1936: Exhibition Season & The British School at Athens

There comes a time in the life of an institution when it feels the need to reflect on its past glories and fêted in the form of a series of special events such as public lectures, conversazione, and ceremonial banquets. In 1936, the British School at Athens (BSA) turned 50, a landmark to celebrate. No written histories of the BSA were commissioned at this time, as is common for such landmarks. George Macmillan had published a short history of the BSA in the 1910/1911 Annual of the British School at Athens, detailing its first 25 formative years and an elaborate anniversary dinner was held in London to mark that occasion. The BSA’s 50th anniversary, however, coincided with the recent publication of the last volume of Arthur Evans’ Palace of Minos. Although not originally a BSA project, Evans had handed his interests in Knossos to the BSA in 1926 making it logical to create a special event to combine these two milestones.

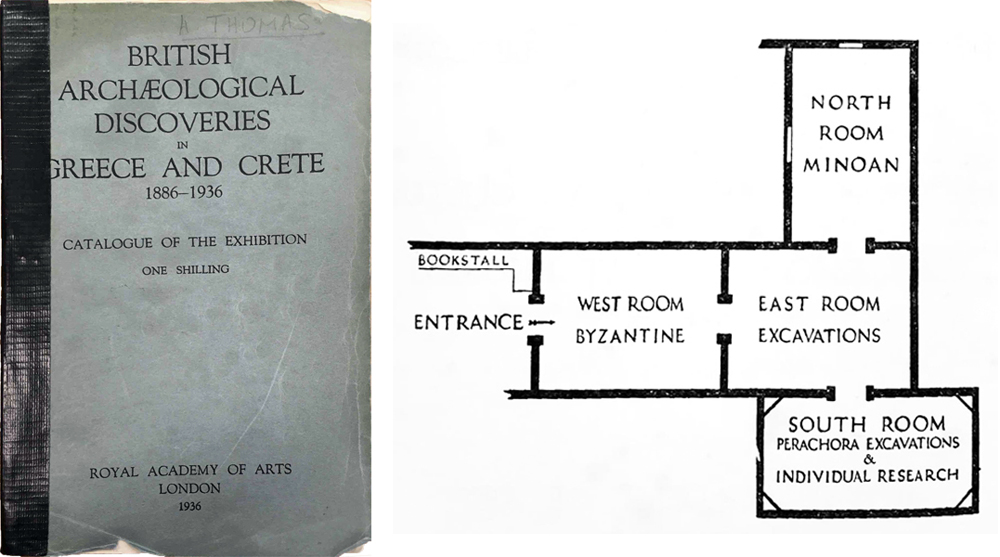

A committee was set up to curate a grand exhibition on the British Archaeological discoveries in Greece and Crete 1886 to 1936. Among those on the committee were Arthur Evans, John Myres (Chairman of the BSA), Robert Weir Schultz (Byzantine Research & Publication Fund), Vincent York (Treasurer of the BSA), and E.J. Forsdyke (Director of the British Museum). Archaeological exhibitions in London were a common feature of the social season from the last decades of 19th century. According to Amara Thornton, they were a way of ‘exploring the reception and sponsorship of archaeological work overseas and its promotion to a fascinated, well connected and moneyed public’. The venue the exhibition committee chose was the premier one in London: the Royal Academy set within the Burlington House complex.

Organising the exhibition involved more than the major undertaking of selecting objects for display and gallery arrangement, but also the production of an exhibition catalogue, and the set-up of a bookstall selling the Annual of the British School at Athens as well as books related to work by BSA scholars. A suitable period that fell within the London social season needed to be set – October 14th to November 14th. A series of illustrated lectures was organised for every Wednesday and Friday during the exhibition at 3:00 p.m. followed by gallery tours of related areas. The inaugural lecture on the 16th of October was given by Arthur Evans on The Minoan World, followed by two weekly lectures by some members of the organising committee (Bernard Ashmole, D. Talbot Rice, and A.J.B. Wace) and other BSA notables (R.M. Dawkins, Theodore Fyfe, J. Droop, and Winifred Lamb). Costs were set for admission, catalogue, and lectures, all one shilling each. The price of 5 shillings for a season ticket, inclusive of lectures, was a bargain. The opening ceremony was inaugurated by His Royal Highness the Duke of Kent on the evening of the 13th of October with luminaries from the Greek diplomatic and British academic spheres present. All was set for a glittering month of exhibition fever.

Left: Cover of Exhibition Catalogue (BSA Archive copy); Right: Plan of the Exhibition spaces from the Exhibition Catalogue.

The exhibition extended over four connected gallery rooms at the Royal Academy. Exhibits consisted of many display boards as well as a replicas and few original antiquities (primarily from private collections or from museums in Britain). Many of the photographs mounted on the display boards came from the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS) photographic collection, originally donated to the SPHS by the scholars whose work was being displayed. There were four themes running through the collection – Minoan, BSA Excavations, Individual Research, and Byzantine. The catalogue was written for the general public, not an academic audience, somewhat pedagogic but often employing poetic descriptions and hyperbole. It, however, reflects public perception – or what the authors of the catalogue thought would appeal to the public on the subject of Greek and Cretan archaeology.

Below are the various rooms and sections as laid out in the Exhibition Catalogue. They are presented, with some explanatory text, in an attempt to re-create the an experience of a tour of the galleries complete with captions from the catalogue. The photographs of the actual gallery spaces as well as those on various boards are now in the BSA SPHS Image Collection and the boards form part of the 1936 Exhibition Collection in the BSA Archive. The two plaster replicas of Minoan objects are held in BSA collections.

I. Minoan

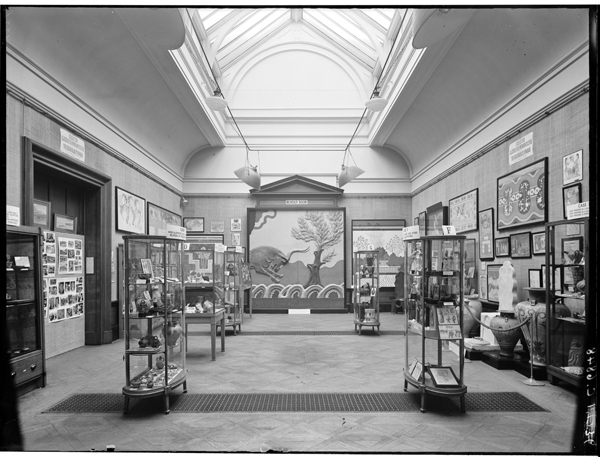

The first half of the exhibition highlighted Evans’ excavations at Knossos and related areas on Crete. One entire gallery space was devoted to the Minoan World which is shown in the photograph below: ‘View of the Minoan Room’. The catalogue record for the photograph in the BSA’s Digital Collections, BSA SPHS 01/6839.C6848, allows for zooming in to see the details of the cases. There were a number of free-standing glass cabinets containing a mixture of original artefacts and replicas. Items were also mounted on the walls including fresco reconstructions, photographs and drawings. The introduction to this section in the Exhibition Catalogue was written by Evans, told in the first person.

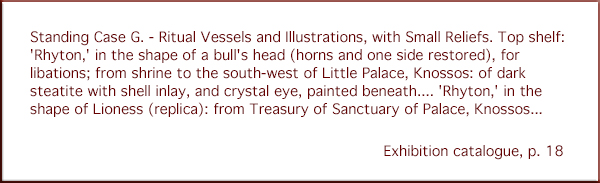

In the standing cases there are many objects, some of which are replicas. It is well-known that Arthur Evans had many replicas made of objects he discovered. Replicas at this time (pre-WWII) were considered to be useful teaching tools and were distributed to various scholars and institutions, very much in the same tradition as cast galleries of sculpture created in the 18th and 19th centuries. To Evans, they also aligned with his notions of ‘reconstitution’ of his Minoan culture. The BSA has the replica of the Knossos lioness rhyton which appeared in the 1936 exhibition – which you can just see behind the bull’s head rhyton in the far right case (Case G) in the main gallery space. Similarly, the BSA’s Knossos Research Centre has a plaster replica of the bull’s head rhyton (also seen in the glass case), although it is unknown if this particular one appeared in the exhibition.

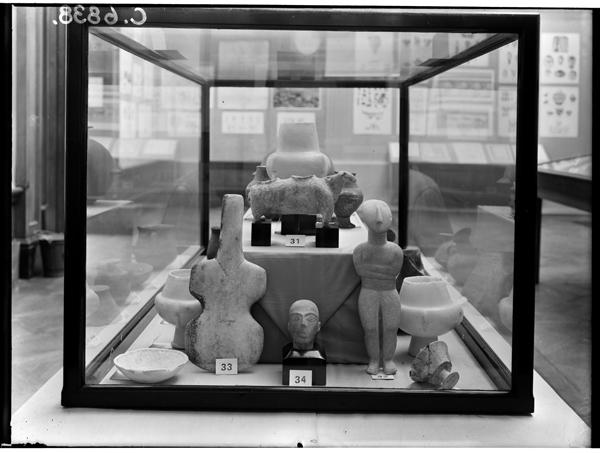

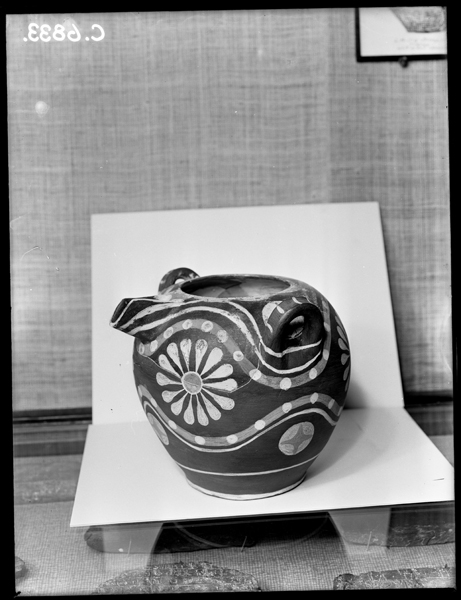

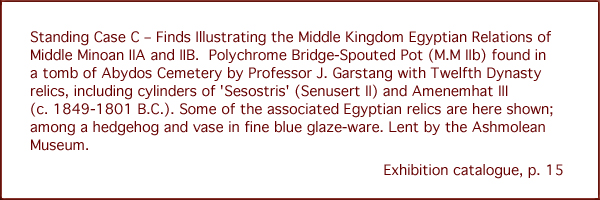

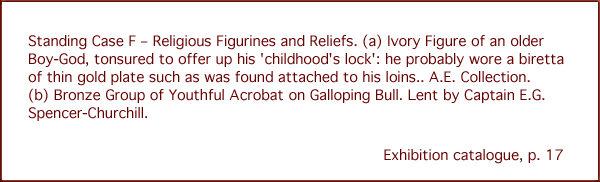

Other objects included a Minoan bridge-spouted jar found in Egypt, demonstrating connections with Egypt. This pot is visible in the gallery space in the near left standing case. On the other side, in the near right standing case, are small sculpted pieces, described as Religious Figurines. Both of the figurines shown in the image below are now in the Ashmolean museum: an ivory figure from the Arthur Evans collection and the other, a ‘bull leaper’ lent by Captain Spencer-Churchill for the exhibition, but later purchased by the museum.

BSA SPHS 01/6824.C6833. Middle Minoan IIb bridge spouted vase from a tomb in the Abydos Cemetery, Egypt

BSA SPHS 01/6827.C6836. Minoan ivory figurine of a tonsured boy-god and a bronze bull with acrobat figurine

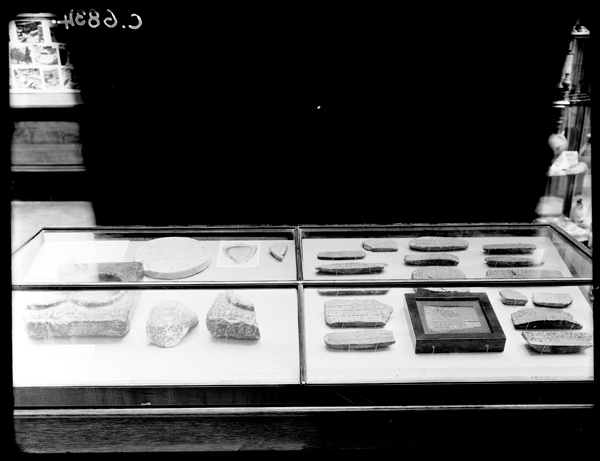

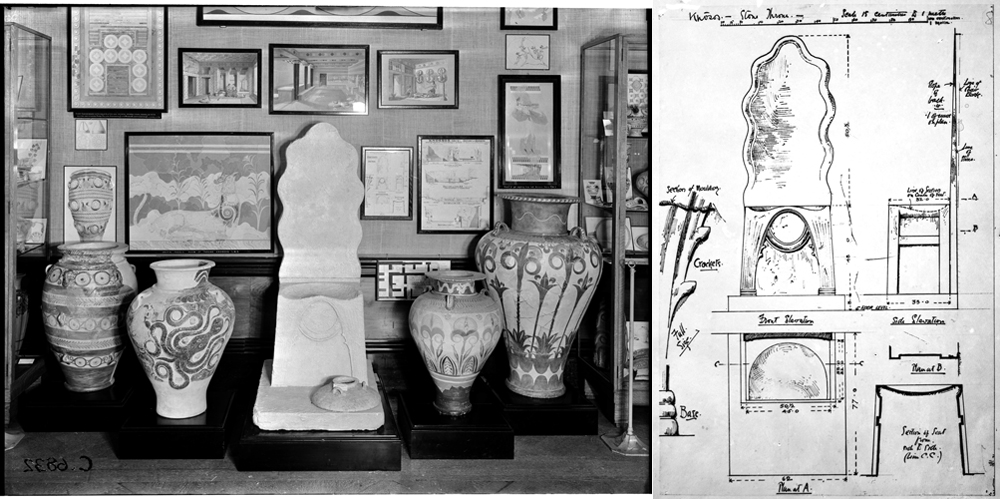

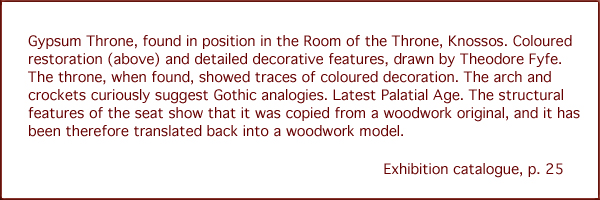

On the right-hand wall of the gallery space as you enter was a display that highlighted the throne from the throne room at the palace of Knossos, one of the first areas Evans excavated. At the base of the throne is a flat alabastron and on either side are large painted Amphoras – one with an octopus and the other with conventionalised papyrus (from the Little Palace). On the wall above the throne are drawings of restorations, several restored frescos and artefacts. Immediately to the right of the throne was a diagram showing the construction of the throne by Evans’ architect, Theodore Fyfe. On another wall is a desk case which showed objects with linear writing, something of particular interest to Evans, although his own aspirations to decipherment were unfulfilled.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/6823.C6832. View in the gallery space of a replica of the Knossos throne, Palace style vases and mounted displays. Right: BSA SPHS 01/2037.5247. Plan, section and elevation of the throne (original drawing done by D.T. Fyfe.

II. BSA Excavations

The principal BSA excavations were listed in the exhibition catalogue, beginning in the late 19th century: Cyprus, Megalopolis, and Melos (see Archive Stories: Digging I and Digging II). Followed by various early Cretan Excavations (see Archive Story: Digging Crete) as well as the major excavations at Sparta (see Archive Stories: Sparta Begins and Return to Sparta), Mycenae and Perachora. Other excavations included work by students of the BSA included Alan Wace and Maurice Thompson’s excavations in Thessaly, W.A. Heurtley’s excavations in Macedonia and the Ionian Islands, Winifred Lamb’s excavations on Lesbos, John Pendlebury’s sites in Lasithi, and various excavations in the Knossos Valley. The Exhibition took up one and a half gallery spaces, described in 40 pages of the catalogue, providing views of sites, but significantly, a taster for the extensive amount of material the excavations generated.

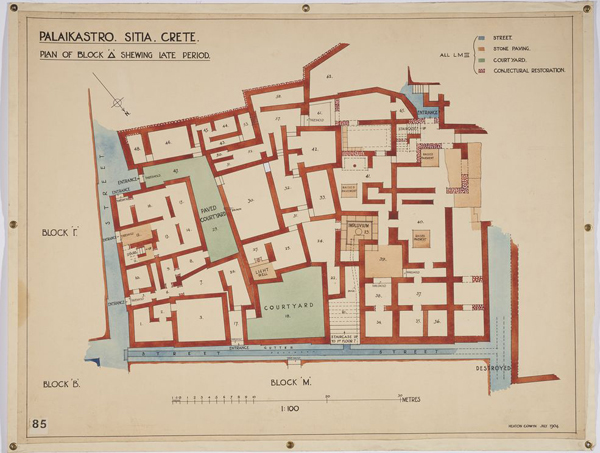

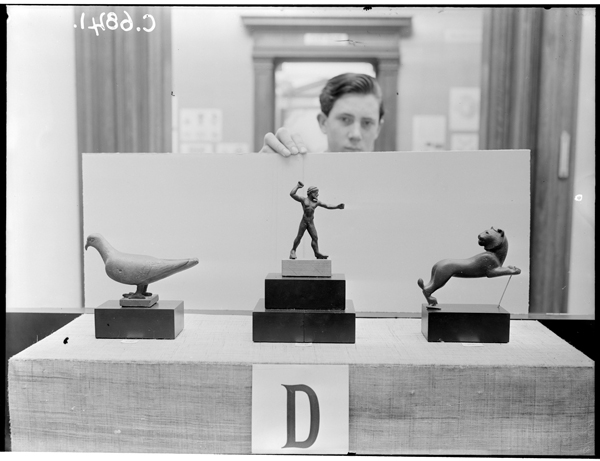

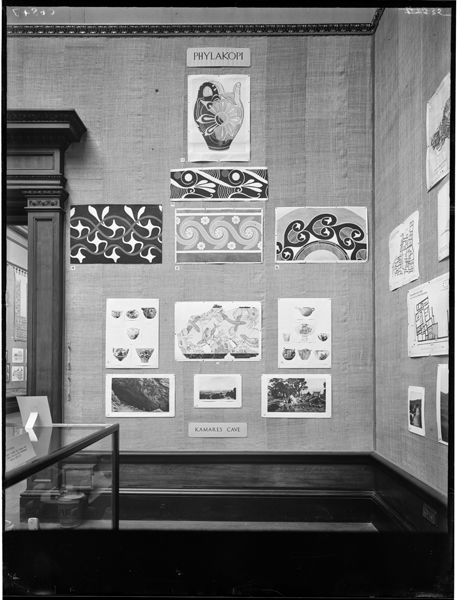

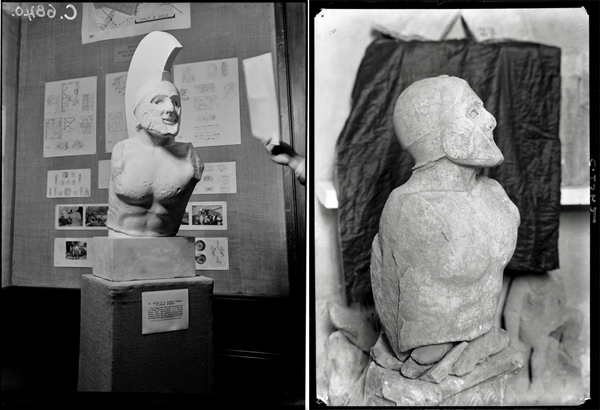

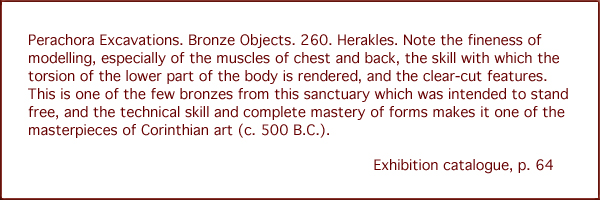

Below are images from the gallery spaces and various SPHS images that made up the displays. One wall in the East Room contained photographs and drawings from Phylakopi and the Kamares cave. A floor case highlighted some early Cycladic material relevant to the excavations at Phylakopi on Melos. Exhibition boards show the plan of one of the insulae of the site of Roussolakos at Palaikastro and Pottery from Mycenae. And, the plaster replica of the Spartan statue, the so-called ‘Leonidas’, was free-standing on a plinth in the gallery. In the South Room, a case showed bronze objects from Humfry Payne’s excavations at Perachora.

BSA SPHS 01/6838.C6847. The wall in the gallery space showing images of material and scenes from the excavations at Phylakopi, Melos (No. 13-18) and Kamares Cave, Crete (No. 71-75).

Left: BSA SPHS 01/6831.C6840. Plaster cast of the Spartan warrior known as ‘Leonidas’ in the gallery space . Right: BSA SPHS 01/7440.C2562. Sparta: head and torso of a 5th century warrior from the Acropolis, in profile (photographed during excavation)

III. Individual Research

The Individual Research category represented a broad spectrum of topics. In effect, it reflects the founding principles of the BSA beyond archaeological research. In the opening chapter of the catalogue, it describes the BSA as founded to ‘provide students of the literature, art, architecture, archaeology, and history of Greece of all periods from the earliest times to Byzantine and modern days’. This section was broken down into sub-divisions: Travels and Studies of Sites and Monuments, Special Studies (Pottery, Sculpture and Reconstructions), The British School at Athens, and Studies in Modern Greek Life. The majority of the displays in this category consisted of boards with photographs.

Travels and Studies of Sites and Monuments

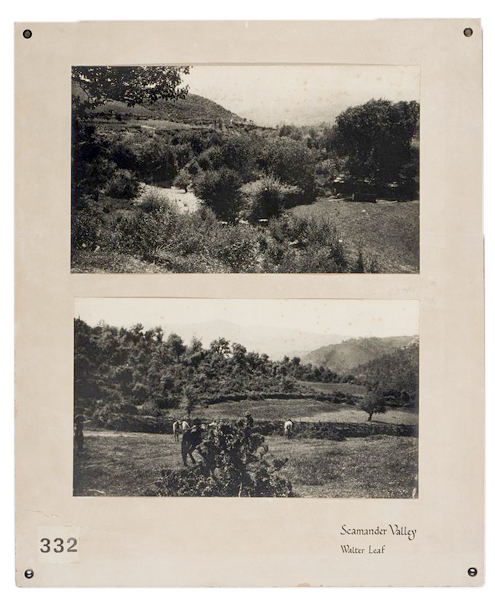

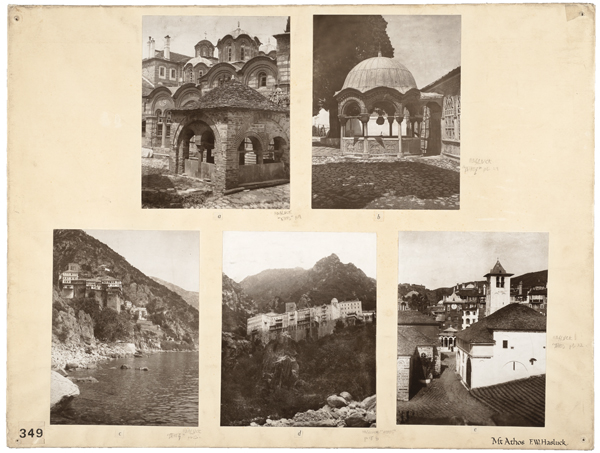

A great number of activities on a broad number of subjects are displayed in this particular sub-category: the discovery of the Villa Dionysos at Knossos by R.W. Hutchinson, a survey of ancient Greek mines by O. Davies, Ionic columns drawn by R. Weir Schultz, D.G. Hogarth’s numerous travels in Anatolia, F.W. Hasluck’s travels and study of Roman to Frankish monuments in Turkey as well as his interest in Genoese monuments on Chios, R.M. Dawkins’ study of Greek dialects in Cappadocia and the Pontus, K.T. Frost’s interest in traditional boats on the Euphrates, W.S. George’s drawings of the Acropolis and other subjects. Below are examples of two other independent travels and studies. Walter Leaf (honorary Treasurer of the BSA, 1886-1906) made a detailed exploration of the area around Troy with the aim of understanding Homer’s geographical knowledge which he published in 1912 as Troy: a study in Homeric Geography. The other is F.W. Hasluck’s travels to the monasteries of Mount Athos were described in a previous Archive Story (F.W. Hasluck and the Monasteries of Athos). All of the photographs on the boards below appear in the SPHS collection.

Special Studies

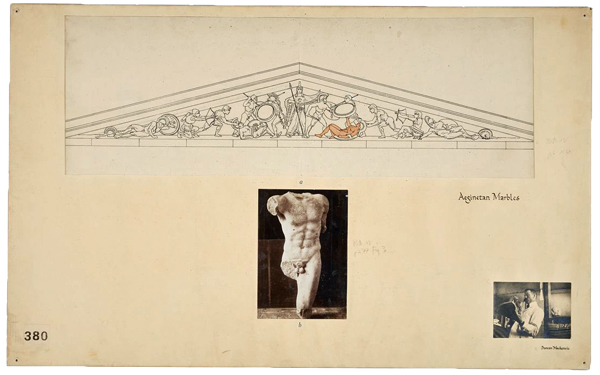

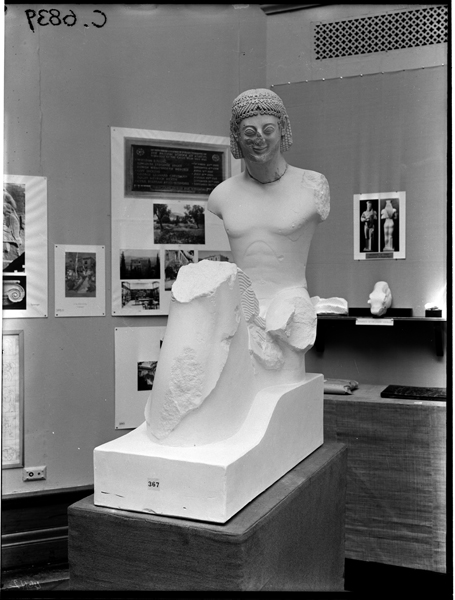

Generally this section dealt with studies in pottery, sculpture and architecture – the traditional subjects of archaeological research in the Classical World at the time. Many BSA students engaged in the study of these subjects, as reflected in the long list of displays: Geometric pottery from Crete (Miss M. Hartley), Pottery from Naukratis (Miss H. Lorimer), Pottery and terracottas from the Rhitsona cemetery (R.M. Burrows and P. Ure), reproduction of the ‘Macmillan Vase’, Drawings of Archaic art (H. Payne), sculpture from Thasos (J. Penoyre), votive terracotta reliefs in the Acropolis Museum (Miss C.A. Hutton), Greek sculpture (A.J.B. Wace and F.W. Hasluck), sculpture from Kynosarges excavated by the BSA in 1896, reconstruction of the chest of Kypselos (H. Stuart Jones), and Restoration of a sculpture group by Damophon (G. Dickins). There were two further studies illustrated below: the reconstructions of the ‘Rampin’ horseman from the Acropolis (H. Payne) and the east pediment sculptures of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina (D. Mackenzie). All of these studies had been published either in the Journal of Hellenic Studies or in the Annual of the British School at Athens.

BSA SPHS 01/6830.C6839. The Acropolis horseman replica with the ‘Rampin head’ displayed in the gallery space

The British School at Athens

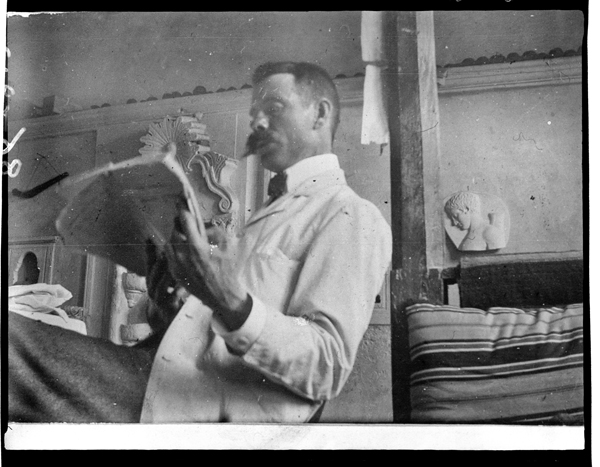

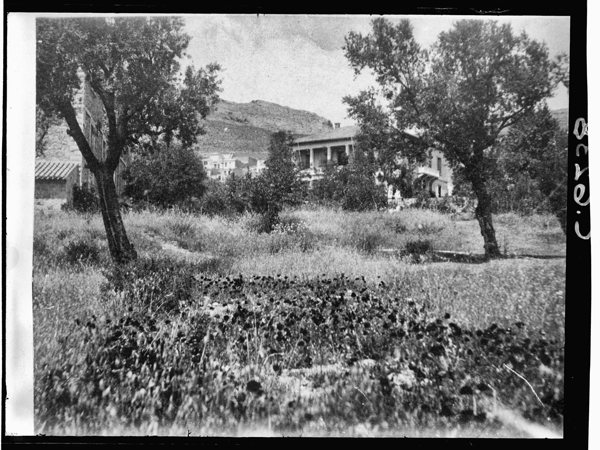

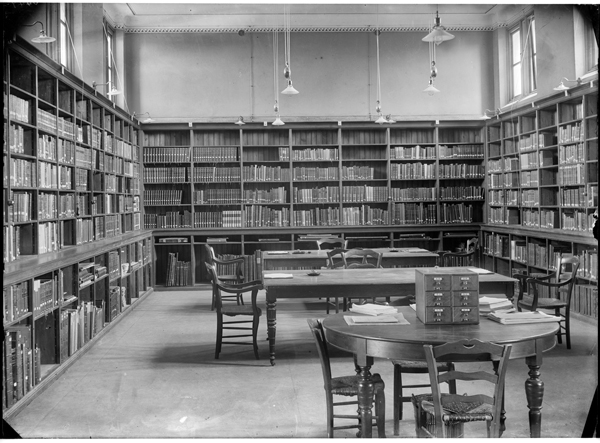

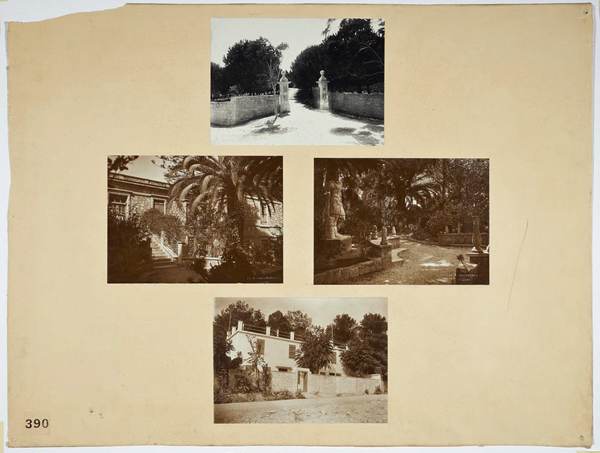

Images of the BSA can be seen behind the Rampin Head in the gallery space in the image above. This section was designed to show the exhibition goers the Institution where much of the research originated. The largest photograph was of the War Memorial commemorating seven students lost during WWI – a poignant reminder that also accentuated the human side of the institution. Photographs of the Athens buildings (the Director’s House, the Hostel and Library) in Athens were shown. Notably, in the caption for the Penrose library, the BSA made the direct appeal for donations to extend the library. An entire board highlighted the newly acquired premises at Knossos. A portrait book of Chairmen, Directors and other Officers of the BSA was displayed in front of the mounted photographs and boards.

Studies in Modern Greek Life

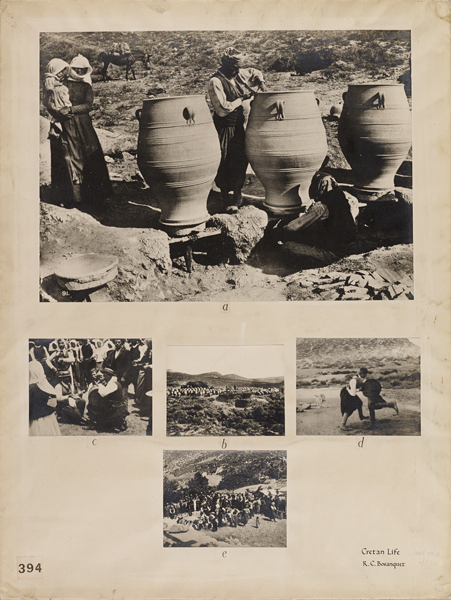

Modern Greek life, akin to ‘ethnography’, formed a part of BSA life. Observations on modern day activities were often seen as relics of past practices (see Archive Story: Relics of the Past). Sometimes there were incidental recordings of traditional life made during the course of archaeological exploration and sometimes specific studies revolving around a particular theme. During R.C. Bosanquet’s excavations on Crete – particularly at Praisos and Palaikastro – he recorded what he thought were interesting aspects of Cretan life: pottery production and traditional festivals. These activities resonated with past practices hinted at in the archaeological record. Similarly, A.J.B. Wace and R.M. Dawkins expressed an interest in traditional mumming plays – Wace in the Pelion and Dawkins in Thrace – concluding that the plays contained relics of Dionysiac rituals. Other boards included ones detailing the travels (and textile collecting) of Wace and Dawkins in the Dodecanese and Cycladic Islands (see Archive Story: Island Observations) and the journey to the Vlach village of Samarina by Wace and Thompson which resulted in their 1914 book, The Nomads of the Balkans.

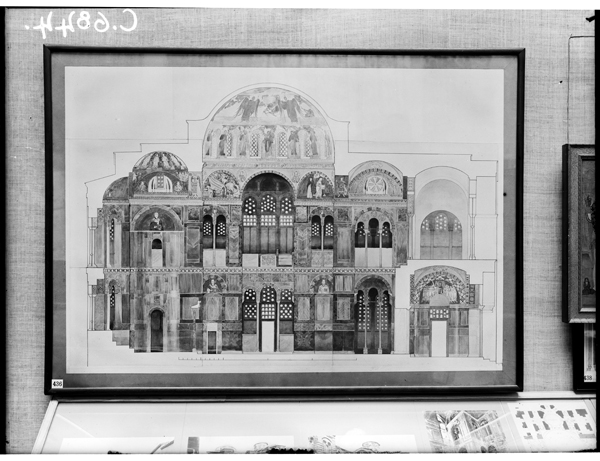

IV. Byzantine

Byzantine research was embedded in British School at Athens as early as 1887 when architectural students R. Weir Schultz and S. Barnsley arrived to carry out a study of some of the Byzantine churches of Athens. This tradition continued, often with aid from the Byzantine Research and Publication Fund. Scholars at the BSA were engaged in Byzantine studies – primarily in the architecture of ecclesiastical buildings, but also in the frescoes, mosaics, icons and other related objects. The West Room of the Exhibition space at the Royal Academy was devoted to Byzantine Studies. Numerous drawings of churches were exhibited: from Athens, the Monastery of Hosios Lukas (Phocis), the Monastery of Daphni (Attica), Mistra (Laconia), Arta (Epirus), Zoodokos Pege in Samari (Messenia), churches in the Argolid and in Thessaloniki, and outside Greece in Palestine. Decorative arts were represented (both secular and sacred) and consisted of pottery, carved ivory or bone panels, medallions, jewellery, silver spoons, flasks, crosses, etc. Special cases were devoted to Byzantine Icons. Also in this section was a display of traditional Greek textiles, lent from the collections of Liberty & Co., R.M. Dawkins and A.J.B. Wace.

BSA-SPHS_01-6835.C6844.Section drawing of the Great Church of St. Luke in Stiris mounted on the wall in the gallery space

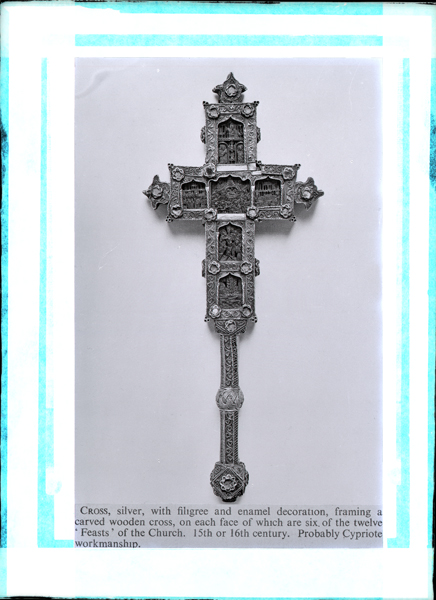

BSA SPHS 01/6819.C6828. Silver filigree cross with enamel decoration, framing a carved wooden cross, on each face of which are six of the twelve ‘Feasts’ of the Church. Possibly Cypriot, 15th or 16th century

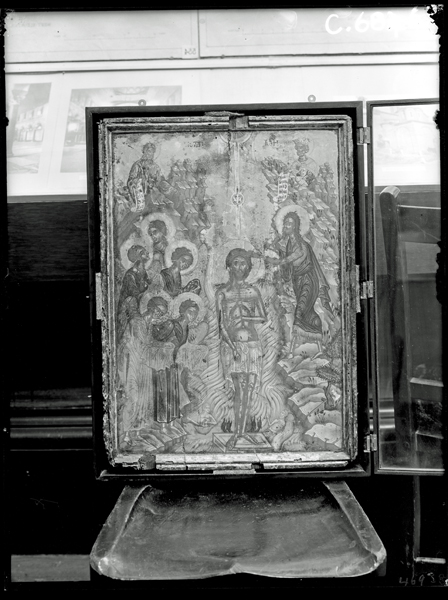

BSA SPHS 01/6837.C6846. Byzantine icon of the Baptism, Cretan school, 16th century. Shown in the gallery space.

* * *

More than 12,000 people visited the exhibition (BSA Annual Report 1936/1937). Among those thousands was the 14 year old schoolboy Michael Ventris. His introduction to Arthur Evans and first-hand observations of the Linear B tablets at this Exhibition made a lasting impression on the person who would later decipher the script. The decipherment alone, now celebrating its 70th anniversary, made a deep impact on Aegean studies, and may have had its initial spark in 1936 with the observations of a 14 year old school boy. Indeed, the Exhibition exposed the public to Evans’ vision of his Minoans as well as the vast array of work conducted by the BSA and its members – valuable intangible benefits.

However, the immediate tangible goals were less rewarding. The financial report for the 1936/1937 year indicated that ‘the revenue account of the Exhibition shows a debit balance of £212 14s. 8d. of expenses over receipts’. Yet, the next year’s financial report showed an increase in donations, and the direct appeal for the extension of the library must have borne fruit as the large Payne Room attached to the library was built in 1937. The increases were short-lived, however, due to uncertainties of the approaching war, something that could not have been foreseen by the Exhibition committee.

We might ask the question: was the Exhibition a success? Amara Thornton concludes her analysis on the ‘Exhibition Season’ by indicating that these archaeological exhibitions in London served to cement relationships between archaeologists and the organisations or groups that supported them. This was achieved by inserting displays of archaeological activities into the London social and cultural calendar ‘within reach of that most valuable commodity – the public imagination’. In other words, the intangible benefits outweighed and outlasted the immediate tangible ones.

Deborah Harlan

British School at Athens

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Further Reading

British School of Archaeology at Athens, 1936. British Archaeological Discoveries in Greece and Crete 1886-1836: Catalogue of the Exhibition. London: Royal Academy of Arts.

Evans, A.J. 1921-1935. Palace of Minos at Knossos. London: Macmillan & Co.

MacMillan, G.A. 1910. ‘A Short History of the British School at Athens, 1886-1911’, Annual of the British School at Athens, 17, pp. ix–xxxviii.

Thornton, A. 2015. ‘Exhibition Season: Annual Archaeological Exhibitions in London, 1880s-1930s’, Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 25(2), pp. 1–18.