Magoula Hunting or The Romance of Excavation

In the summer of 2020, ‘Digital Mycenae’ went live, digitally reuniting the Mycenae excavation archives held at the Faculty of Classics Cambridge and the British School at Athens. Based on this project’s success, we began to formulate a plan for ‘Digital Thessaly’. This was designed to be a collaborative project with the BSA and two archives in Cambridge: in the Faculty of Classics and Pembroke College. Part one of our plan, with substantial input from the archivists at the three institutions, has come to fruition in Early Civilisation in Northern Greece on BSA Digital Collections, facilitated by the BSA IT Officer. A number of the research notebooks kept by Alan Wace that formed the basis of his and Maurice Thompson’s Prehistoric Thessaly, published in 1912, are now available. Wace is an important link between Athens and Cambridge, as a former Director of the BSA (1914–1923) and as Laurence Professor of Classical Archaeology at Cambridge and Fellow of Pembroke College (1934–1944).

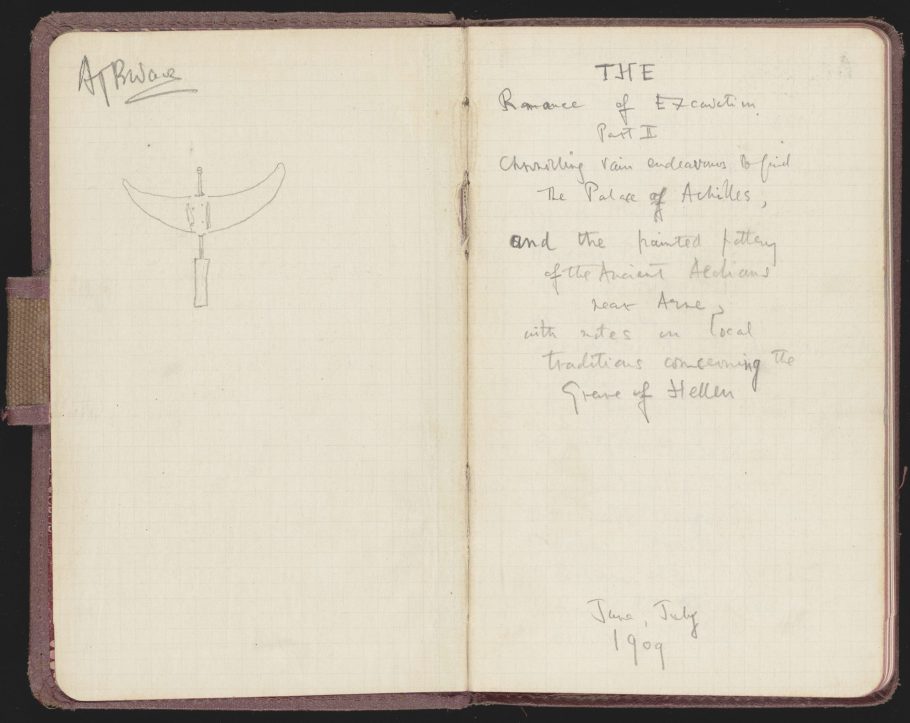

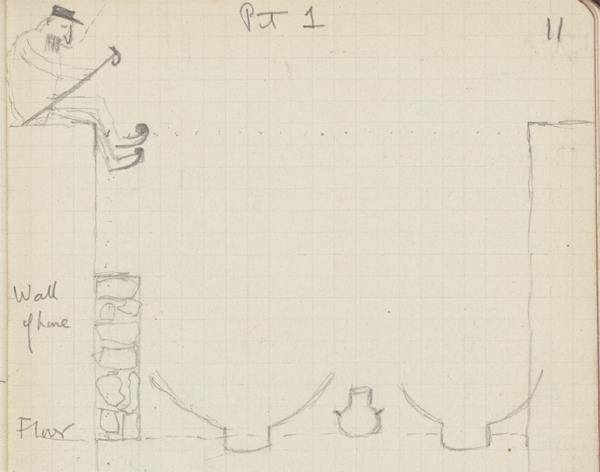

The BSA Archive holds five excavation notebooks that cover seven different sites excavated between 1907 and 1912 in Thessaly and the Spercheios valley near Lamia (Fthiotida). In addition, the BSA SPHS Image collection contains photographs originally donated to the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies (SPHS) by Wace that relate to this project. The Cambridge holdings are more extensive. For the first phase of our project, three notebooks were chosen and comprise Wace’s The Romance of Excavation chronicles: parts I and II (Pembroke College), and part III (Faculty of Classics). Although Wace is rightly known for his more serious academic publications, these notebooks give a rare glimpse into his character and the sheer delight he must have felt in discovering Greece’s past. The Romance of Excavation notebooks appear to be Wace’s own field diaries with droll subtitles. Similarly, another Cambridge Classics notebook (GBR/3437/AJBW/1/18*) clearly demonstrates Wace’s whimsical side, bearing the tongue-in-cheek subtitle ‘Reumatic Adventures in Search of Antiquities by Lord Rufford of Tooting accompanied by his faithful dragoman Cassius’! The three parts of The Romance of Excavation (1908-1910) contain various notes (details of the excavations, sites and museums visited, Greek grammar notes, photograph logs, workman’s schedules, expenses, copied inscriptions, etc.) and sketches, a few of which show amusing details such as the one below. They complement the BSA excavation notebooks, providing more information on the various excavations as well as descriptions of Wace’s wider interests and explorations.

The Papers of Alan J. B. Wace, GBR/1058/WAC. Pembroke College Library: The Romance of Archaeology II, detail of pit 1 from Paleomylos (Lianokladi).

The subtitles of The Romance of Excavation notebooks provide us with a clue as to Wace’s expectations, even if phrased in a humorous erudite manner. The first begins with ‘Account of Certain Unfruitful Endeavours to find the site of the city of ITONOS or failing that the rich prehistoric city of Phthiotis’. Itonos was listed in Homer’s Catalogue of Ships (Iliad 2) as an ancient city in Phthiotis – thought in antiquity to be the general area of southern Thessaly and the Spercheios valley. The second notebook’s subtitle is equally grand: ‘Chronicling vain endeavours to find The Palace of Achilles, and the painted pottery of the Ancient Aeolians near Arne, with notes on local traditions concerning the Grave of Hellen’. The area of southern Thessaly and the Spercheios valley was traditionally the homeland, not only of Achilles, but also the ‘race’ of Ancient Aeolians who were speakers of the Aeolic dialect. The Aeolian city of Arne was thought to have been built over and later called Cierium (Kierion), a known site located near the villages of Sophades and Mataranga, southeast of Karditsa. Lastly, Hellen – not to be confused with Helen of Troy – was the eponymous ancestor of the Hellenes which the Homeric Catalogue of Ships indicates were a small tribe in Thessalic Phthia commanded by Achilles. It is also significant that Wace later mentions in Prehistoric Thessaly that the Spercheios river was, even in the early 20th century, sometimes referred to locally as the Hellen river. The first two notebooks have Homeric connotations. The last notebook, however, seems resigned to the fact that their lofty expectations of uncovering a Bronze Age ‘Homeric’ civilisation akin to those identified in southern Greece would not be realised: ‘Detailing some futile endeavours to make great discoveries in Thessaly’. What they did discover, however, added significantly to the understanding of an earlier prehistory in the north which was little known at the time.

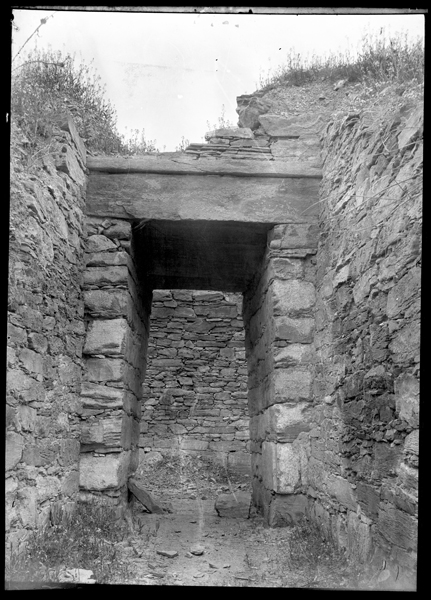

Wace’s Thessaly research began in the wake of Christos Tsountas’ discoveries at the Neolithic sites of Dimini and Sesklo near Volos. In April 1905, prior to any excavation, Wace made an exploratory study tour to the Volos area, possibly visiting Dimini. He also explored the Pelion peninsula and the islands of Skiathos and Skopelos. Wace was hoping to identify promising sites to investigate. He eventually set his sights on a place called Theotokou in southeast Pelion, identified as the possible ancient Greek city of Sepias. Wace returned with J.P. Droop to excavate Theotokou in 1907; it proved to contain some ‘Hellenic’ walls and early Geometric burials near a ruined Byzantine church.

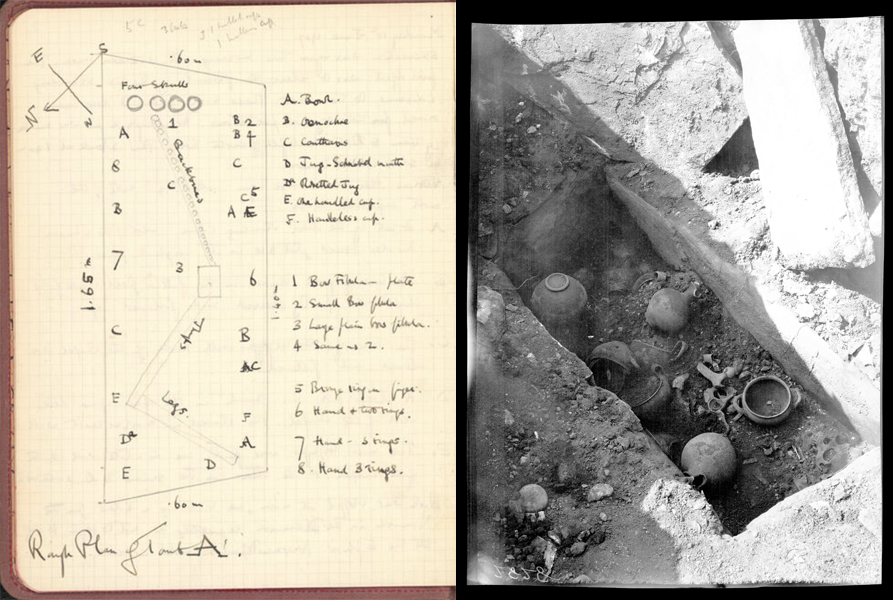

Left: THES/1/1*: Page from ‘Thessaly’ Notebook. Right: BSA SPHS 01/1011.2828. Theotokou, Tomb A and grave contents

The BSA Annual Report for 1907/1908 indicated that there was a ‘need for a determined effort to throw more light on the chronology of the early civilisation of Northern Greece and on its relationship to other cultures’. Wace returned to Thessaly with Droop and another BSA scholar, Maurice Thompson, to excavate a magoula, or prehistoric mound, identified at Zerelia, also thought to be the location of Itonos. At Zerelia they were expecting to discover the famed temple of Athena Itonia sitting on top of accumulated deposits of earlier remains since they ‘recognised that the mound was probably formed by the accumulation of débris from prehistoric settlements’. Instead, they discovered eight successive settlements of ‘Prehellenic’ remains dating back to the Neolithic with some ‘Hellenic’ material in the top layer, but no evidence of the temple.

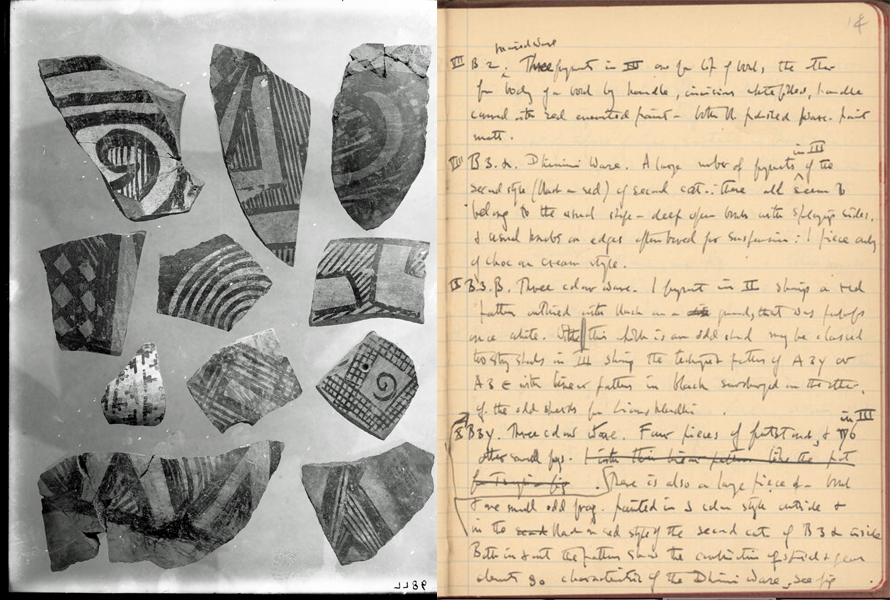

After Zerelia, Wace and Thompson returned (Droop having dropped out due to ill health) to excavate four other magoules in two years: Lianokladi (in the Spercheios valley) and Tzani (near the location of Arne/Ciericum) in 1909, and Rakhmani (north of Larisa) and Tsangli (south of Larisa) in 1910. In order to sort out the chronology, particular interest was devoted to devising pottery sequences – based on initial work done by Tsountas. The basis of this work was a detailed study of the typology and distribution of hundreds and thousands of pottery sherds, carefully examined both on-site and back in Athens (cf. Loy 2022, n. 17). It wasn’t until 1910, however, that their sequencing came together. In the 1910 excavation notebook (THES/1/4), they were beginning to work out the pottery descriptions that would ultimately be published as Chapter 2 of Prehistoric Thessaly. Pottery categories Α1 to Α6 were defined as First Neolithic while Β1 to Β3 were Second Neolithic. Groups Γ1 and Γ2 were Chalcolithic while the Bronze Age was assigned to Γ3. Early Geometric was assigned the categories Δ1 and Δ2. Each category was sub-divided by specific styles – such as incised ware, monochrome red, red-on-white, black polished – identified by a lower-case Greek letter following the category. They also began to develop typologies for the stone tools, figurines and other objects based on this chronology. Critical for developing this chronology was a study-visit to the Volos Museum collection in the second half of 1909. Detailed observational and bibliographic notes kept by Wace from this visit are contained in another of the Cambridge Classics notebooks (GBR/3437/AJBW/1/16*), along with a rough-draft text that would eventually become the introduction to Prehistoric Thessaly.

Left: BSA SPHS 01/2972.7786. Rachmani II sherds (B3α). Right: THES/1/4 Page from Rachmani Notebook with descriptions of B2 and B3α to B3γ pottery.

Wace and Thompson’s investigations were not restricted to the excavation of these five magoules. In a postscript to an article published in volume 1 of the University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, Wace, Droop and Thompson describe their search late in 1908 for similar sites in outlying areas in Elis (near Olympia) and Aetolia in Western Greece, but they found no evidence of magoules. Thereafter, much of the magoula hunting was in Thessaly and the Spercheios valley. During the years they were excavating, Wace and Thompson made forays into the surrounding countryside to identify and understand the distribution of magoules. The BSA’s Annual Reports mention there was an intensification of magoula hunting in 1909 and again in 1910. Photographs from these expeditions come from an album in the Cambridge Classics collection (GBR/3437/AJBW/3/20*), while rough notes and initial observations were recorded in a notebook from the Pembroke collection (GBR/1058/WAC/1/5*).

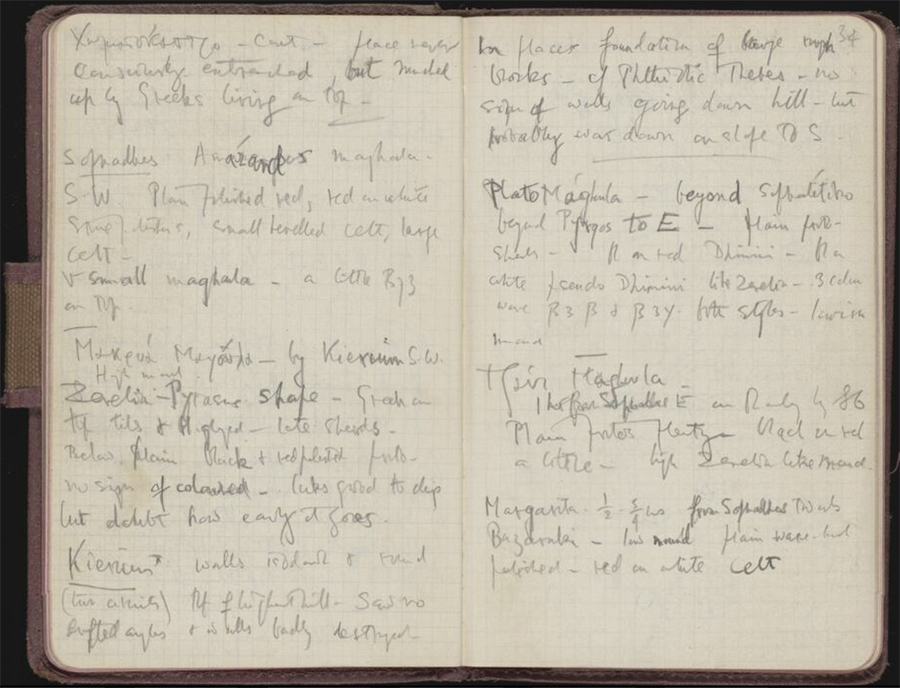

In his 1915 book on practical aspects of excavation, Droop lists magoula hunting as a research method, described as an ‘excellent although weary sport’ in search of magoules (defined as ‘gentle swelling mounds left by the débris of prehistoric settlements’) usually with the aid of local knowledge. Prehistoric Thessaly, the final publication of their Thessaly investigations, provides descriptive locations of 124 sites, extending the list begun by Tsountas. Their visits to many of these sites are also described in the The Romance of Excavation notebooks – including Ciericum and site numbers 50 (Khomatokastro) and 52 (Platomaghula) listed on the page shown below.

The Papers of Alan J. B. Wace, GBR/1058/WAC. Pembroke College Library: The Romance of Archaeology II, pages describing mounds in the Sophades area.

Just before the publication of Prehistoric Thessaly in 1912, Wace and Thompson delivered a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society on ‘The Distribution of Prehistoric Sites in Thessaly’. The main argument stated that there was a difference between the west and east of the Pindus mountain range, borne out by their abortive search for mounds during their exploration of Western Greece in 1908. Secondly, they indicated that there were routes from Thessaly to the north and to the south, making it likely that cultural influences travelled along those lines. A thread in the discussion that followed the talk made references to similar materials found in the Central Europe and Anatolia. An article by Wace, Thompson and T.E. Peet (who worked with them in 1908) debunked the idea that similar material found in wide-spread areas equated cultural connections. Their article, published in Classical Review, made the argument that many connections between Central Europe, the Balkans and the Aegean area were often made by superficial similarities in ‘decorative types’ and are not true connections. Rather, they were inclined to subscribe to the theory that similarities were a result of independent and parallel developments by different tribes of the same ‘race’.

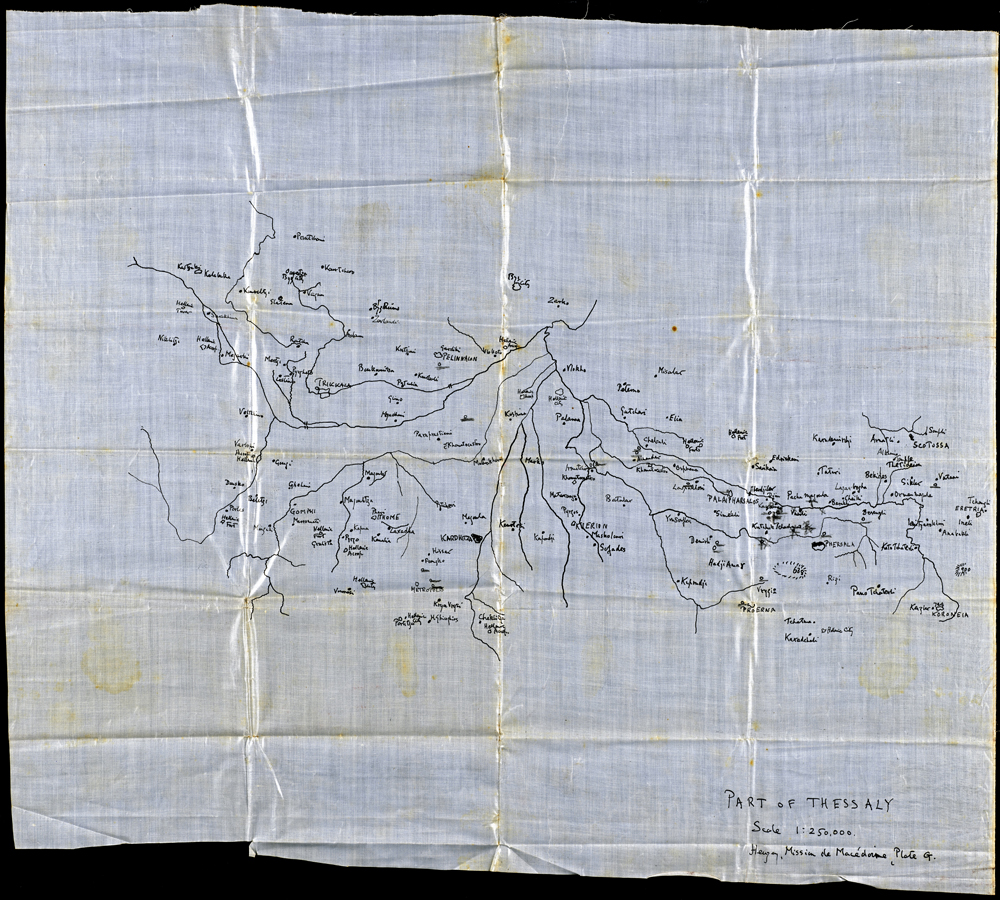

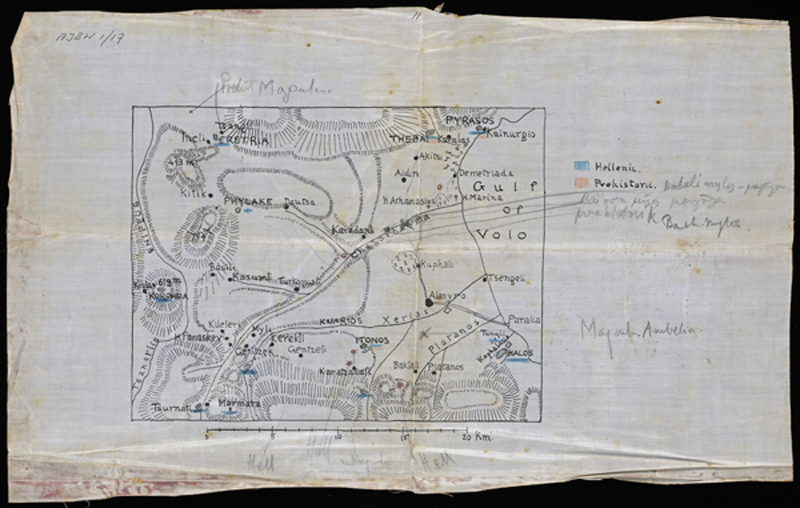

Another point raised in the discussion following their Geographical Society lecture came from D.G. Hogarth on the lack of systematic mapping of sites. Indeed there are no comprehensive maps, other than general topographical maps, in Wace and Thompson’s publications showing the spatial distribution of sites. Yet, Wace possessed several detailed maps. One of the maps is entitled ‘Part of Thessaly’, hand-drawn on fine linen that shows evidence of folding and staining. This map was reproduced from Carte d’une partie de la Thessalie (Plan G) in the 1876 Mission archéologique de Macédoine by Léon Alexandre Heuzey who located ancient sites and plotted possible ‘tumuli’ marked with asterisks. The other map is similarly on linen and shows the area west the Gulf of Volos. Wace’s traced copies may have been his field maps, easily folded and tucked into a pocket, used to locate and confirm the presence of magoules on the ground. They, however, were never translated into a spatial representation of the 124 sites described in Prehistoric Thessaly.

The Papers of Alan J. B. Wace, GBR/1058/WAC. Pembroke College Library: The Romance of Archaeology II (loose papers), Sketch map: ‘Part of Thessaly’.

Alan J. B. Wace Archive, Faculty of Classics Archives, University of Cambridge. GBR/3437/AJBW/1/17. The Romance of Archaeology III (loose papers), Sketch map of the area west of the Gulf of Volos.

Later BSA scholars took up the search for prehistoric sites in Thessaly, using Wace and Thompson as a starting point. Alan Hunter, for his Oxford BLitt thesis in 1953, attempted to map some of the Wace and Thompson sites, particularly those which contained Bronze Age material. David French (who married Wace’s daughter, Lisa), in the 1960s and 1970s re-explored the area and mapped many of the Wace and Thompson sites in addition to adding more mounds to the numbering sequence. French’s numbering system was used, in turn, by Paul Halstead for his PhD research in the 1980s. More recently, a research project called IGEAN: Innovative Geophysical Approaches for the Study of Early Agricultural Villages of Neolithic Thessaly has produced a digital map of sites – identified by ground truthing – which references the Wace and Thompson site numbers and the succeeding French/Halstead numbers as well as data from numerous Greek scholars – particularly Kostas Gallis – who have surveyed the area. The project was organised by the Laboratory of Geophysical – Satellite Remote Sensing and Archaeo-environment at the Institute for Mediterranean Studies (University of Crete) in cooperation with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Magnesia. Another recent project in Western Thessaly employed remote sensing coupled with ground truthing to reveal a hitherto unsuspected wealth of prehistoric settlements and connecting paths. Despite the radical modern levelling of the landscape for agricultural improvement, this technique allowed the project to detect an earlier landscape – one that would have been more familiar to Wace and Thompson (see Orengo et al. 2015). Prehistoric Thessaly has now become one of the most comprehensively studied and mapped archaeological areas of Greece. No doubt, Wace and Thompson (and certainly Hogarth) would approve.

Phase two of this project will be completed in the next academic year (2022–2023) and will digitise the remaining notebooks dealing with Wace and Thompson’s research in Northern Greece. This includes their visits, beyond the borders of Greece at that time, to Macedonia (1909-1910). These visits north were, in part, to discover the extent of the spread of ‘Thessalian’ cultural material in prehistoric northern mounds – toumbes, as they are called locally. On one trip north, Wace and Thompson travelled with a group of migratory Vlachs from Samarina prompting a detour into ethnography and resulted in their book, Nomads of the Balkans (1914) – but that is another story.

* Indicates material not yet digitised and scheduled for phase two of the project.

Deborah Harlan

Archival Researcher

British School at Athens

Michael Loy

Assistant Director

British School at Athens

Notebooks (Early Civilisation in Northern Greece) and Images (BSA-SPHS Image Collection) are available on the BSA’s Digital Collections page.

Click here for more BSA Archive Stories.

Further Reading

Droop, J.P. 1915. Archaeological Excavation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

French, D.H. 1972. Notes on prehistoric pottery groups from central Greece. Athens (privately printed).

Halstead, P. 1984. Strategies for Survival: An Ecological Approach to Social and Economic Change in Early Farming Communities in Thessaly, N. Greece. Ph.D. Thesis, Cambridge University.

Hunter, A. 1953. The Bronze Age in Thessaly and its environs with special reference to Mycenaean culture. B.Litt, Oxford University.

Loy, M. 2022 (forthcoming). ‘A brief history of the BSA Museum Study Collection’, Archaeological Reports 68.

Orengo, H.A., A. Krahtopoulou, A. Garcia-Molsosa, K. Palaiochoritis and A. Stamati 2015. ‘Photogrammetric re-discovery of the hidden long-term landscapes of western Thessaly, central Greece’, Journal of Archaeological Science 64: 100-109.

Peet, T.E., Wace, A.J.B. and Thompson, M.S. 1908. ‘The Connection of the Aegaean Civilization with Central Europe’, Classical Review, 22(8): 233–238.

Τσούντας, Χρήστος, 1908. Αι προϊστορικαί ακροπόλεις Διμηνίου και Σέσκλου. Athens: Σακελλαρίου Π.Δ.

Wace, A. J. B. 1913-1914. ‘The Mounds of Macedonia’, Annual of the British School at Athens, 20: 123–132.

Wace, A.J.B. and Droop, J.P. 1906. ‘Excavations at Theotokou, Thessaly’, <emAnnual of the British School at Athens, 13: 309–327.

Wace, A. J. B., Droop, J. P. and Thompson, M. S. 1907-1908. ‘Excavations at Zerelia, Thessaly’, Annual of the British School at Athens, 14: 197–225.

Wace, A. J. B., Droop, J. P. and Thompson, M. S. 1908. ‘Early Civilization in Northern Greece’, University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, 1: 118–130.

Wace, A.J.B. and Thompson, M.S. 1909. ‘Early Civilization in North Greece: Preliminary Report on Excavations in 1909’, University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2: 149–158.

Wace, A.J.B. and Thompson, M.S. 1909. ‘Prehistoric Mounds in Macedonia’, University of Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2:159–164.

Wace, A. J. B. and Thompson, M. S. 1911. ‘The Distribution of Early Civilization in Northern Greece’, The Geographical Journal, 37(6): 631–636. Followed by: ‘The Distribution of Early Civilization in Northern Greece: Discussion’ 37(6): 636–642.

Wace, A. J. B. and Thompson, M. S. 1912. Prehistoric Thessaly: being some account of recent excavations and explorations in North-eastern Greece from Lake Kopias to the borders of Macedonia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wace, A.J.B. and Thompson, M.S. 1914. The nomads of the Balkans: an account of life and customs among the Vlachs of northern Pindus. London: Methuen.