J.T. Wood’s Ephesus through the lens of Corporal J. Trotman: Archive Images in the BSA SPHS Collection

An interesting story began to take shape when cataloguing a series of 67 large glass plate negatives housed in the BSA-SPHS collection, originally part of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies photographic library. According to the original negative register, they were donated to the Hellenic Society by a Mrs Trotman. The images were of Ephesus and other ancient cities in Asia Minor. In addition, several of the photographs contained images of sailors from the H.M.S. Caledonia at Ephesus. Having these few clues to go on, I began looking into the story of these photographs.

In the 1892 ‘Proceedings of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies’, there is a reference to images of Ephesus and the Seven Cities of Asia Minor taken by Mr J. Trotman being made available to the members of the Society through the Autotype Company, a commercial publisher that specialised in reproducing fine art photographs. This same offer was made for groups of Greek photographs by William Stillman, Walter Leaf and R. Elsey-Smith. By 1902, it can be documented images originally managed by the Autotype Company were housed in the Hellenic Society’s growing negative reference collection in a list produced for that year’s ‘Proceedings’.

This explained how the images came to be in the collection, but who was Mr J. Trotman? Thanks to a fully searchable online 1877 publication of J.T. Wood’s Discoveries at Ephesus, Trotman and his photographs began to tell their story. On 9 January 1872, three sappers from the Royal Corp of Engineers were sent to help Wood excavate the newly discovered Temple of Artemis at Ephesus. Two of these sappers didn’t work out and were sent back, but the third was Corporal Trotman. Trotman would remain at Ephesus for the next three years, joined by another sapper (Sargent McKim) in his second year.

At this point, when Trotman came on the scene, Wood had been working at Ephesus for a little under ten years, excavating around the Gymnasium (originally thought to be the site of the Temple of Artemis) and exploring other areas of the ancient city including the Forum, ‘Baptismal Font’, the Odeum, the Port, St. Luke’s Tomb, the Theatre, Magnesian and Coressian Gates, and the Stadium.

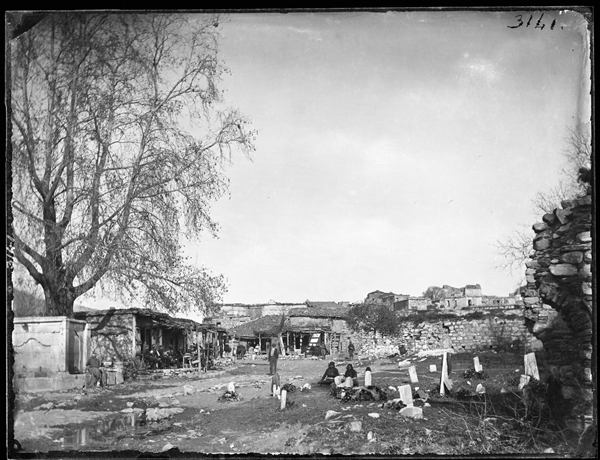

Although Trotman’s images date from 1872 and 1873, they evoke the life Wood describes while working earlier at Ephesus. In 1867, Wood described the present state of Ayasalouk, the nearby village on the hill above Ephesus which is captured in one of Trotman’s images.

At the present time there are at Ayasalouk a few caffigees and bakals [coffee-house keepers and provision dealers], whose numbers were largely multiplied while the excavations were in progress. But although there are many small houses and huts at Ayasalouk, there are not more than twenty regular inhabitants, the houses being occupied only during the sowing and harvest time by the people from Kirkenjee, who cultivate the land in the plain of Ephesus and now grow tobacco amongst the ruins of the ancient city. (Wood 1877: 14)

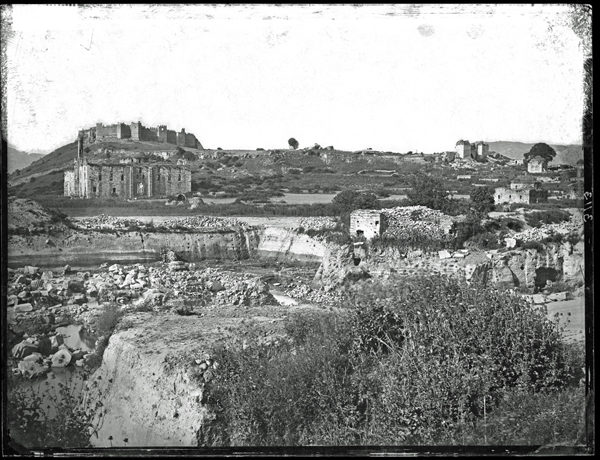

The excavation house was located near the rail station, outside of the village near the old aqueduct. One of Wood’s remarks on this accommodation is its noisy storks in the spring of 1870, again is shown in one of Trotman’s images.

The first stork appeared on one of the piers of the aqueduct at Ayasalouk. It was soon followed by others, till every pier was occupied by a pair. Sometimes a quarrel took place, and there was a fight for the possession of a pier, for the sake of perhaps of the old nest, which they leisurely built up again with sticks and twigs brought from the surrounding fields. The lazy birds spend quite a fortnight in building their nests. (Wood 1877: 160-1)

Left: BSA SPHS 01/1193.3108: Railway near Ayasalouk with excavation house highlighted. Right: A close-up of the back of the two-storey excavation house near the railway and the piers of the aqueduct with stork nests

Wood also describes his excavation of the Odeum in 1864, which he had found to be in perfect condition. Afterwards, it was badly vandalised by visitors by breaking off fragments of marble from seats and cornices.

One day after the Odeum had been cleared out, a party of about thirty people came while I was there and began throwing the marbles about. I could not look on and forbear speaking; and what I said was uttered in so fierce and threatening a manner that it stopped further destruction by that party. The desire to possess fragments of ancient sculpture, such as a nose, an ear, a finger, or a morsel of architectural moulding from an old building, may be natural, but is most deplorable when it causes, as it often does, the utter destruction of the works of art… (Wood 1877: 63)

Another of Trotman’s images shows the Baptismal Font described by Wood. Unlike the Odeum, it is probably shown in the same condition as Wood left it after his investigation.

Digging in the Forum, I found on the east side, what I believe to have been a baptismal font, a large basin, 15 feet in diameter, raised upon a pedestal; the basin consisting of one solid mass of breccia. This, I presume, was used in early Christian times … for the public baptism, in large groups, of converts to Christianity. It is so formed that a full-grown person might, without difficulty, climb over its smooth, rounded edge, and stand in water 9 inches deep, while the baptiser could stand dryshod in the centre which was apparently raised for that purpose. (Wood 1877: 31-2)

It wasn’t until the season of 1868-9 that Wood found the peribolos wall of the Temple of Artemis. He began systematically excavating the following year with a few workmen, finally discovering the temple at the end of 1869. For most of the 1870-1 season Wood was beset with rain and could only recruit a small workforce. Wood delivered a lecture in London on the temple in July 1871 which would secure further support from the British Museum Trustees. As an aside, it is interesting to note that the lively discussion after Wood’s lecture included F.C. Penrose who, fifteen years later, would become the British School’s first director.

Trotman’s images also tell the story of the excavation of the Temple of Artemis, although he was not officially appointed as an excavation photographer. Wood does not seem to have systematically photographed work in progress, although he does mention an Armenian photographer from Smyrna arriving to photograph a column base. One of Trotman’s first acts as an army engineer on the site of the Temple of Artemis was to pump water out of the excavation which had become waterlogged at the close of the previous season. In his photograph below, it is possible to see the standing water.

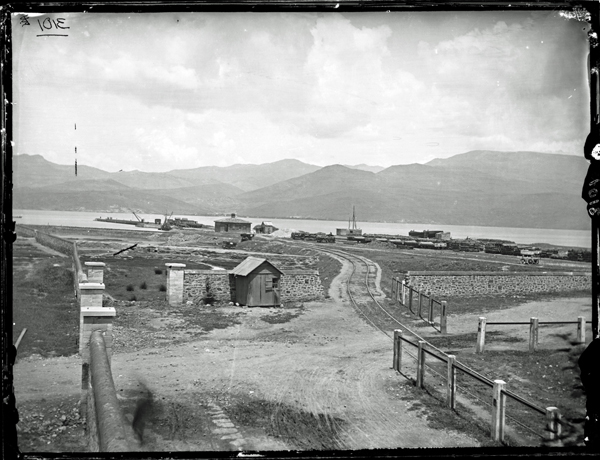

Throughout his exploration of the site, Wood was largely financed by the British Museum. The terms of his firman allowed him to export antiquities, leaving duplicates for the Turkish Government. Prior to discovering the Temple of Artemis, several British naval ships were sent to Smyrna to transport antiquities from Wood’s excavations in Ephesus back to London. And, at the end of 1871, the H.M.S. Caledonia arrived, allowing Wood to expand his workforce with members of the crew. A few months later Trotman arrives and captures some of the crew in photographs.

BSA SPHS 01/1217.3132: Officers and sailors of the H.M.S. Caledonia. Captain Lambert lent members of his crew – Lieutenant McQuhae, Lieutenant Gambier, Dr Farr and sailors

Antiquities were transported from the site by rail to Smyrna, a three-hour journey away. Interestingly, this railway also connects Wood to Ephesus. In 1858, Wood received a commission to design railway stations for the Smyrna and Aidin Railway which first brought the site of Ephesus to his attention. With antiquities bound for the British Museum in London, the H.M.S. Caledonia left port on 1 February 1872.

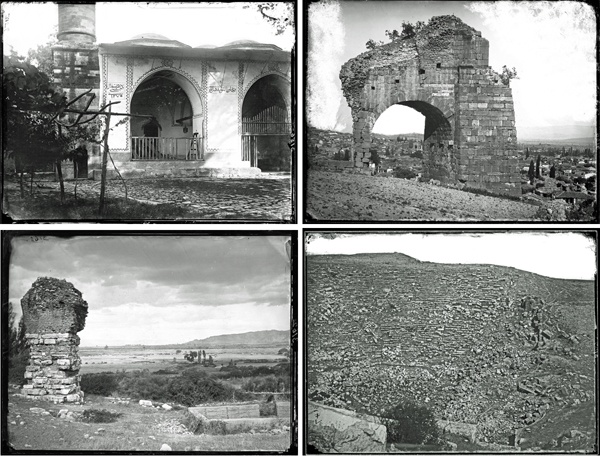

At the end of his second season at Ephesus, Corporal Trotman spent the summer months of 1873 photographing other sites in Asia Minor – the ‘Seven Cities’ – significant for their early churches mentioned in the Book of Revelations. He visited Laodicea, Philadelphia, Sardis, Smyrna and Pergamon.

Top. Left: BSA SPHS 01/1240.3156: Philadelphia: Christian church converted to a mosque. Right: BSA SPHS 01/1250.3166: Pergamon: West Gate. Bottom. Left: BSA SPHS 01/1246.3162: Sardes: View from the church looking E showing the plain. Right: BSA SPHS 01/1231.3147: Laodicea: Large theatre

Although Trotman suffered ill health after the summer of 1873, he remained working for Wood at Ephesus until his final departure on 27 March 1874. Near the conclusion of Discoveries at Ephesus, Wood mentions that many of the photographs taken by Trotman at this time helped him produce woodcuts and lithographs to illustrate the volume. Commercially viable halftone reproduction of photographs in publications would not available until the 1880s. For example, the village of Ayasalouk (BSA SPHS 01/1225.3141) shown above appears as a woodcut illustration opposite page 170. Another is the Ayasalouk mosque near the rail station shown in BSA SPHS 01/1214.3129 below.

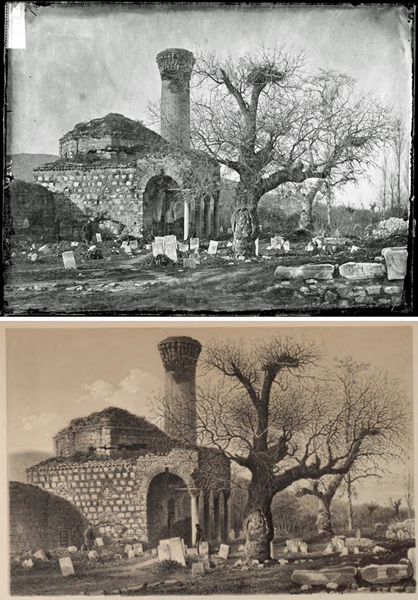

Top: BSA SPHS 01/1214.3129: Small Mosque at Ayasalouk. Bottom: J.T. Wood 1877. Discoveries at Ephesus. woodcut illustration opposite p. 162

Nearly every detail is exact with the removal in the woodcut of the seated man smoking a pipe in the porch of the mosque. Both, however, include the possible figure of J.T. Wood by the side of the mosque, but only becomes clear in the photograph.

Wood left Ephesus for the last time shortly after Corporal Trotman. He later sends in his report to the Principal Librarian of the British Museum with fulsome praise for the two sappers.

I cannot speak too highly of their conduct and the assistance they have unremittingly and invariably given me, or of the intelligence and assiduity with which they have carried on the works under my direction. They fully deserve the reward that may be accorded them, for they have exhibited the utmost patience and fortitude under the trying occupation in which they have been engaged. (Wood 1877: 283)

Wood goes on to say that they have both left the army – McKim to become a carpenter and Trotman to be an attendant in the Metal Room at the British Museum. Trotman, possibly though his association at the British Museum, was aware of the formation of the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies in 1879 of which J.T. Wood was listed as a founding member. This was only five years after their return from Ephesus and only two years since the publication of Wood’s Discoveries at Ephesus in 1877. One of the objects of the Society, laid down as rules from the very beginning was to collect images of the Hellenic World, a ideal home for Corporal Trotman’s photographs.

Deborah Harlan

Honorary Research Fellow

Department of Archaeology

Sheffield University

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

For further reading:

Wood, J.T. 1877. Discoveries at Ephesus including the Site and Remains of the Great Temple of Diana. London: Longman, Green & Company