Philhellenism redux- Finlay rises

‘We are all Greeks’ wrote Percy Shelley in 1821[1], in what became a rallying cry for all those Romantic revolutionaries— known to us as the Philhellenes—who lent their support in one way or another to the ‘Greek cause’, i.e. the Greek Revolution. Indeed, it is almost impossible for one to think of the Greek Revolution without the Philhellenes, both those who left their homes to fight in Greece and those who supported the cause from the many ‘home fronts’ that were set up from the very beginning of the revolution. And yet, we are still far from understanding exactly what motivated many of those people to join the revolution and put their lives on the line for somebody else’s war. Why would, for example, a Scot from Glasgow, who was studying law at Göttingen, decide to join the Greeks? Or, even more bewilderingly, an English ex-navy officer? What made such people transform a vague sense of sympathy for the Greeks to an active involvement in their war? And how did this involvement develop over the course of the war?

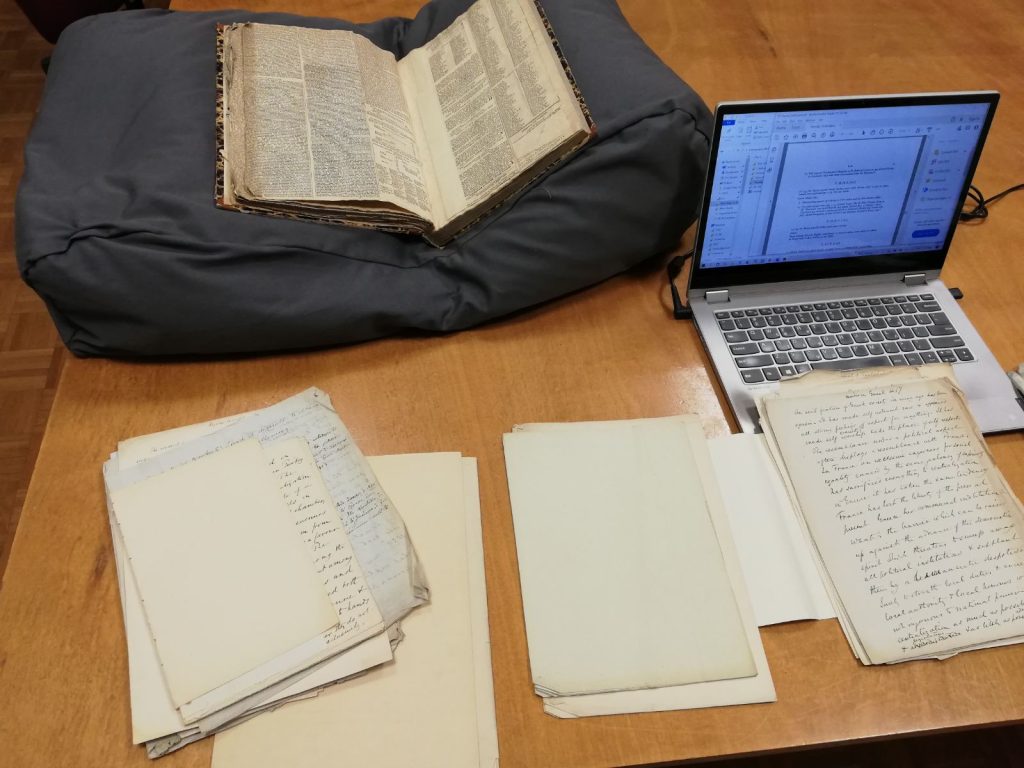

These are some of the questions that lie at the heart of the British School at Athens (BSA) research project, Unpublished Archives of British Philhellenism During the Greek Revolution of 1821, taking place in collaboration with the National Library of Greece (NLG) and generously funded by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation. Members of the research team are the undersigned (as the Research Fellow), Felicity Crowe (the Project’s Archive Assistant), Amalia Kakissis (the BSA Archivist), and last but not least, Roderick Beaton, the mentor of it all.

The project concentrates on the London Greek Committee papers (held by the NLG) and, in particular, on those of George Finlay (the Scot in Göttingen) and Captain Frank Abney Hastings (the English ex-navy officer) that are part of the Finlay collection held by the BSA. Hastings and Finlay were not only eyewitnesses and participants to many of the events of the Revolution, but, in fact, they dedicated the remainder of their lives to Greece. Hastings until 1828, when unfortunately he would die in battle, and Finlay until 1875, when he would die in Athens, his home after the end of the revolution.

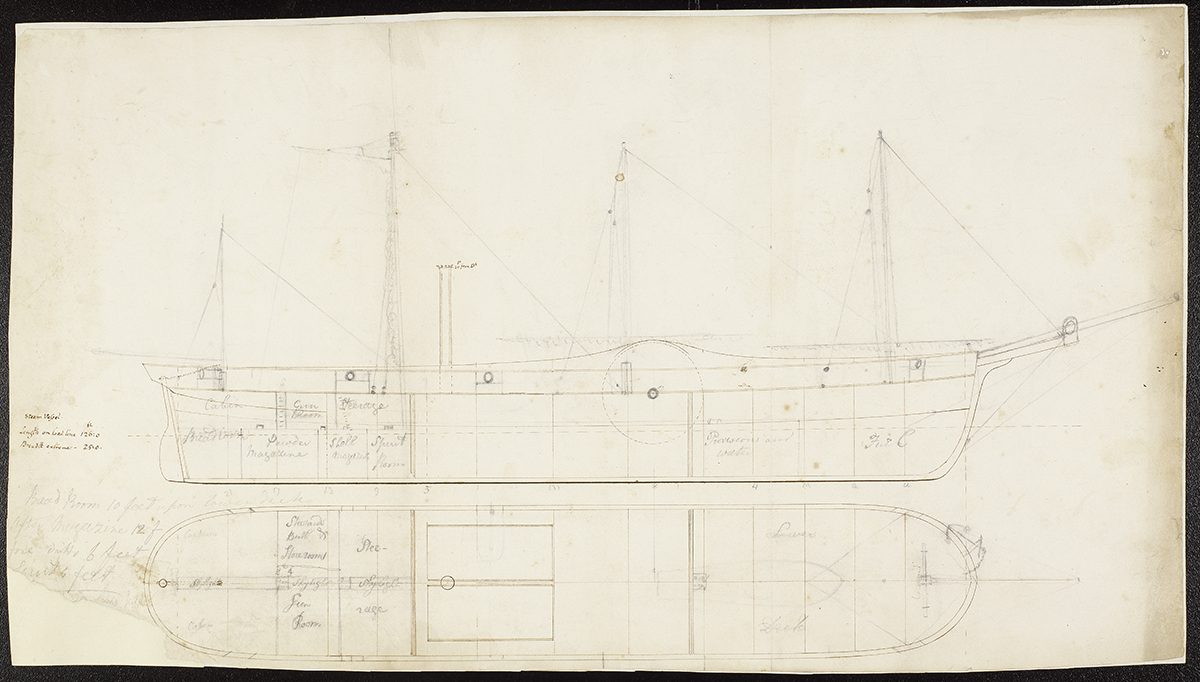

That said, the careers and lives of these two close friends could not be more different. A man of the seas and the best Navy (British) in the world—as he told Richard Church[2]–Hastings would come to Greece in 1822 after his dismissal from the Royal Navy. Although initially thought to be an English spy, Hastings’ directness and uncompromising manners quickly cleared any doubts about his intentions. His naval expertise, first shown off the shores of Chios on board the Themistocles of the Tombazi brothers and later on his own ship (the first steam-powered warship, the Karteria) won him respect from Greeks and Philhellenes alike.

Pencil drawing of the Karteria in the Frank Abney Hasting Papers which are part of the George Finlay Collection, FIN/H/3

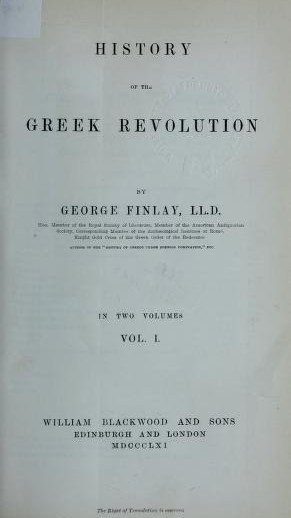

George Finlay first came to Greece in 1823. Essentially a man of letters, he was involved in many things revolutionary but very little of that in military action. He made many good friends, but also many enemies both during the Revolution and after. Never afraid of criticising others, including men of status (not least King Otto himself), and always thinking of the revolution as an event of global significance, Finlay would write a two-volume History of the Greek Revolution (1861), widely regarded ever since, as one of the fullest and most authoritative accounts of the conflict.

But why Greece?

Why did Finlay and Hastings come to Greece and fight for the ‘Greek cause’ in the first place? This question isn’t as simplistic or easy to answer as it may seem. In fact, neither Finlay nor Hastings ever addressed the issue directly. In Hastings’ case things seem more straightforward. In search of active service, he probably saw in the Greek revolution a noble cause, a place where he could restart his career, and an opportunity to implement his innovative ideas on naval warfare.

Lithograph of George Finlay wearing the medals he was awarded for taking part in the Greek Revolution, FIN/GF/A/20

But what about the young student of law, George Finlay? Under what circumstances did he decide to come? When and how, did feelings of sympathy turn into action? Interestingly enough, no matter how much Finlay wrote during his lifetime, he never told us why he came. Or to be more precise, he did not go public with it.

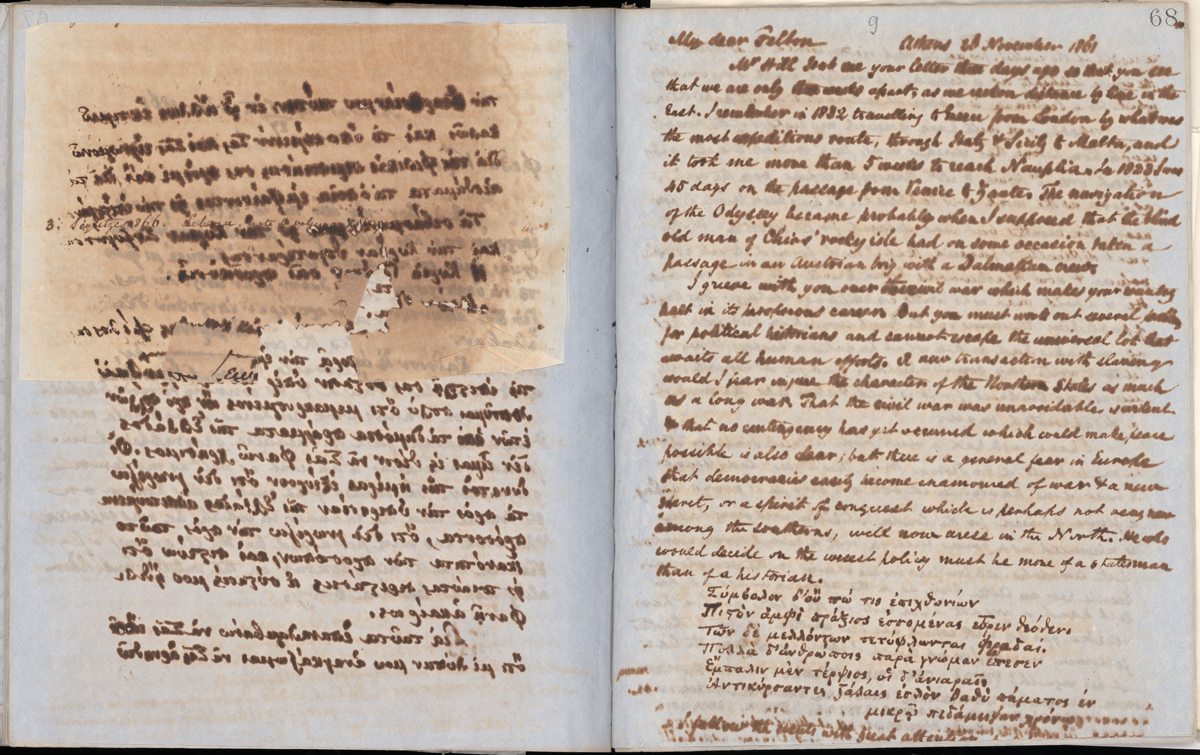

Silences is not something unexpected for historians. In fact, part of the excitement of doing history is the effort to understand what is not told in the sources. That said, of course, we are more than happy when in trying to connect the dots, we are offered a little help from our ‘friends’—those we are investigating. While going through Finlay’s papers in trying to assess them for the BSA project, I came across a black cloth volume, that was full of ‘carbon’ copies of letters (in rather poor condition) sent by Finlay to several people. Within the volume, I found a note in which Finlay talks about himself.[3]

Interestingly enough, the note is written in the third person and is part of a letter he sent to C.C. Felton (President of Harvard University at the time and a distinguished professor of Greek). In other words, here we have Finlay writing to Felton about a man called George Finlay. Could this be an act of timidity or of professionalism on the part of Finlay the historian? Whatever the case may be, Finlay offers in this letter important information about himself and his decision to come to Greece.

After giving some details of his family origins in Glasgow and his birth in Faversham in Kent, we learn that, following his father’s death (an ex-major of the Royal Engineers, who worked as an inspector of the government powder mills), his mother married a merchant, a certain Mr. McGregor, and they lived in Argyllshire. This was also when Finlay the historian seems to have been born, as ‘George always cherished his love of history to the lessons of his mother while he was a child as she used to read to him the history of England and explain it in such a way as to render it more interesting than any nursery tales’. But Finlay the liberal was born later, after his parents moved to the U.S. in 1810 and sent young George to live with the family of his uncle Kirkman Finlay (an M.P for Glasgow). It was Kirkman that would instill the first liberal sentiments in George, the love for books but also the importance of practical life. Indeed, it was he who would discourage George from following a career in the army, not least because ‘it was no profession in times of peace for one who possessed only his yearly fortunes’. Kirkman then thought more suitable a career in law managing to place George as a sort of clerk in the Glasgow legal firm of Graham and Mitchell, with the former being, according to Finlay, a ’man of superior talent, great legal knowledge and most liberal opinions’.

The next step for Finlay was Göttingen and Roman law (read civil law). This should come as no surprise. German universities in this period were considered the best in the world, and Roman law the mark of high intellectualism and of progressivism. As trade of the British Empire was expanding this was also a step towards a career in contract law. But as Finlay informs us, during his studies in Göttingen, ‘his attention has been […] strongly diverted to the breaking out of the Greek Revolution’. This would have remained a simple diversion, if it wasn’t for… who else? His uncle Kirkman. It was he, who when George was back in Glasgow, saw through the young man, and to use Finlay’s words, ‘he was more acquainted with his [George’s] mind than he was himself’. ‘Well George, I hope you will study hard (?) at Roman law’, Kirkman told Finlay according to the latter, ‘but I suppose you will visit Greece before we see you again’. And yet, Finlay was slow to actually pay that visit. It was not ‘until 1823 that he [George] resolved to visit Greece, but his resolution was adopted before he heard of Lord Byron’s intention to join the Greeks’. And, as Finlay adds, ‘…In November he [Finlay] reached Cephalonia having been 45 days in passage from Venice to Zante where he was candidly received by Lord Byron and Sir Charles Napier.’ A few days later he passed on to the Peloponnese.

What are we to make of all this? In trying to understand why someone like Finlay joined the Greek Revolution we need to take into account social and economic conditions, but also intellectual motivations. If Finlay had followed a career in the army or in commerce, his choices would probably have been different. Having only ‘yearly fortunes’, Kirkman as a mentor and a liberal legal education played a big role in his decision to come to Greece. Well, maybe not in his actual coming, but in his inclination to come. Because, notwithstanding what Finlay wrote, as was the case with many British Philhellenes, it would be Lord Byron’s involvement in the Greek Revolution that would transform words and wishes into action.

And as for what happened to Finlay once he came to Greece…well that’s for the next story…and with stories of this kind, this was just the beginning….

Dr Michalis Sotiropoulos

The 1821 Fellow in Modern Greek Studies

British School at Athens

For more information on this BSA research project, visit the dedicated webpage, Unpublished Archives of British Philhellenism.

[1] But published in 1822 in Percy Shelley, Hellas: A lyrical drama (London: C. and J. Ollier, 1822).

[2] Douglas Dakin, British and American philhellenes during the war of Greek Independence, 1821-1833 (Etaireia Makedonikon Spoudon: Thessaloniki, 1955), p. 36.

[3] B.4 (9) – [The Finlay Papers: A Catalogue, compiled by J.M. Hussey (BSA/Thames & Hudson: Oxford, 1973), p. 70, available also online at https://www.jstor.org/stable/40855968.]