An Idea is Born: ‘The Mini-Lab’

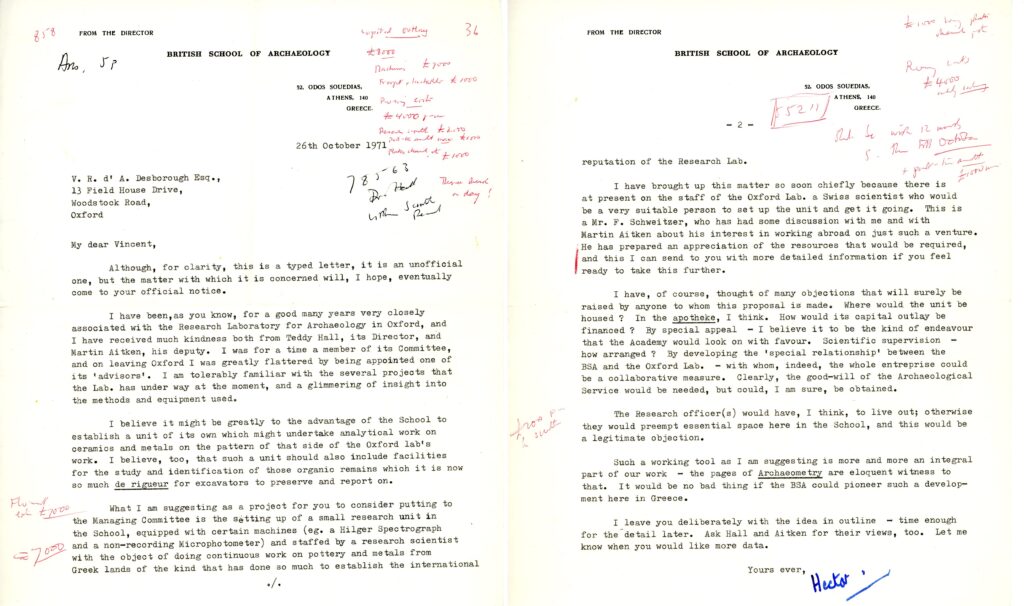

A letter from Hector Catling to Vincent Desborough, on 26th December 1971, first proposing the establishment of a laboratory for archaeological science at the BSA (BSA Corporate Records, London, Fitch Lab box 2)

The Marc and Ismene Fitch Laboratory for archaeological sciences was established in 1974. Its history however, reaches further back with the seeds of its creation sown in Oxford in the early 1960s (Kiriatzi 2022; Catling 2005). The then Director of the BSA, Sinclair Hood, approached a number of individuals at Oxford to investigate the potential for using scientific techniques to investigate the provenance of Mycenaean and Minoan pottery—and without realising, Hood had brought together a team of individuals, Hector Catling[1], Edward ‘Teddy’ Hall[2] and Martin Aitken[3], that would eventually lead to the founding of the Fitch Laboratory at The British School at Athens.

Throughout the 1960s, this team worked together, often with Teddy and Martin in the background, to investigate the provenance of Minoan and Mycenaean pottery, as evidenced by a series of publications in both Archaeometry and the Annual of the British School at Athens (Catling 1963; Catling et al. 1963; Catling and Millet 1965a, 1965b). This project aimed to begin exploring the production and distribution of pottery across Greece and to test whether elemental analysis was able to distinguish pottery produced on Crete and mainland Greece. A second project that was initiated a little later, and continued at the Fitch laboratory once it was founded, was that on Inscribed Stirrup Jars. This project aimed to use scientific techniques to explore the provenance of these Jars and in turn contributing to scholarship on Linear B (Catling and Millett 1965c, Catling and Jones 1977; Catling et al. 1980).

These projects and collaborations clearly created a spark in both Hector Catling and in the field of archaeology. Suddenly questions about where pottery came from could be investigated in new ways. In fact, in a previous blog post in the BSA Archive Stories there is further evidence for this. Annie Ure, a pre-eminent expert of Boeotian archaeology, and Hector are in correspondence in 1966 about possible analysis of Annie’s ‘Euboean pottery’, indicating that archaeologists were seeking out scientists to analyse their material.

The proposal for a ‘Mini-Lab’

It appears that some of the most important discussions between Hector, Teddy and Martin happened within the dining halls of the Oxford Colleges. Infact, it was at such a meal at Linacre College where the suggestion of setting up a laboratory within the grounds of the BSA was first proposed by Martin Aitken to, the then Director Elect of the BSA, Hector Catling (Catling 2005). It seems that Hector liked this idea, and as soon as his Directorship began in October 1971, he got to work on making it a reality!

In a letter to Vincent Desborough[4] as the chairman of the BSA Managing Committee, on 26th October 1971 he suggested the school “establish a unit of its own which might undertake analytical work on ceramics and metals… such a unit should also include facilities for the study and identification of those organic remains which it is now so much de rigueur for excavators to preserve and report on.” This letter lays out Hector’s intentions clearly and the immediacy of it shows how important this project was to him.

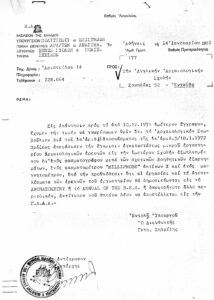

Permission is granted for the establishment of a laboratory within an existing building in the grounds of the BSA. (BSA Corporate Records, Athens, Fitch Laboratory)

Soon after this, Hector wrote the first formal proposal for a ‘Mini-Lab’ that was distributed to the BSA Managing Committee. In it, he states that this laboratory would bring archaeologists and scientists under one roof and that “the school would lose nothing by being seen to be a pioneer in a direction where others will surely follow.” A vision that history has proved quite accurate. The Mini-Lab proposal was largely well received, though numerous individuals raised issues over how money would be raised[5] and that the costs had been underestimated. Others raise issues of the laboratory being isolated and suggest instead that the BSA collaborates with other laboratories in the UK and Greece, and others go further and indicate they do not fully support the idea of science-based archaeology, saying that:

“I myself retain reservations about the scheme, though in doing so I am probably putting myself on the shelf in an age where archaeology is becoming increasingly science-based. I only hope that Catling has not started a fashion”.

Luckily, with a vote of 9 in favour and 3 against, most of the Managing Committee were in full support of the Mini-Lab project and soon planning, with guidance from Teddy Hall and Martin Aitken, began. Letters and proposals were sent to the Archaeological Service in Greece for permission to set up such a project, and on the 24th January 1972, permission was granted!

The next challenge, with a threat of this idea not being realised, was funding… more on this next week!

Bibliography

Catling, H.W. 1963. Minoan and Mycenaean pottery: composition and provenance. Archaeometry, 6.1: 1-9.

Catling, H.W., Richards, E.E., Blin-Stoyle, A.E. 1963. Correlations between compositions and provenance of Mycenaean and Minoan Pottery. The annual of the British School at Athens, 58: 94-115.

Catling, H.W. and Millett, A. 1965a. A study in the composition patterns of Mycenaean pictorial pottery from Cyprus. The annual of the British School at Athens, 60: 212-224.

Catling, H.W. and Millett, A., 1965b. A study of the inscribed stirrup‐jars from Thebes. Archaeometry, 8.1: 3-86.

Catling, H.W., and Millett, A. 1965c. A study of the inscribed stirrup‐jars from Thebes.” Archaeometry 8.1: 3-86

Catling, H.W. and Jones, R.E., 1977. A reinvestigation of the provenance of the inscribed stirrup jars found at Thebes. Archaeometry, 19.2: 137-146.

Catling, H.W., Cherry, J.F., Jones R.E., and Killen J.T. 1980. The Linear B inscribed stirrup jars and west Crete. The annual of the British School at Athens 75: 49-113

Catling, H.W. 2005. The birth of the fitch laboratory. The annual of the British School at Athens, 100: 407-409

Keane, K. 2022. Consumer price inflation, historical estimates and recent trends, UK: 1950-2022. Office for National statistics.

Kiriatzi, E. 2022. The Marc and Ismene Fitch laboratory: μίσος αιώνας διεπιστημονικές αρχαιολογικής έρευνας. Archaiologia 139: 86-97

Footnotes

[1] Hector Catling, prior to becoming BSA director in 1971, was the Assistant Keeper, and subsequently Senior Assistant Keeper, in the Department of Antiquities of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (1959-1971). It was during his time in Oxford that Hector first became acquainted with the Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art (RLAHA) and its director Edward Teddy Hall and other staff including Martin Aitken and Anne Millett.

[2] Edward ‘Teddy’ Hall was Director (1954-1989) of the newly founded Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art (RLAHA) at the University of Oxford. Prior to this he completed his PhD thesis on “The development of an x-ray fluorescence spectrometer for non-destructive analysis of archaeological materials”.

[3] Martin Aitken worked at RLAHA from 1957, he contributed to the development of radiocarbon dating, developed the proton magnetometer and Squid magnetometer. In the 1960s, he moved to thermoluminescence dating and also developed optically stimulated luminescence dating.

[4] Vincent Robin d’Arba Desborough was the Chairman of the British School at Athens Managing Committee between 1914-1978.

[5] At time it appears from the correspondence in the BSA corporate records, that the British Government were not funding schemes like these because science-based archaeology was new and it had not been presented to them yet. A ‘May meeting’ is referred to in letters of 1972 that suggest a committee was forming to do just this, but until then, the British Academy was not able to offer financial assistance. Furthermore, in the early 1970s the UK was seeing skyrocketing inflation rates (Keane 2022, 3) and this appears to have also been an issue for some potential donors.

By Carlotta Gardner, Fitch 2024 Research and Outreach Officer