Floating colours

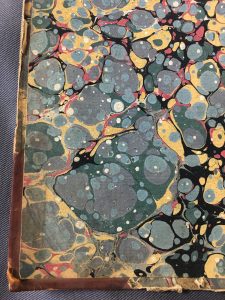

George Finlay’s collection of books spans from the 1790s to 1870s, a period when marbled paper flourished and when many new techniques were introduced by marbling firms keen to outdo each other. We can see the changing fashions during this period hidden inside Finlay’s books.

Marbling came to Europe via the Middle East from the mid-sixteenth century. In the Ottoman Empire, official documents were often written on marbled paper to prevent the alteration of documents – if writing was scraped away and re-written, the break in the background pattern would betray the alteration.

Later, in 18th and 19th century Europe, marbled paper was used to decorate furniture, line drawers and to wrap objects, as well as for books. Many of marbled paper’s uses were temporary and paper was thrown away once it was no longer needed, so marbled endpapers are often the only traces of a much larger industry.

Here are some Finlay favourites.

Finlay’s copy of John Locke’s works. Until the 1820s, books tended to be sold with paper covers, to be bound according to the taste of the purchaser, and so every copy of an edition would have a different binding. Even after publishers began to bind books themselves, owners would often rebind them according to changing fashions or as they became worn. This edition was published in 1794, but as with many of Finlay’s volumes, the binding and those swirling endpapers could date from any time between the publication and the collection’s accession to the BSA in 1889.

Fin R 7.1-9, The Works of John Locke (in 9 volumes), 1794, London: printed for T. Longman, B. Law and Son, BSA Library.

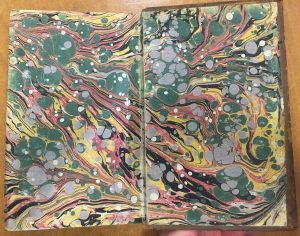

A real eyebender here, decorating George Finlay’s father’s logbook with chemical experiments. French curls remained popular from around 1660 to 1870 and were made by swirling the floating pigments with a stick. They were an easy way to hide imperfections in the base pattern, which may have happened here, since regularity is restored on the back endpaper.

FIN/JF/17, front endpaper. Fern and swirls, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

FIN/JF/17, back endpaper. Stalactites and stalagmites, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

Some less spectacular French curls here, from Coronelli’s account of his journey through Italy .

T 3.13 Coronelli, R. M. A. Arcipelago B. Genova Corsica, etc. Venice n.p, 1688, BSA Library.

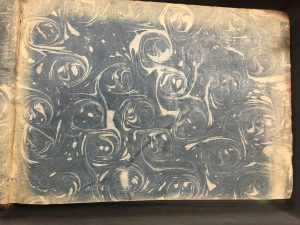

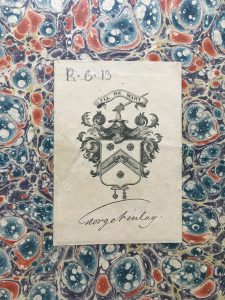

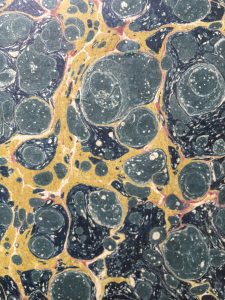

Turkish spot, the first marbling style used in Europe, appeared around the mid-sixteenth century and remained popular until the nineteenth century. Here it decorates Finlay’s commonplace book, which young Finlay stuffed with news clippings, caricatures and sentimental poetry.

FIN/GF/A/33, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

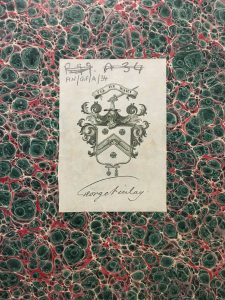

The shell technique, on display in a catalogue of Finlay’s books and a copy of, An Enquiry into the History of Scotland, one of the many books the nostalgic Scot possessed about his homeland. Oil was mixed with the final pigment to be added to the surface, so that the colour of each drop faded towards its edges. A reasonably easy technique.

Fin. R 6.13, An Enquiry into the History of Scotland, John Pinkerton, BSA Library.

FIN/GF/A/34, catalogue of books, 1 January 1848, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

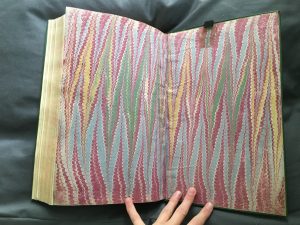

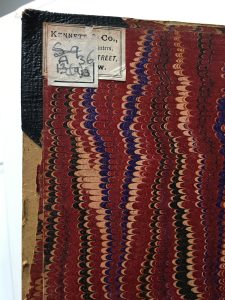

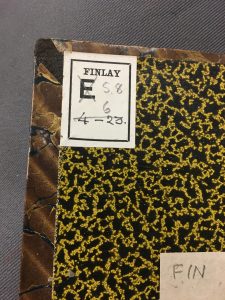

A lovely rich nonpareil, created with a small-toothed comb brushed over the surface of the marbling bath. This style became popular in the 1820s and remained so throughout the nineteenth century. The example here is from another of Finlay’s catalogues of books, this one compiled in 1865.

Catalogue of Books and Maps belonging to George Finlay, Athens, January 1865. FIN/GF/A/36, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

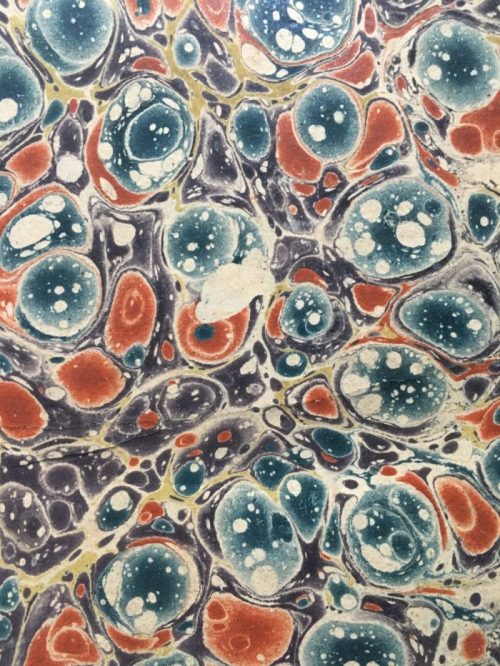

An endpaper with Stormont pattern marbling, from a book of letters. In this technique, which appeared in the nineteenth century, turpentine was used to give the pigment white specks a little like salami.

FIN/GF/B/02, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

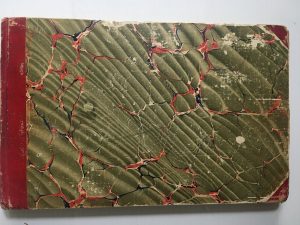

Spanish wave marbling used to cover Finlay’s sketchbook of Greek and Scottish landscapes. The pattern was invented in the mid-nineteenth century and was created by wiggling the paper as it was laid over the floating pigments.

Finlay’s sketch book. FIN/GF/A/02, Finlay Papers, BSA Archive.

Another book with a (this time not so attractive) Spanish wave cover. Judging by the inept binding of some of Finlay’s book covers, they must have been made by a beginner, perhaps even with Finlay’s own hands. Here we can see the corner of the cloth binding poking through through the too-small paper covers.

S 8.6, Various publications bound together by Finlay under the spine title, Roman History Tracts, BSA Library.

I’d be interested to know how marbling papers were chosen for different works, or if there was a link between an endpaper’s style and the content of the book it decorated. Would a nonpareil be more likely to be associated with a serious or academic work, or a Spanish wave for more fanciful writing?

Next time you pick up a Victorian volume, crack open the cover and take a look for yourself.

Felicity Crowe

The 1821 Archive Project Assistant

British School at Athens

For more information on this BSA research project and to see more 1821 Archive Stories, visit the dedicated webpage, Unpublished Archives of British Philhellenism.