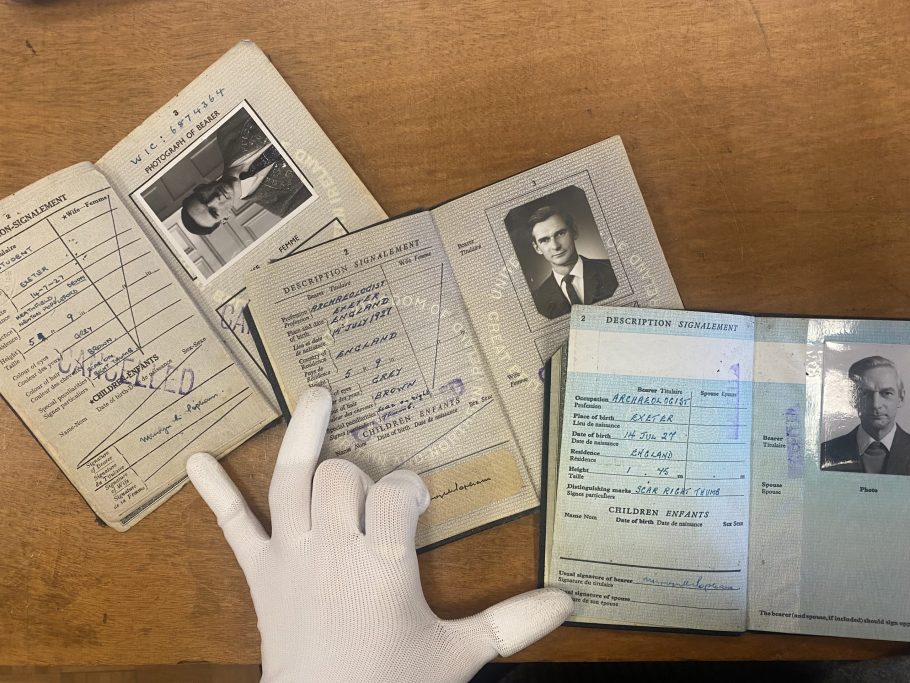

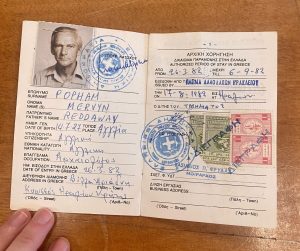

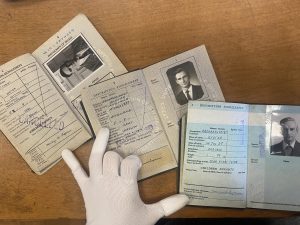

Mervyn’s collection was uncatalogued, but a listing sheet outlining the rough contents of each box was made available in Box 1. This was welcome as I ended up starting my placement a few days late owing to Covid and tonsilitis, so it let me orientate myself with the collection quickly. The first task was to try and work out common threads throughout the collection. The first box consisted of miscellaneous photographs and correspondence. One envelope had scrawled on the front, “Found near photocopier, might be Mervyn’s”. This disorder was visible throughout the collection with various envelopes containing miscellaneous information being found in every box. Interestingly there were a few passports dated from between 1954 to 1989, which not only showed Mervyn’s extensive travels, but also let me see his face for the first time and to understand the passing of time that occurred within all these boxes of personal papers. These documents are slightly unique to the rest of the collection so were placed in POP/2/7/1 containing identification documents.

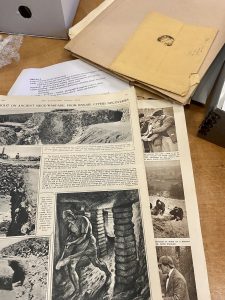

Box 2 focused more on Mervyn’s papers, featuring drafts of articles, conference papers, and correspondence around Mervyn’s publications. Many of the files and envelopes within Box 2 contained various photocopies, articles, and offprints that had been taken from Mervyn’s books. The content within them varied greatly and had little consistency either in date or topic. This made sorting through them a time-consuming process. I separated the contents of this box according to its contents, creating various files on research, miscellaneous papers, conference papers etc. Any material found within envelopes were kept separate to ensure there was no crossover between the intentionally separate material and the rest. As shown in the image, there were files within the boxes that contained various papers that had been found in the folds of Mervyn’s books or on his desk, or as mentioned earlier, near the photocopier. These individual files were placed together into one large file (POP/2/4) titled ‘Materials found in Mervyn Popham’s books’.

It quickly became clear that Mervyn had lots of correspondence, hence the inclusion of POP/1 Correspondence as a series. Within this, I have four sub-series focusing on POP/1/1 Professional Correspondence, POP/1/2 Academic Correspondence, and POP/1/3 Miscellaneous Correspondence. There is also POP/1/4 which was a file put together by Hugh Sackett which has been kept intact. Most of the material was in English, however I had problems translating the odd Greek bit of material so had to turn to the camera on Google Translate in order to work out roughly what the material was talking about. This was one of Mervyn’s bank books that was translated into English!

Box 3 consisted of scientific data, namely chemical and clay analyses with lots of graphs and a few pieces of correspondence, both to and from Melvyn. Most of the contents of this box would become POP/3 Scientific Analysis. It was difficult to catalogue these as I have a limited knowledge of what the documents meant. Most of them contained geographical information and focused on specific areas of Greece. For example, Kea and Knossos were the two most prominently featured throughout the collection. There were also odd bits of correspondence throughout the folders within the box. This correspondence all appeared to be related to the scientific analysis within the box, however I was unable to make any clear connections owing to a lack of contextual knowledge. Therefore, rather than being removed to POP/1, the decision was made to create a separate file within POP/3 to ensure the correspondence remained with the scientific material that it may relate to. There wasn’t enough time to consult the Fitch Lab to help us work out what the material meant, therefore we decided to organise it into files by location. Some files such as Kea (POP/3/1/1) and Phylakopi (POP/3/1/6) already had enclosures within that separated some of the material. These were left in the file in their original state and noted in the finding aid. The series also included two sub-series’, one for correspondence (POP/3/5) and one for miscellaneous papers, graphs, and various chemical analysis (POP/3/2). Also, within POP/3/2 was a file of photographic materials, and a file called ‘Charts of Characteristics’ (POP/3/4). The latter was already in an original paper enclosure and distinguishable as separate from the other analysis and graphs, therefore I maintained this separation through making it a file within the overall series rather than a sub-series.

Whilst I was going through each box and building each file, I typed out my finding aid. This helped me keep track of my sections and allowed me to cover more ground over the short time that I had. I had to go back and forth when changing my reference numbers as the hierarchy of the collection shifted unavoidably, but it was still useful and saved me rushing at the end.

Mervyn was an avid photographer, sharpening his skill whilst in the Royal Navy during his youth. It was no surprise then that his personal collection contained a range of visual materials. Slides, photographs, negatives, rolls of 8mm film, postcards, sketches, and postcards were all present throughout his collection, but were especially present in boxes 4, 5, 6, and 7. After discussing with Amalia, it was inevitable that time would catch up with me which meant I was unable to go through the visual material at an item level. We decided to describe the material at a sub-series level instead which allowed me to make more generalised archival descriptions. After going through the boxes, we decided it would be best catalogued at this time through the medium of the visual material. Hence the division of the series into slides, photographs, film, and miscellaneous which included negatives. Fortunately, the inventory told me how many of each medium there was in the collection, so I didn’t need to go through every box of slides or envelope of negatives manually.

I went into most things on a file level owing to time constraints. As mentioned earlier, my priority was leaving the work accessible for the next person who decided to work on it. Because of this, there were a few things that I went into on an item level either because I had done extra research on them and found interesting information, or because it was the only thing in a file, and I wanted to justify my reasoning for that somewhere for posterity. One example of this was POP/2/1/2/1/1 which was an article titled ‘The Actual State of Research and the Citadel of Mycenae’. It was within a paper enclosure and featured annotations but had little other information. After researching, I managed to find an author and year of publication. I didn’t want this information to go missing so made it an item within my finding aid to pass the knowledge onto the next person working on the collection.

By the end of my last day in the Map Room, I had arranged most of my collection. This is the first time I have ever physically catalogued material, so it was super satisfying to see it all so neatly put away in little paper enclosures and files! I ended up creating 4 series with POP/1, POP/2, and POP/3 all arranged to a file level and POP/4 catalogued to a sub-series level. My finding aid corresponds to the reference codes written on the envelopes for each file, enabling future users to easily find the corresponding information. Though lacking the contextual information that it would have taken to thoroughly catalogue Mervyn’s collection, I’m confident that a general order has been reached that will make navigating the collection a lot easier in future.

I’m very grateful to Amalia for guiding me with the collection and helping me understand archival hierarchies, as well as the archival descriptive standards used by the British School at Athens. It has been motivating to work with this type of material for the first time, especially the letters which paint a rich image of a quiet man who loved Greece. To have spent this time at the British School is an experience I will not forget, and it has been a privilege to work within their superb archive!

Kate Wilson

MARM (Masters of Archives and Records Management), University of Liverpool.