Archiving Women in Archaeology: Helen Thomas Waterhouse

Personal papers of scholars associated with the British School at Athens represent an important part of the Archive. As well as expertise in individuals’ fields, such archives provide a glimpse into their working methods and are testimony to personal histories. When I arrived at the BSA from the MARM (Masters in Archive and Record Management) programme at the University of Liverpool for my cataloguing placement, I had limited knowledge of archaeology and had forgotten what little Greek I’d learned during my undergraduate years. I was, therefore, delighted to be presented with a personal archive of British archaeologist Helen Waterhouse rather than excavation records. There were other factors which appealed. I was intrigued to learn more about women in archaeology, which I presumed to be largely a male domain in the pre-Second World War period. For more practical reasons, I liked that the collection was relatively compact and would thus allow me to create a more detailed catalogue in the short time I had.

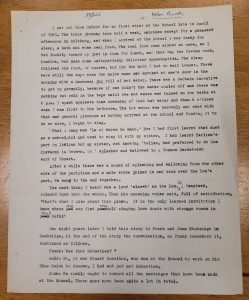

Helen Thomas (centre), with British epigrapher J.M.R. Cormack (left) and American classical scholar Joe Fontenrose(right), enroute to Laurium, ca. 1935

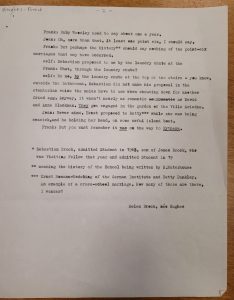

Helen (née Thomas) Waterhouse first arrived at the School in 1935 as a young Cambridge graduate about to embark on a career in archaeology. Although her stay was cut short by the impending war, she did take part in excavations and, though also delayed by the war, completed her first publication. During these early years at the BSA Helen formed important friendships and professional relationships which lasted a lifetime. Much later, in her publication on History of the BSA, commissioned on the occasion of its centenary, Helen often referred to the ‘BSA family’. This sentiment is strongly evidenced in her collection, particularly in her correspondence. I especially enjoyed reading memories of the BSA sent to Helen during her research for the book. Among those was a letter from Helen Hughes-Brock, describing her arrival at the School in 1963 in dire need of a bath, following a strenuous half-week journey:

“I spent my siesta dreaming of that hot water and when 6 o’clock came I was the first to the bathroom. The hot water was heavenly and what with that and the general pleasure at having arrived at the School and finding it to be so nice, I began to sing. What I sang was ‘La ci darem la mano’. I had first learnt that duet as a school girl and used to sing it with my sister. I had learnt Zerlina’s part in Italian but my sister, not knowing any Italian, had preferred to do Don Giovanni in German. So I splashed and wallowed to a Common Market-ish sort of Mozart. After a while there was a sound of splashing and wallowing from the other side of the partition and a male voice joined in and took over the Don’s part. We sang to the end together. The next thing I heard was a loud ‘sloosh’ as the Don, so I imagined, relaxed back into the water. Then his speaking voice said, full of satisfaction ‘That’s what I like about this place. It is the only learned institution I know where one can find one singing love duets with strange women in one’s bath’”

Slightly disappointingly, the singer was not Helen’s husband, Sebastian Brock, whom she also met at the School and who later proposed to her by the laundry chute in the same bathroom.

“BSA Family”

The BSA, it has been said, was a place where romance thrived, generating on average 1.6 marriages per year. Helen Waterhouse too met her husband at the School. The couple first met in the 1930s when Ellis Waterhouse, then the librarian of the British School at Rome, arrived in Athens as part of a voluntary exile following Italy’s conflict with Abyssinia. It is unclear if Helen and Ellis kept in touch after this but their paths might have crossed during the war when they both worked for British Intelligence in Cairo. After the war, Helen returned to the BSA as its librarian and Ellis to his post at Oxford, but they were reunited when they both worked at the University of Manchester in the late 1940s. After their marriage in 1949 Helen left her post as an assistant lecturer in Classics and followed Ellis first to Scotland, and later to Birmingham and Oxford. In Birmingham she became an Honorary Lecturer in Ancient History and Archaeology and she retained her links with the BSA publishing regularly within its annuals.

After organising Helen’s correspondence I gained the impression that archaeology was perhaps more female friendly than I initially assumed. There were numerous letters from other female scholars, some deeply technical, letters from Lisa French – the BSA’s first female director, and multiple letters from the female scholars behind Brown University’s Women in Old World Archaeology to which Helen contributed two biographies. But other material in Helen’s collection painted a different picture. On programmes of lectures and conferences where Helen was either a guest or a speaker she was often the only woman, and always the only one without an academic title and an affiliated university. The BSA had admitted female scholars since its earliest days but they were initially not allowed to reside in the School, receive scholarship or to work on excavations. By Helen’s time such restrictions were no longer in place, but perhaps her story (and her archive) capture other pressures women had to contend with, such as societal norms surrounding marriage and family.

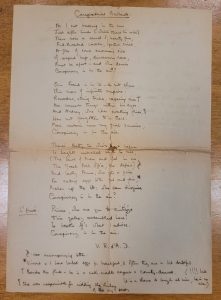

Mothers at work? A site sketch on the same piece of paper as Winnie the Pooh drawing.

After Helen’s death in 1999 her archive was donated to the BSA and arrived in Athens in 2003. There was no catalogue but a shipping index was put together in London to roughly list the contents of each of the 5 boxes. A more detailed index was started in 2020 but like many other projects became a casualty of the pandemic. My task was to organise this collection and create a finding aid adhering to the current International Standard of Archival Description (ISAD – G).

Whilst I liked the personal element of the archive, the process of cataloguing was equally enjoyable, though not without its frustrations. I started by familiarising myself with the collection and its original arrangement. This was a time consuming process, particularly as I found most of the material interesting and had to restrain myself from reading it in detail, but proved useful in both providing contextual knowledge and helping me group material correctly. This was also the first time I considered the frustration of an archivist who has to find the balance between knowing enough to effectively describe the collections but not always having the time to indulge their own interests. I was determined to not disturb the ‘original order’ of the material, but quickly realised that theory and practice do not always go hand in hand.

In Helen’s case the material had already been ‘edited’ by either her family or the secretary of the London and quite possibly both. This was evident, for example, in the labels on individual folders, written in marker pen by the secretary of the London branch. I attempted to keep notes to track everything I moved but this became quite overwhelming and I eventually relaxed into the task. Despite the obvious ‘editing’, there were several instances where the material was likely organised by Helen. Her research notes were arranged alphabetically, grouping together people, places and objects. I chose to maintain this order because it not only provides an interesting insight into her working methods but is also easy enough to search. The majority of Helen’s photographs were in their original envelopes, sometimes including negatives. These were placed in folders with handwritten notes by Helen on content, dates and their location referring to ‘ex desk’, suggesting that perhaps these were arranged during a house move. Organising these was the most time consuming task of my placement, as the negatives had to be placed in individual sleeves.

Once I had physically arranged the material, I started drafting a catalogue proceeding ‘from the general to the specific’ as dictated by ISAD (G). In practice this means separating the material into series, subseries and files. After a discussion with the BSA Archivist, I separated the collection into 4 series: ‘research papers’, ‘visual material’, ‘correspondence’ and ‘conference papers’. Adding descriptions made me look at the material in a different light and sometimes threatened to disturb structures I had previously decided on. What appeared orderly on my desk seemed cluttered when captured on paper. Some adjustments were minor, such as combining several files or changing the name of series to better reflect their content and so ‘research papers’ became ‘research and personal papers’. Other changes were more complex and involved moving material from one series to another. By the end of my placement I had managed to reach file level description for all 4 series but the level of detail differed as some materials were harder to describe than others. I found it especially hard to describe research notes and photographs, lacking the relevant expertise, although I was surprised how quickly I managed to familiarise myself with the material and even gained some unexpected skills, such as being able to recognise Laconia among photographs of other archaeological sites.

The aim of my placement was to put into practice archival description theory and to generate a finding aid that would make the collection more accessible to researchers. It also gave me a better sense of the working life of an archivist, on the one hand frustrated by the shortage of time and resources and, on the other, excited to always learn and to potentially facilitate new and varied research.

Tereza Ward

MARM (Masters of Archives and Records Management), University of Liverpool