Map Annotations

While sorting through and cataloguing the rare map collection at the BSA, I noticed that a number of the maps had handwritten notations and drawn lines on them. These annotations highlight specific points of interest, delineate routes or paths between one place and another, and, in the case of inscriptions, provide information on owners or donors. Collectively, they provide additional information to that originally intended by the producers of the map. Older annotations made at the time a map was relatively new or thought to be in common use often add historic value even as they mar the map’s original pristine condition. This is particularly true if the author of the marks was a well-known figure. Yet, others in the past treated maps as tools of the trade, often as base maps to add illustrations for their own purposes, regardless of the maps’ age or value. However, if we were to do this today with an historic or rare map, it would be, of course, an act of vandalism.

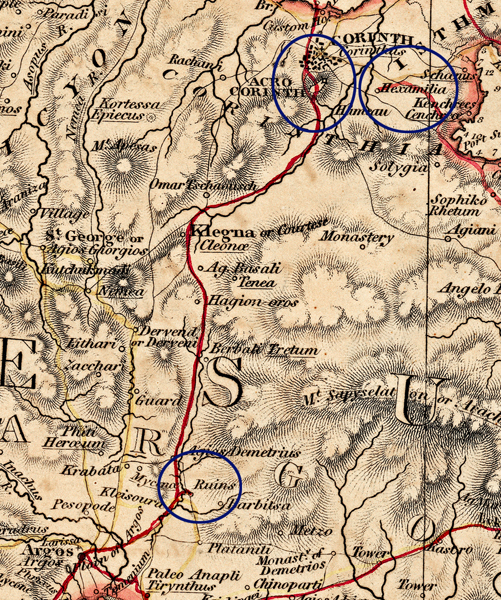

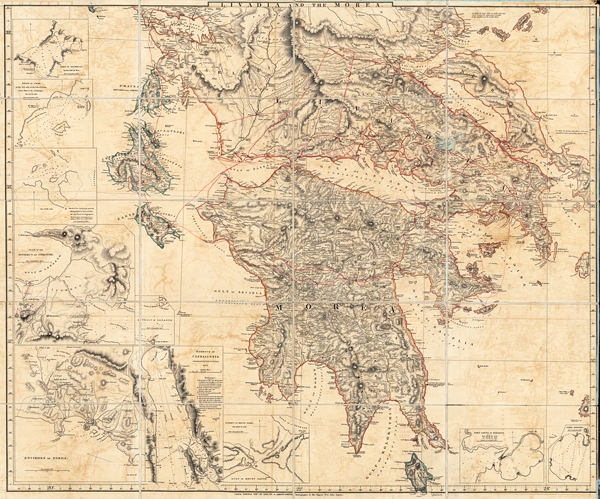

Many of the annotations on old maps are clues to how the maps were used as visual tools by those who handled them in the past. I already made reference to one of George Finlay’s maps in a previous Library Story (Exploring Conscious and Unconscious Decisions in the BSA Map Collection) on the lines drawn on what was then a standard commercial map (dating to 1826), probably by Finlay himself, to mark his routes around Central Greece, the Peloponnese and Attica. This, of course, makes the map unique and demonstrates the vast distances travelled by the 19th-century historian of the Greek Revolution. If you look closely, it also shows where Finlay travelled to observe places of archaeological interest. In the detailed example below, you can see Finlay’s route between Argos and Corinth where he stops off to take a slight detour to see the “ruins” near the village of Mycenae, then closer to Corinth, he completely goes around the summit of “Acro Corinth”. Another route nearby terminates at “Hexamilia”, the location of a preserved section of the Hexamilion, the ancient fortification wall across the isthmus that defended the entrance to the Peloponnese by land.

Rare Map Collection D 3.1: Greece and Adjacent Countries with Modern and Antient Names by A. Arrowsmith: Livadia and the Morea

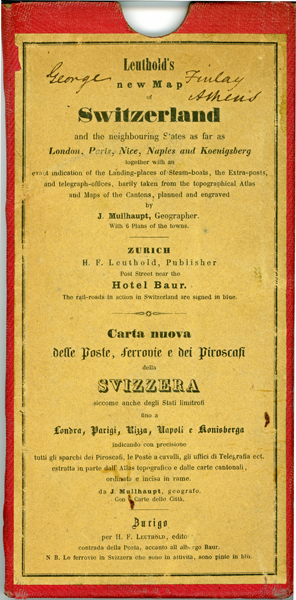

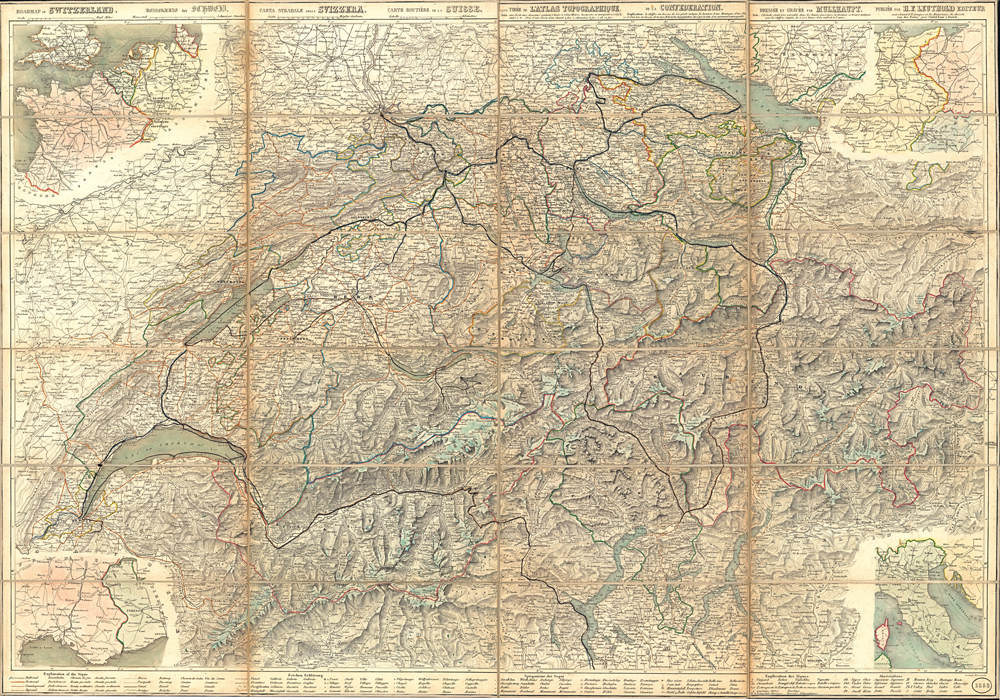

It seems that George Finlay, a great traveller, was prone to draw lines on maps. Below is a standard tourist map of Switzerland definitely owned by Finlay as he signed his name on the map case. The map dates to 1858 and was published by H.F. Leuthold of Zurich. There is little doubt that Finlay purchased this for his planned 1868 visit to Switzerland to observe the Swiss Lake Village excavations. By the mid-19th century, antiquarians were acknowledging the unique preservation of material in these Neolithic Pfahlbauten or pile dwellings that provided fodder for the nascent concept of prehistory. Finlay, now late in his life, was also engaged in this research aiming to understand similar material – primarily stone tools – from Greece and their implications for a prehistoric past before texts in that country. During his stay in Switzerland, Finlay travelled extensively as shown by the routes drawn on the map seen below.

A year after his Swiss visit, Finlay privately published (in Greek) a pamphlet on Observations on Prehistoric Archaeology in Switzerland and Greece (Παρατηρήσεις επι της εν Ελβετία και Ελλάδα προιστορικής αρχαιολογίας). His copy of the pamphlet is in the BSA Library and his English manuscript is in the BSA Archive. Like all of his contemporaries, he also purchased objects. Some of these objects came to the BSA in 1899 when his nephew presented Finlay’s collection of books, maps, papers and objects to the BSA. The item below is an interesting example of how Finlay was attempting to understand how the artefacts were used in the past by combining an antler haft found at the site of Robenhausen near the village of Wetzikon (slightly southeast of Zurich and on one of the lines Finlay drew on the map) with a stone tool insert from the site of Wangen (on Lake Constance, also along one of the map’s lines).

MUS.M135. Finlay Collection. Antler Haft and Stone Tool from the Swiss Lake Villages and detail of Finlay’s map showing the findspots of the antler and stone tool

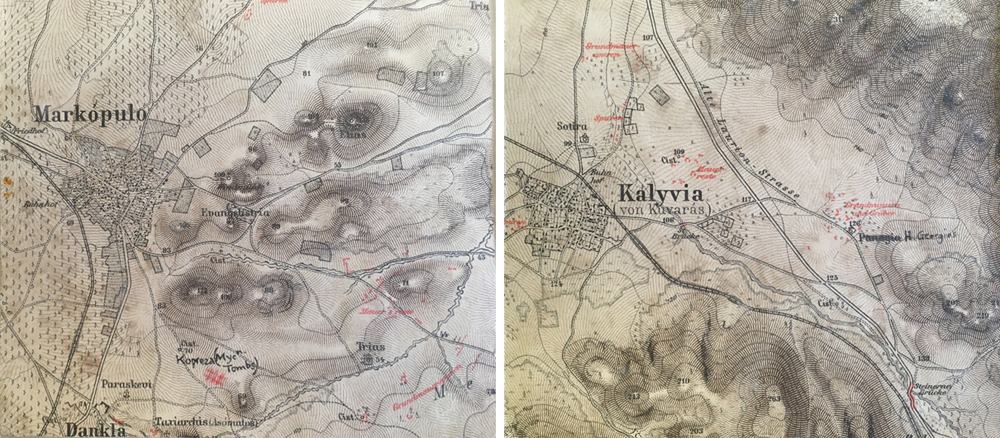

The map series Karten von Attika was a joint effort of the cartographer, Johann Kaupert, and archaeologist, Ernst Curtius, who produced a printed map annotated with archaeological remains around Attica between 1862 and 1897. The map sheets are basically topographic, but contain contemporary structures such as settlements, road, ports, quarries etc. Archaeological remains known at the time are printed in red. On one map sheet for the Markopoulo (Μαρκόπουλο) area of Mesogaias in the BSA Map collection an anonymous archaeologist added two handwritten annotations – one to add the Mycenaean tombs at Kopreza immediately southeast of Markopoulo and a correction to a church name east of the town of Kalyvia [Thorikou]. The marks were possibly made in the years following WWII when numerous BSA scholars were exploring the hinterland of Attica, treating these maps as working tools of the archaeologist’s trade rather than rare maps. It should, however, be noted that at this time contemporary maps at this detailed scale were not available.

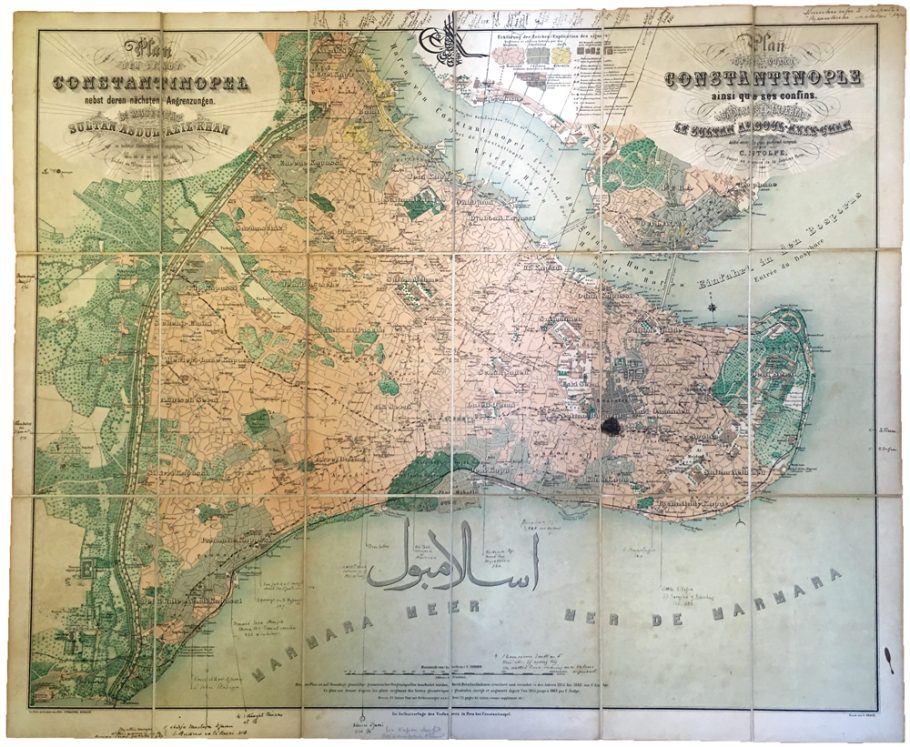

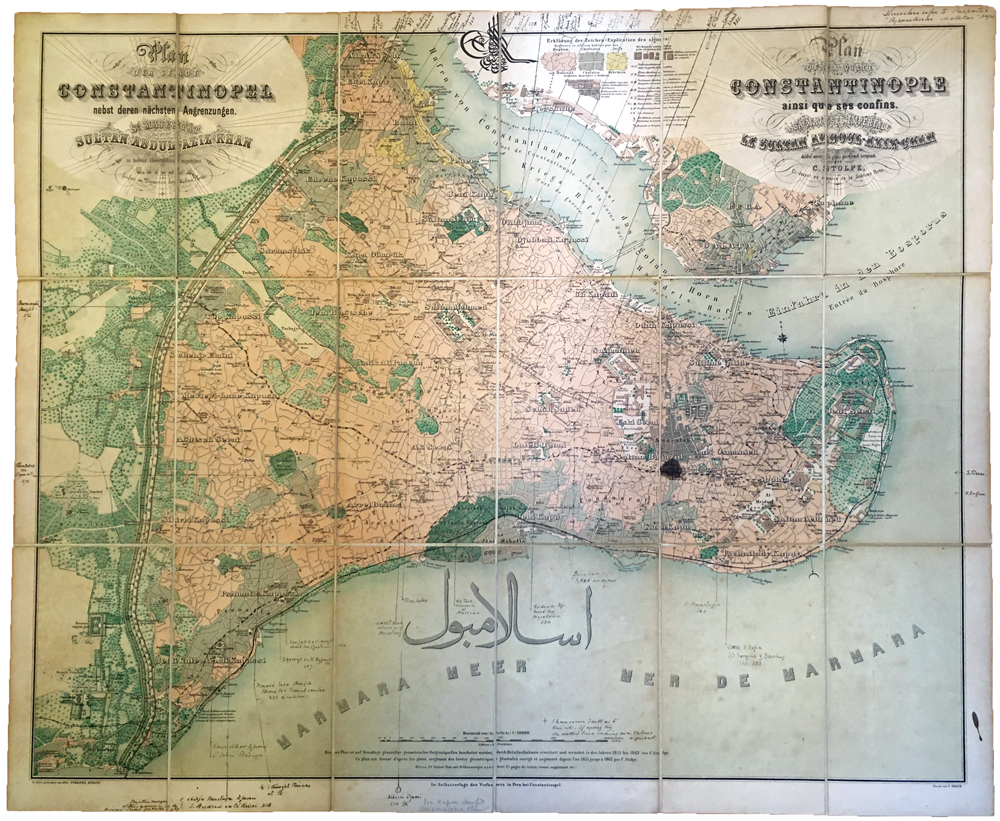

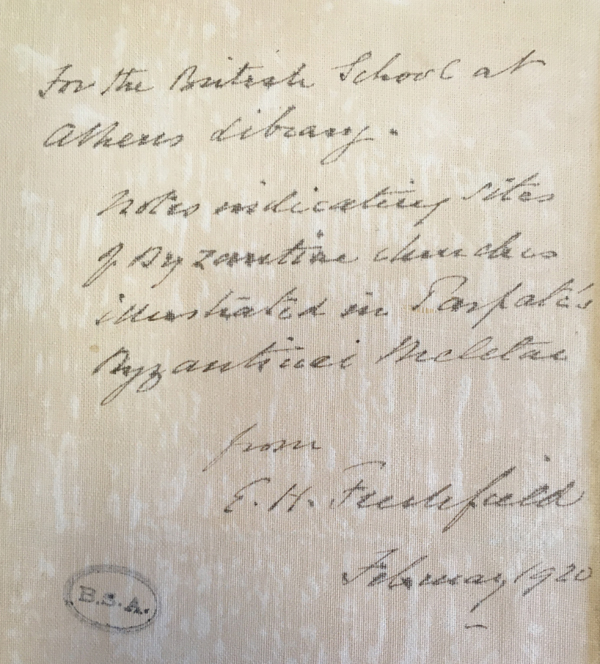

Prussian surveyor Carl Stolpe was noted for his coloured maps of Constantinople produced in the 1860s. Stolpe’s maps were often created for European tourists to the city with explanatory text in French and German. The map drawn by Stolpe illustrated below was published by Julius Straube, the German publisher, for the Austrian Geographical Institute in 1863. It, however, only serves as a base map. A handwritten note on the reverse of the map, signed by the donor, the Byzantinist Edwin Hanson Freshfield, is dated February 1920 – over half a century after the production of the map. The note indicates that Freshfield marked the sites of Byzantine churches as illustrated in Paspates’ Byzantinai Meletai or Churches of Constantinople (Αλέξανδρος Πασπάτης, 1877. Βυζαντιναί μελέται Τοπογραφικαί και ιστορικαί), and presented this map to the Library of the British School at Athens. The church names and page numbers in Paspates’ publication are written in the map’s margin with lines indicating their position.

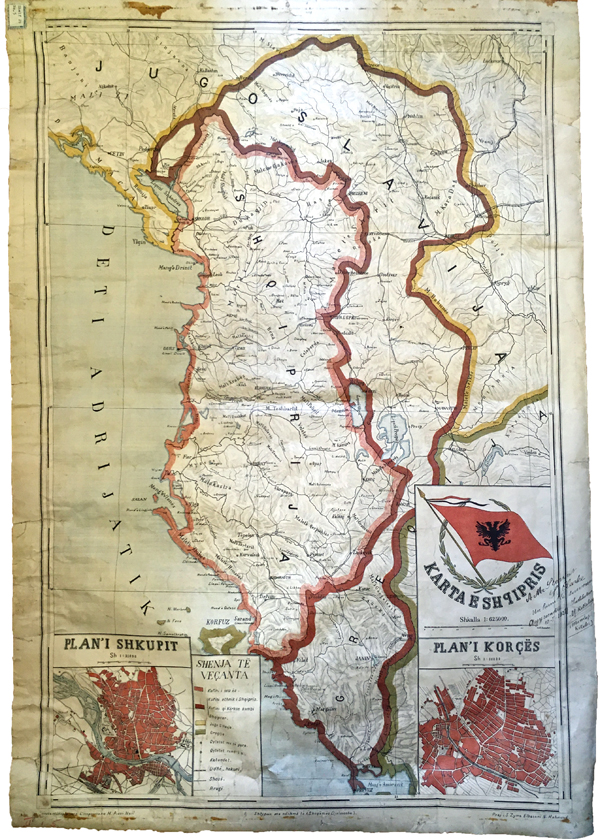

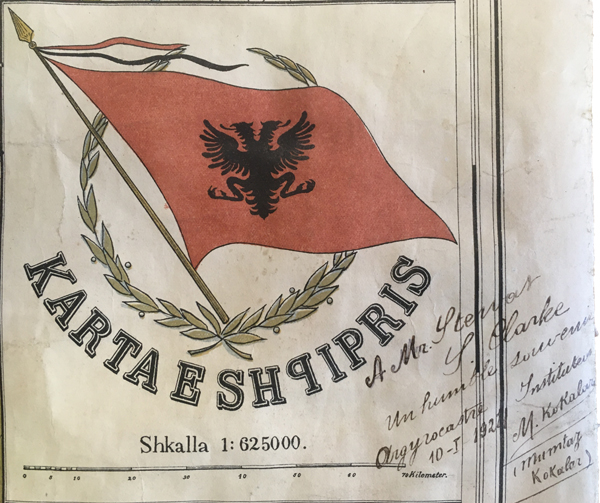

Another map with an inscription is the Karta e Shqipris or map of the Principality of Albania (Principata e Shqipërisë ), a short lived monarchy (1914-1925) established not long after Albania became independent from the Ottoman Empire. The inscription is a type called a gift inscription. It was presented to Mr Stewart S. Clarke from M. Kokalari of Gjirokastër (Greek Αργυρόκαστρο / Argyrókastro) dated 10 January 1922. M. Kokalari, otherwise known as Mumtaz Kokalar, was one of the older brothers of Musine Kokalari, the first Albanian woman who became a published author who was also the founder of the Social-Democratic Party in 1943. The family were progressive intellectuals and when the communists came into power post WWII, Mumtaz and his brother Vejsim were executed and a few years later Musine was arrested and imprisoned for sixteen years. In the academic year for 1922-1923, Stewart Clarke was listed as a student at the BSA who was studying the historical topography of Epirus and Albania, and it is likely he met Mumtaz Kokalari and possibly other members of his family at that time. Tragically, Stewart drowned off the coast of Salamis in 1924. The Clarke Memorial Fund was established to enable an undergraduate from either Balliol or Exeter College Oxford to visit Greece during the Easter vacation and taking up temporary studentships at the BSA. The BSA holds Clarke’s archive of personal papers and notebooks that document his surveys in Northern Epirus and Southern Albania. This map likely came to the BSA with his archive.

Do these annotations add historic value? It seems there is a fine line between annotations of merit and those that depreciate. Finlay’s maps certainly add value, possibly because it was George Finlay, a notable figure, who marked common commercial maps at the time. They have become unique documents illustrating aspects of Finlay’s life. This could also be said for the map gifted to Stewart Clarke, a poignant reminder of a brief and turbulent time and the dramatis personae in Albanian history. However, it is unclear if the anonymous archaeologist or even E.H. Freshfield defaced the maps or if they simply used them unwittingly to illustrate scholarly information. Luckily, we are not faced with this dilemma as we now have digital alternatives which we can quite happily annotate without damaging the originals.

Deborah Harlan

British School at Athens

The BSA Map Collection is catalogued on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Library Stories.