Surveying Thasos: J. Baker Penoyre’s Photographs in the SPHS Image Collection

In late June 1907, the archaeologist John Baker Penoyre landed on the northern Aegean island of Thasos. It was his intention to survey the ancient remains on this pine-wooded island. During the next five months, Penoyre and his Cretan gendarme companion, Ali Ismail, systematically documented remains of all periods throughout the island which included plans, elevations, sketches and photographs.

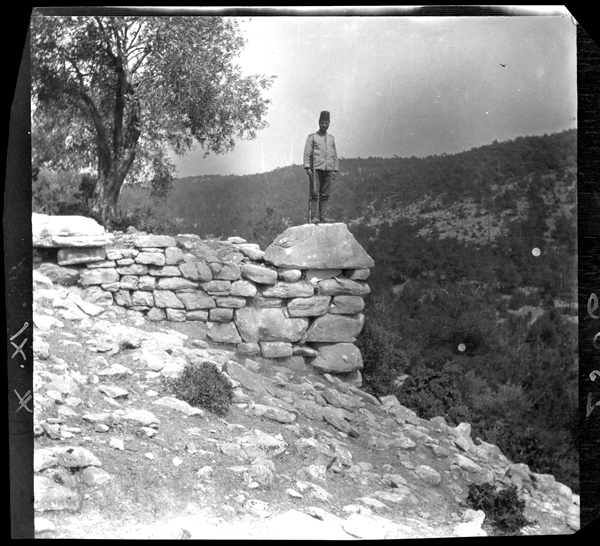

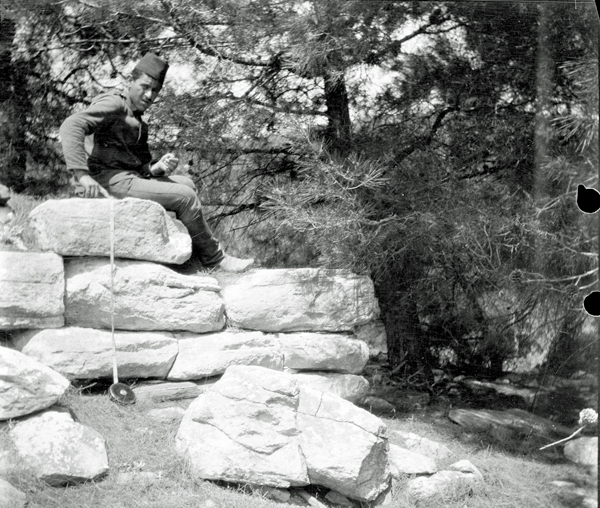

BSA SPHS 01/0888.2510. The site of Ayios Ioannis on Thasos with Ali Ismail on a wall with a tape measure.

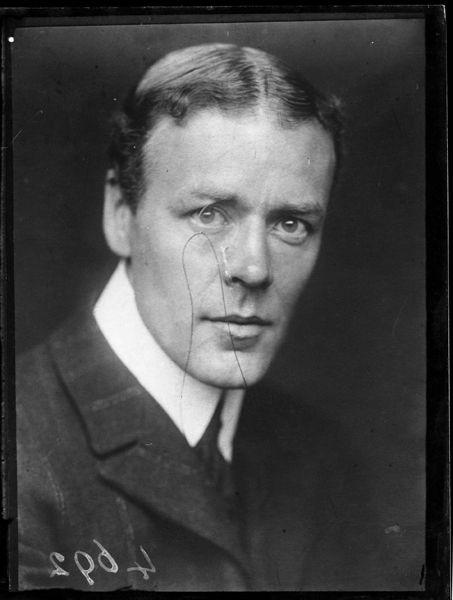

John Penoyre was associated with both the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS) and the British School at Athens (BSA). He had been a student at the BSA from 1900-1901 and thereafter became the Secretary and Librarian for the SPHS, a position he held until 1936. Coincidentally, this meant he was also responsible for the SPHS photographic library. Penoyre also retained a close association with the BSA as its London-based Secretary from 1904-1912.

In 1907, Penoyre applied and was granted a year’s sabbatical from these duties which enabled him to travel in Greece. He visited the BSA’s excavations at Sparta (in its second year of excavation) before heading north to visit Thessaloniki, Kavala and travel with F.W. Hasluck in the region around the ancient city of Cyzicus (a subject of a previous Archive Story: The Cyzicus Question).

BSA SPHS 01/0737.2324. Sparta, Artemis Orthia: S.E. Corner of the Artemision Temple (with R.M. Dawkins? in centre) taken by Penoyre in 1907.

BSA SPHS 01/0724.2310. Sangarius (Sakarya) River, West Side of the Justinian Bridge. Taken in 1907 by Penoyre during his travels with Hasluck.

Penoyre was not the first British archaeologist to explore Thasos. Two decades before, in 1887, Theodore Bent, spent seven weeks exploring the island funded by the SPHS and the British Association for the Advancement of Science (BAAS). Bent concluded his investigations with a brief excavation at the south coast site of Aliki, the source of the famous Thasiote white marble. His observations were promptly published that same year as short notes in The Aetheaum, The Classical Review and in a letter quoted in ‘Archaeological News’ published in The American Journal of Archaeology and of History and of the Fine Arts. Also in 1887, Bent’s comprehensive description of ‘The Ancient Marble Commerce of Thasos’ appeared in the Report of the 57th Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In addition, an article co-authored with E.L. Hicks of the British Museum was published in the 1887 Journal of Hellenic Studies (JHS) that catalogued Thasos inscriptions (most of which came from the site of Aliki). The article mentioned that Bent was prevented by the Ottoman authorities from removing the inscriptions from the island.

Penoyre’s survey of the island was meticulous and provided a better record than Bent’s cursory investigation. The manner in which these two British archaeologists conducted their surveys reflected changing methods of investigation from the 19th to the 20th century: from explorations based on historical texts, geared towards the acquisition of antiquities to methodical surveys aimed at mapping and the recording of monuments in situ. On the few occasions that Penoyre refers to Bent in his publication, it is to mention a missed inscription or to question his descriptions or interpretations. Nor does Penoyre mention Bent’s 1902 sensational announcement in The New York Times of his identification of the tomb of Gaius Cassius Longinus on Thasos.

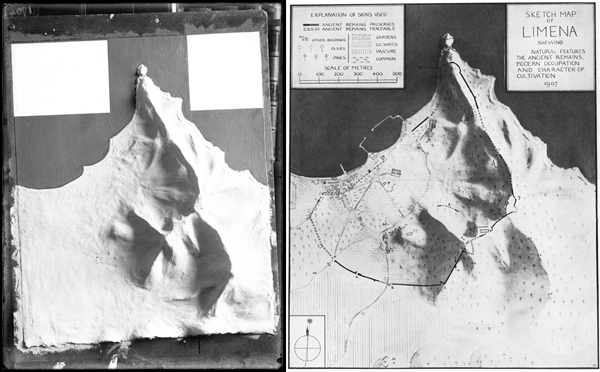

From Penoyre’s account, it seems the primary focus of his survey was to record the layout of the ancient town known as Limenas, the port (or harbour) and capital city of Thasos. Parts of the ancient city can still found throughout the modern town and the archaeological remains date from the Archaic to Medieval. He even produced a 3D model of this part of the island, photographed it in raking light and annotated it in his publication to show the relief around the city of Limenas.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/0389.1702. Thasos, Limenas: Model of Mountain System lighted from East. Right: Annotated image of the model showing current state of Limenas, both modern and ancient in relation to natural features. (Penoyre 1909: pl. XIV).

Penoyre paid particular attention to the acropolis: the circuit walls, gates and structures, including sculpted remains. For scale, many of Penoyre’s images use the distinctive figure of Ali Ismail and the ubiquitous walking cane (or an occasional rifle) propped up against walls.

BSA SPHS 01/0797.2420. Limenas: City Wall, Southeast angle gate, northern half, from within with a walking cane for scale.

BSA SPHS 01/0823.2446. Limenas: Stele outside the South wall where the path to Panagia crosses, showing whole stele.

Penroye started from Limenas and proceeded around the island, conentrating on three areas. The first was the Kinara area along the east coast of the island with its numerous Byzantine chapels and evidence for Classical remains. and then to the south to Aliki (the city excavated by Bent in 1887) and the adjacent area to the west of Astris at the southern most point of the island with abundant evidence for fortresses and towers.

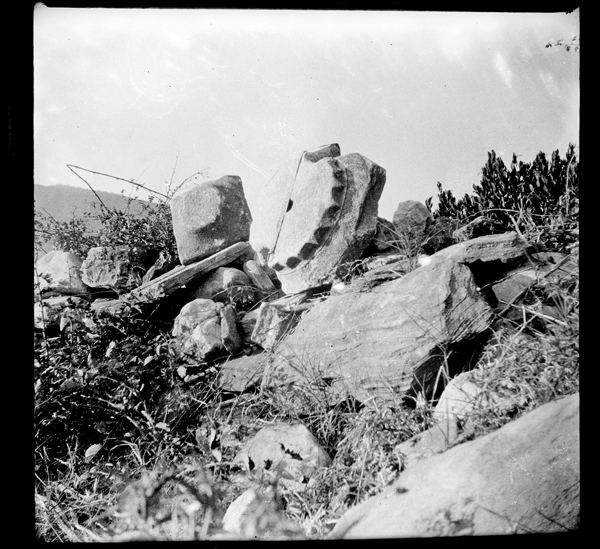

Penorye then proceeded north, along the west coast with an occasional foray into the interior, ending as he started at the port town of Limenas. During his survey Penoyre noted the disruption and decay of many of the remains. Some were caused by Bent’s ‘excavations’ (which Penoyre places in inverted commas), by treasure hunting locals, or simply caused by the weathering effects of time. In one instance, he photographed a sarcophagus that he reported had recently been wrecked by dynamite which you can see in his photograph below.

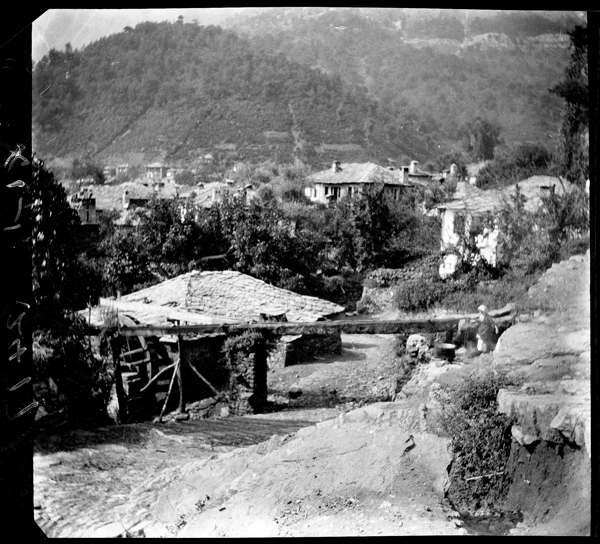

Penoyre also observed everyday life among the villagers of Thasos which he captured with his camera. In the image of the village of Potamia, Penoyre shows the watercourse, part of a waterwheel and roofed space for for the village ‘hammer mill’ style clothes washing facility in the foreground with the village behind. From the photograph of the lower spring at Panagia, it is apparent the women, surrounded by chickens, children and a dog, are collecting water in pots although this activity is not reflected in its caption. At Maries, Penoyre photographed a wooden semantron, a percussion instrument used in the Eastern Orthodox church, perhaps as curiosity. At Bulgaro (modern Rachoni), he captured the blessing of food for a festival from a position outside the activity. Taking ethnographic images – consciously or unconsciously – was not an uncommon occurrence by such Western observers. Although the objects or activities portrayed often played little part in their subsequent discussion of antiquities – the primary purpose of their fieldwork or travels.

Soon after the completion of the survey, negatives of the Thasos Survey were deposited in the growing SPHS photographic collection. Only a few of the images from Thasos – primarily inscriptions and the Classical remains of Limena – were reproduced as lantern slides for the loan collection. As we have seen with past archive stories on the SPHS image collection, the SPHS photographic library was often used as an archive repository for fieldwork images. The BSA as an institution and many of its scholars such as F.W. Hasluck, A.J.B. Wace, R.M. Dawkins and D.G. Hogarth regularly deposited images they took during various explorations, surveys and excavations. The primary reason images were reproduced in slide format was for teaching, something for which many detailed images documenting fieldwork were generally not suited. Instead, the dissemination of these sorts of images was through academic publication.

The resulting island-wide survey of Thasos was published in two long articles in the JHS in 1909 – one concentrating on the survey results and the other on inscriptions (co-authored by BSA scholar Marcus Tod). Both articles were illustrated with a selection of Penoyre’s photographs (42 of which are contained in the BSA SPHS collection). The survey article included numerous plans and sketch maps. Put together with the remainder of unpublished images in the BSA SPHS collection, they provide a picture of the island and its remains in the early 20th century.

Deborah Harlan

British School at Athens

Images from the BSA-SPHS collection are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

For the survey photographs, select Thasos Survey 1907 in Collection Events of the Advanced Search menu.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Further Reading:

Baker-Penoyre, J. and M.N. Tod 1909. ‘Thasos’ Journal of Hellenic Studies 29: 91-102.

Baker-Penoyre, J. 1909. ‘Thasos (Continued)’ Journal of Hellenic Studies 29: 202-250.