Ad Familiares: Christopher Stray’s correspondence with Patrick Leigh Fermor

Chris Stray is known to all Classicists as someone who poses the pertinent questions.

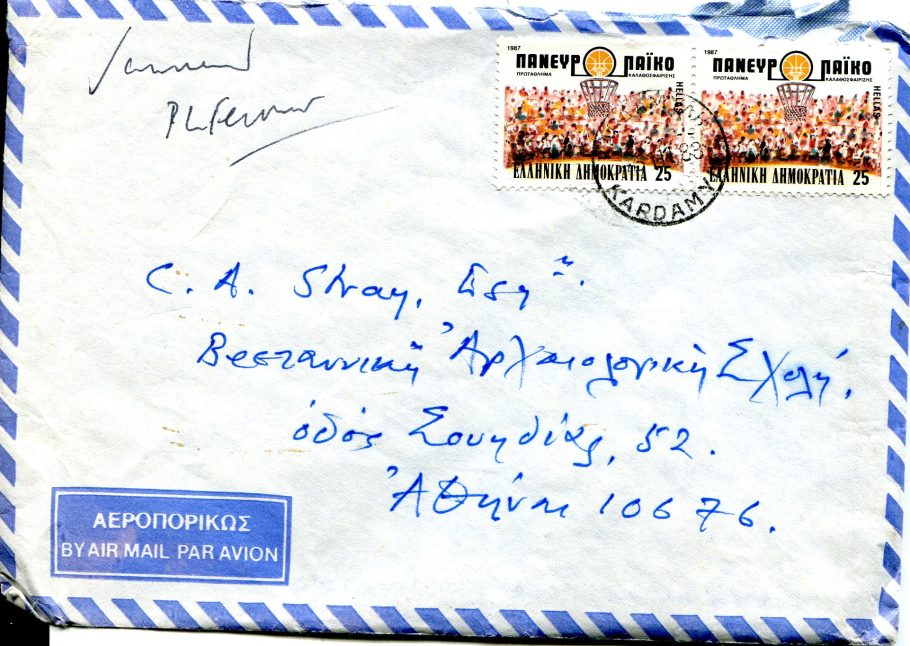

In 1988, while staying at the BSA and studying how European monoglot travellers used Latin to communicate, Stray wrote to Patrick Leigh Fermor, the celebrated travel writer who had a house at Kardamyli in the southern Peloponnese, with a particularly good enquiry. It related to what was the most famous episode in Leigh Fermor’s eventful life. In 1944, in an operation led by Leigh Fermor, SOE and the Cretan resistance had staged an audacious kidnap of a German general, Heinrich Kreipe, and after a perilous trek over the mountains with German forces in hot pursuit, had spirited him away by motor launch to Egypt.

In A Time of Gifts (1977), the first instalment of Leigh Fermor’s account of his walk from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul in 1933-35, he describes how the tension between Kreipe and himself was eased when his German captive, gazing at the crest of Mt. Ida at dawn, started to recite Horace’s Soracte Ode (Ad Thaliarchum, 1.9), vides ut alta stet nive candidum/ Soracte, “You see how Soracte stands bright white in deep snow.” Knowing the poem by heart, Leigh Fermor recited the remainder of it, and “things were different between us for the rest of our time together”, common ground established between enemies.

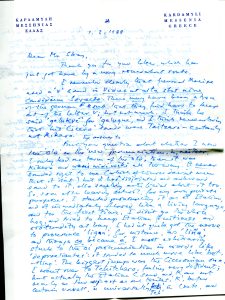

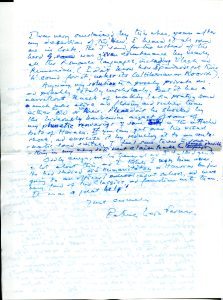

Stray’s question for Leigh Fermor was how he and Kreipe had pronounced the Latin that they exchanged that day; and somewhat to his surprise a long letter, with a very full report and extended quotation from Horace’s Odes, presently arrived back at the British School.

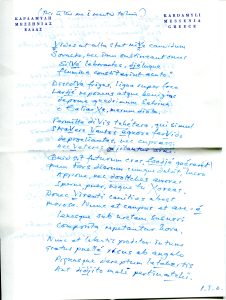

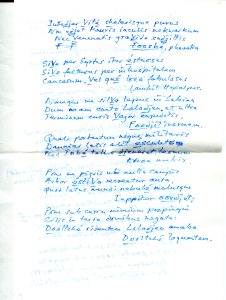

Leigh Fermor’s account of this episode in A Time of Gifts comes in the context of a list of the poetry he had learned by heart, and which he would recite aloud as he walked through Europe. “Passages, uttered with gestures and sometimes quite loud, provoked, if one was caught in the act, stares of alarm.” In his letter to Stray his explanation of his principles of pronunciation is illustrated with a collection of odes, or selections therefrom, presented phonetically, and (I think we can assume) written down from memory: he remarks in A Time of Gifts that texts committed to memory before his age in 1933, eighteen, had proved to be there more or less for good, and two of the poems quoted in his letter are familiar from that earlier account: the Soracte Ode (“this is the one I recited to him”, he comments in the letter) and the conclusion of the Regulus Ode (3.5), which was one of his favourites on the road, though less embarrassing when caught in full flow, he informs us, than Henry V’s speech at Harfleur. The other poems he sets out for Stray are some of Horace’s most familiar—he was candid in A Time of Gifts that the larger list of memorised texts was “all too revealing … of a particular kind of growing up”, that is, a public-school education: Integer vitae (1.22, which I also have by heart), Diffugere nives (4.7, Housman’s favourite poem), and 3.29, in the humble opinion of your blogger the very finest Latin poem of the lot.

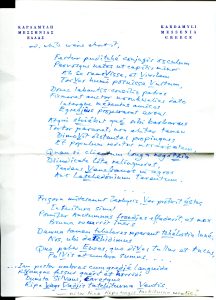

Leigh Fermor’s recollection is that Kreipe pronounced Latin consonantal “u” as (English) “v”, perhaps tending slightly to “f” under influence of German: geluque came out as “gelukve”, and when Cicero cropped up in their ongoing conversations, he was “Tzitzero”. Kreipe, who was 48 at the time of his abduction (Leigh Fermor was still in his twenties), was the thirteenth child of a Lutheran pastor in Hanover, and had had an education steeped in Classics before attending an officers’ cadet school. His pronunciation of Latin is thus a representative, traditional German style.

Leigh Fermor’s own pronunciation, which he proceeds to elaborate to Stray, is altogether less orthodox, which is the least we should expect. To Stray’s enquiry whether he used the Old or the New pronunciation of Latin (“all latin masters hav one joke”, in the words of Molesworth, and the Old is what makes “Caesar adsum jam forte” funny; there is a more authoritative discussion in C.A. Stray, Classics Transformed, Schools, Universities, and Society in England, 1830-1960, Oxford 1998), he replies that the New was what he had been taught (“I only had one term of the ‘Old’, then it was Kikero and weni, widi, wiki all the way”). But the New pronunciation (an attempt to approximate the original pronunciation of Cicero, Virgil and Horace) “never sounded right to me … it had a disjointed and awkward sound to it, also something artificial about it too.” His own method was to adopt a broadly Italian pronunciation, while trying “to keep Italian fruitiness and orotundity at bay”, an approach to which he attributes “a marvellous knack of making Latin poetry sound more alive and flowing and richer than either the Old or the New.”

In an effort to restage this encounter in blog form, necessarily hopeless, here is the concluding section of 3.5, the Regulus Ode, as Leigh Fermor presents it for Stray. The plain Latin text is followed by a translation (indebted to David West), Leigh Fermor’s phonetic rendering (slightly corrected: he hasn’t remembered it perfectly on this occasion!), and a notional German version. We learn elsewhere that he and Kreipe reconstructed this famous coda between them (a peculiarly apt one, given Kreipe’s imminent transfer across the Mediterranean to British custody in N. Africa), and Leigh Fermor tells Stray that their differences in pronunciation were a regular topic of discussion between the two: “I think I won him over.”

atqui sciebat quae sibi barbarus

tortor pararet; non aliter tamen 50

dimouit obstantis propinquos

et populum reditus morantem

quam si clientum longa negotia

diiudicata lite relinqueret,

tendens Venafranos in agros 55

aut Lacedaemonium Tarentum.

And yet he knew what the barbarian

torturer had in store for him; all the same

he parted the kinsmen blocking his path

and the Roman people delaying his return

just as if, when a case had been decided,

he were departing, after extended efforts

on his dependants’ behalf, for the Venafran fields

or for Tarentum, founded from Sparta.

atqui shiebat que sibi barbarus PLF

tortor pararet; non aliter tamen 50

dimovit obstantis propinquos

et populum reditus morantem

quam si clientum longa negotia

diiudicata lite relinqueret,

tendens Venafranos in agros 55

aut Latchedemonium Tarentum.

atkvi stziebat kve zibi barbarus HK

tortor pararet; non aliter tamen 50

dimovit obstantis propinkvos

et populum reditus morantem

kvam zi clientum longa negotzia

diiudicata lite relinkveret,

tendens Venafranos in agros 55

aut Latzedemonium Tarentum.

In Classics Transformed Stray discusses not only the means of communication that Latin offered monoglot travellers, but also the obstacle to communication represented by the national variations in pronunciation. But let us leave Leigh Fermor and Kreipe trading shiebats and stziebats as German forces scour the mountains for them. As for Leigh Fermor’s rejection of reconstructed ancient Latin pronunciation, he allows in his letter that “my solution is a purely private one, and no doubt probably unscholarly.” There are indeed good scholarly reasons to prefer yam to jam and Kikero to either Tchitchero or Tzitzero. We can decide for ourselves whether his version of Odes 3.29.24, ripa uagis taciturna uentis (“the river bank silent [and with no] stray breezes”), “Ripa vadjis tatchiturna ventis”, is, as he insists, “nicer than ‘Ripa wagis tackiturna wentis’”.

The appeal of Horace’s individual odes as targets for memorisation is an element of this story. The poems are short, their expression a miracle of concision, and the mosaic of verbal agreements that frustrates students is a help, not a hindrance, if one is piecing it back together in one’s head. But Horace also had a habit of accompanying travellers in more concrete form. Leigh Fermor had left England with “the Loeb Horace, Vol. I”, a gift from his mother; but when he lost his rucksack in Munich it was the kindness of Baron Reinhard von Liphart-Ratshoff, an emigré from Estonia, who, as Leigh Fermor was setting out, “put a small duodecimo volume in my hand … beautifully printed on thin paper in Amsterdam in the middle of the seventeenth century, bound in hard green leather with gilt lettering.” Like the first volume of the Loeb this exquisite book (actually published in 1699) contained Horace’s Odes and Epodes, but most unlike the Loeb were its mezzotints of “the Forum and the Capitol and imaginary Sabine landscapes; Tibur, Lucretilis, the Bandusian spring, Soracte, Venusia.”

As a traveller with Horace in his pocket, Leigh Fermor was in a venerable tradition. Coleridge called Horace “the man whose works have been in all ages deemed the model of good sense, and are still the pocket companions of those who pride themselves on uniting the scholar with the gentleman.” To male, educated British, Germans and other nationalities Horace, always read selectively (the Odes much more than the Epodes, for instance), represented a gentlemanly ideal; when abroad, an anchor for their identity.

On a mountainside in Crete men of very different backgrounds, not to mention pronunciations of Latin, came together and discovered what they had in common: “We had both drunk at the same fountains”, comments Leigh Fermor in A Time of Gifts. But there is something deeply appropriate in the Odes being the catalyst for this rapprochement between enemies. Horace’s lyric poetry is haunted by the Civil Wars, the violent divisions between members of the Roman elite that its poems of drinking and friendship work to overcome. A Time of Gifts is haunted, conversely, by the future of the Europe that the young Leigh Fermor traverses. Within a very few years he would be fighting the country in which he had encountered such kindness.

Patrick Leigh Fermor’s letter to Chris Stray is safely preserved in the archive of the BSA.

Llewelyn Morgan

Brasenose College, Oxford