O! Sycophant!

Who are we talking to when we write in our books? George Finlay’s books are stuffed with letters from friends and endearingly tart marginalia. For the last few weeks I’ve been cataloguing these letters and notes for future researchers and have been thinking about what they can tell us about Finlay, his social circle, and life in nineteenth-century Athens.

Young Finlay practises his signature in pencil in his Bible, BSA Library, Fin. Q 1.19

SCARCE BOOKS AND A FEROCIOUS BOOK GUARDIAN

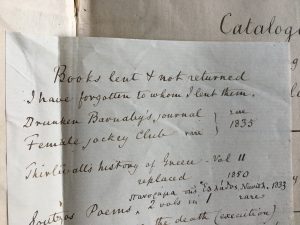

English books were scarce in Athens for most of the nineteenth century, and an eager reader had to use their social connections to get hold of what there was. Fortunately for Finlay, he had an unusually large library, but tucked into his volumes are reams of letters from less well-equipped acquaintances asking the loan of a book. ‘I know you have refused ambassadors,’ says one, ‘but if I could just borrow the book for two days…” Finlay’s rueful list of ‘Books lent and not returned and I have forgotten to whom I lent them’ shows he could be – when he felt like it – a generous lender – but his list also demonstrates the value he gave to his missing books, many of which must have been hard to replace (Is this all it shows?).

‘Books lent and not returned. I have forgotten to whom I lent them,’ BSA Archive, FIN/GF/A/35

Books from George Finlay’s personal library now part of the BSA Library

SHARED READING

Reading today is generally understood as a private act. This was not always the case; it certainly wasn’t in Finlay’s Athens. With books scarce, an eager reader had to use social contacts to satisfy their literary appetite, making reading a more communal practice. Being well-read in this context had a certain cachet of its own, suggesting a strong social network available to the reader. In this context, the experience of reading becomes a gift from book owner to book reader, strengthening social ties. Readers are also more likely to discuss their opinions of books that are shared. The nineteenth-century habit of reading aloud would have drawn an entire household into a text – and they could discuss it together afterwards.

At a time when books were imbued with social significance, the gift of a book could carry sentimental weight. We can see Miss Lenormant’s note to Finlay pasted into her father’s published commentary on Plato, offering the book in memory of him.

MARGINALIA

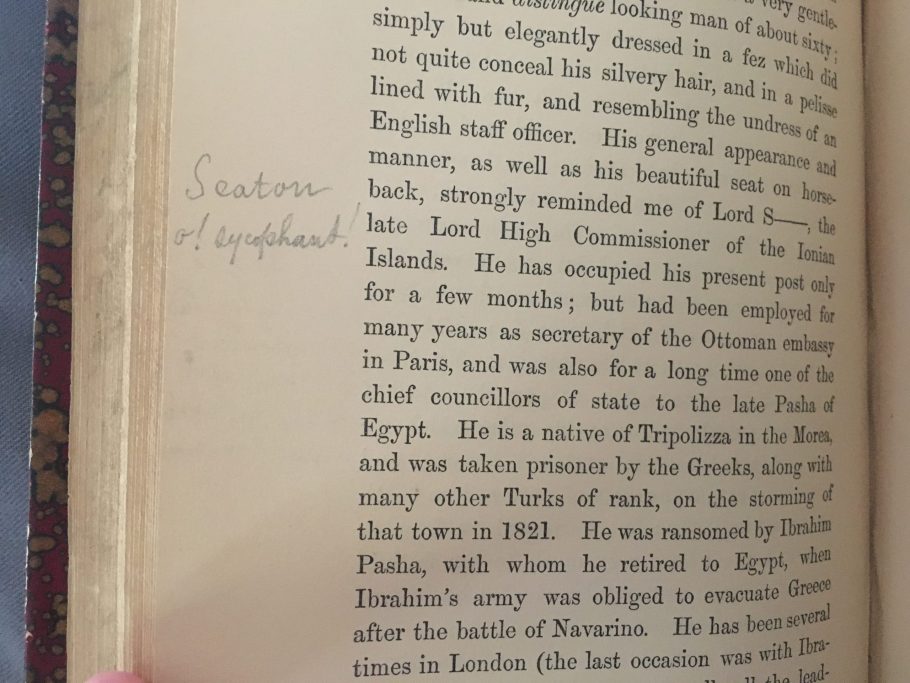

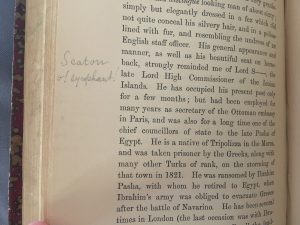

Given the number of hands Finlay’s books passed through, the acidic comments that decorate the margins of each book can be surprising. Finlay’s neat handwriting chides authorial inadequacy (‘o! sycophant!’), the incompetence of historical figures (Alexandros Mavrocordatos is ‘not much of brave and even less of a soldier’) and even so-called friends (‘no’ next to Charles Tuckerman’s description of him as ‘my friend’). Having checked my own marginalia for blunders before lending a book, I know too well how this ostensibly private act can also be a way of self-presentation. So why did Finlay write his notes and paste in those letters, and what audience did he have in mind for them?

‘O! Sycophant!’, BSA Library, P 4.3

‘Not much of brave and even less of a soldier’, BSA Library, Fin. D 112

AUDIENCES

The letters could be a form of name-dropping (‘Look! I know John Stuart Mill!’), an extension of his habit of carefully grouping together similar records (a letter from Professor John Stuart Blackie can be found tucked into a book authored by the same), or simply for the pleasure of blowing off steam (‘Americans!’ next to a description of U.S. foreign policy). Sometimes, he seems to enjoy playing the role of the grumpy old man to himself and to his friends. At others, he uses his first-hand experience of Greek history to enrich the historical record for posterity. Marginalia also often seems to be used as a tool to digest a text and formulate his own opinions on the subject.

BSA Library, Fin. D 113

Marginalia can also be used to restrict the liberty of readers, prodding them into the ‘proper’ way to read a text. How would this have affected Finlay’s friends’ readings of his books? I’d have enjoyed watching their faces as they encountered the marginalia. Would they have shown disagreement or agreement? Surprise or amusement? Distaste or admiration?

If only they’d left marginalia of their own.

Felicity Crowe

The 1821 Archive Project Assistant

British School at Athens

Further Reading:

If you’d like to find out more about how people read in the past, you might enjoy the Reading Experience database compiled by the Open University: http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/index.php

For more information on this BSA research project and to see more 1821 Archive Stories, visit the dedicated webpage, Unpublished Archives of British Philhellenism.